Steve Bartkowski arrived in New York, went to his hotel room and waited. Intimidated not by what was going to happen in mere hours but by the city of New York, Bartkowski didn’t want to get lost or mess anything up.

So he stayed put. The Cal quarterback was about to become the No. 1 overall pick in the 1975 NFL draft and unlike today, where tens of players and their families wait in green rooms to hear their names called and proceed to hug or fist-bump commissioner Roger Goodell, Bartkowski was on this adventure solo.

This was Bartkowski in the back of a New York Hilton ballroom, waiting for his moment with then-NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle, not an arena full of fans.

“It was sort of like a dream. It was like one of those deals where it happens and you project yourself into it and it just doesn’t really seem real until you have a chance to get back and reflect on what just happened,” Bartkowski said. “One of those kinds of deals. Pete’s at the podium and he’s announcing me as the first pick in the NFL draft and it all kind of hits you at that point.

“You sort of get lost in the fantasy, so to speak.”

The fantasy emerged because of the Atlanta Falcons. A week before the draft, Atlanta traded with the Baltimore Colts to move from No. 3 to No. 1, also sending Baltimore Pro Bowl offensive lineman George Kunz.

What is now a commonplace maneuver in the NFL, a team swapping first-round picks (among other things) to trade up for a quarterback, was a much different scenario in the mid-1970s. The Atlanta-Baltimore deal would be the first trade centered around swapping first-round picks to move up to take a quarterback in the Super Bowl era.

This was a different time. The draft wasn’t the spectacle it is now. The massive industry of draft information for the public wasn’t invented. There was no NFL combine. No pro days. No months of waiting and guessing and poking and prodding. Teams went off the film they watched and conversations they had. If they saw the production they liked from a player they wanted, they often drafted him.

he 1974 NFL season ended with the Super Bowl on Jan. 12. The draft took place on Jan. 28-29, a Tuesday and Wednesday.

“It’s interesting when you think about this because there’s so much controversy regarding the fact that the scouting system hasn’t been complete this year or last year, right,” said agent Leigh Steinberg, who was hired to represent Bartkowski after the draft. “No combine. No in-person visits with players and all the rest of it. If you think about it, the draft in 1975, I think it was the last year it was this way, was in January.”

In some ways, this year’s draft might be a push back to that past. In 1974, Bartkowski had been college football’s leading passer with 2,580 yards. He was the only quarterback taken in the first two rounds of the 1975 draft. He was Atlanta’s target.

The trade was not met with universal praise. Prior to the draft, the Atlanta Journal wrote Baltimore general manager Joe Thomas displayed “a shrewd football mind” in making the deal while also landing a Pro Bowl offensive lineman. Thomas himself told the paper it was a trade he believed worked for both sides.

After the draft, Newsweek panned the Falcons’ decision, calling Thomas’ trade with Atlanta “one of the most devastating gambits” for feigning interest in taking Bartkowski to necessitate the move for Atlanta to trade up.

“Thomas gave up practically nothing,” Newsweek writer Peter Bonventre wrote. “But in return got All-Pro offensive tackle George Kunz. He then used his slot in the draft to pick North Carolina guard Ken Huff, whose progress should be worth watching.”

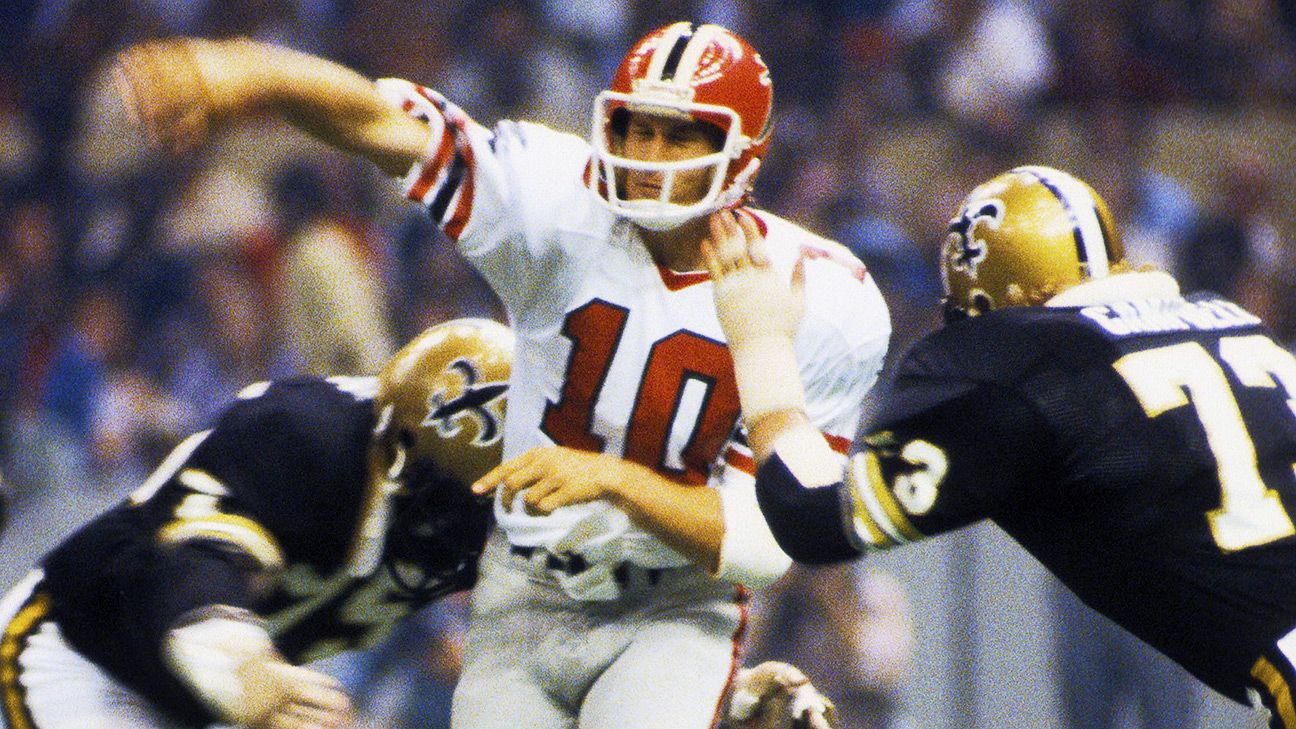

Bartkowski ended up playing 11 seasons in Atlanta, completing 56.2% of his passes for 23,470 yards, 154 touchdowns and 141 interceptions, making two Pro Bowls. The Falcons made the playoffs three times with Bartkowski as the starting quarterback.

Through Bartkowski’s senior year and then in the Hula Bowl and the Senior Bowl, he started to realize he might have a chance to be taken high. This was before the days of almost anything draft-related, so the only information he gathered was on his own, including seeing future Hall of Famers Randy White (No. 2, Dallas) and Walter Payton (No. 4, Chicago) play.

A week before the draft, a call came to a house Bartkowski rented with some college teammates in Orinda, California. Then-Falcons coach Marion Campbell was on the phone.

“He introduced himself. He told me a deal was in the works and they were going to trade for the number one spot and I was going to be their pick,” Bartkowski said. “It was a big night in Orinda. I can remember that. We had a pretty neat celebration that night.”

Campbell and Bartkowski spoke for about 10 minutes. Then, Bartkowski called his parents. He wanted them to hear the news first – or at least first after his roommates. He’d also have to go to New York for the draft, the only player in attendance. He didn’t own a sport coat or a tie and didn’t want to look bad in front of Rozelle, so he “piece-mealed some stuff together” to get ready.

“The only thing I regret not doing was not getting a haircut,” Bartkowski said. “I don’t know if you’ve seen any of those draft pictures but I look like a hippie, but you know, was in the middle of the hippie culture out there in Berkeley, California.

“It was a unique experience.”

And one that’s totally different today from now, where the draft is an event and trading up to take a quarterback is almost a yearly tradition.