Michael Jordan shuffled papers as he sat overlooking the basketball court on the Charlotte Bobcats sideline. It was March 2010, and the five-time NBA MVP was awaiting a final decision on league approval for him to be a majority owner of the Bobcats. As a camera panned down, you could see that his black leather-heeled boots landed well above the ankle. They paired with wide-leg jeans frayed at the bottom and a penny-brown corduroy blazer with epaulets and elbow patches.

An image of Jordan in his Chelsea-style boots, commonly referred to on social media as “brunch boots” because of their popularity among men who get decked out to ingest a carafe of mimosas with a side of waffles on the weekends, littered sports television shows, blogs and newspaper sections the next morning. At that moment, I knew this childhood idol, who once defined my understanding of cool — a man who famously sourced cotton from Egypt for custom dress shirts — would henceforward be sartorially categorized with middle-aged father figures, the neighbor who waters the lawn at 6 on a Saturday morning and every AP Calculus teacher ever.

With time, Jordan, now 57, leaned in further than Sheryl Sandberg to this retirement aesthetic. He fully embraced dad jeans, Canadian tuxedos, billowing golf shorts and boat-sized pant legs. I cringed with each meme poking fun at his wardrobe and every mention of his ongoing style dive.

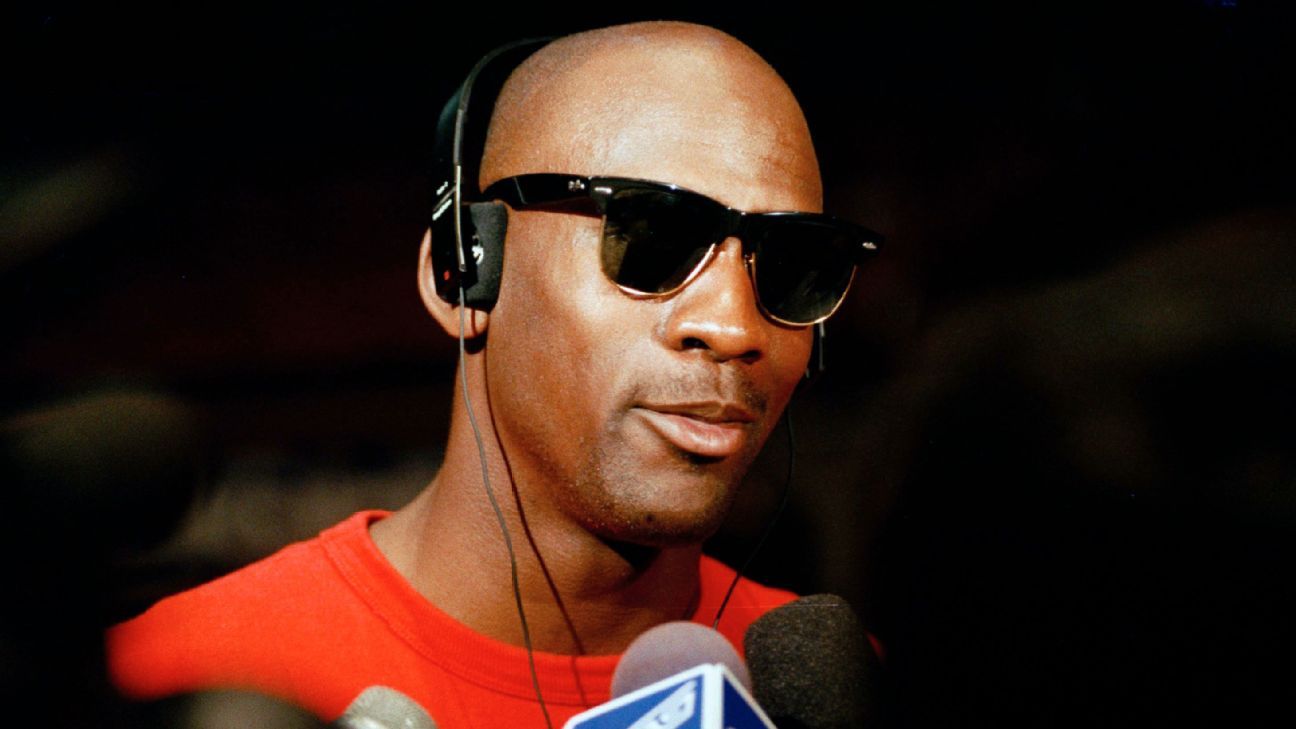

“The Last Dance,” a 10-part series that explores the Bulls’ dynasty through the lens of the 1997-98 season and that will be available on Netflix starting Sunday after a run on ESPN and ABC, served as a reminder of his style icon status. This is a man who turned male-pattern baldness into a shiny aerodynamic masterpiece. The most popular sneaker of all time was branded in his likeness. Jordan made a pirate accessory a must-have item and wore a beret better than Claude Monet. His superstitions helped change the length of NBA regulation basketball shorts.

“His economy of movement was always extraordinary. He wasn’t a player who was flinging himself around all over the place,” Vanessa Friedman, fashion director at The New York Times, said of Jordan. “His dressing is the same. It has that sort of economy of choice, ‘I’m going to have one earring that’s going to look like this. I’m going shave my head, and it will look like this.'”

How could a man with the highest points-per-game average of all time in the regular season and in the playoffs, who was known to be obsessive about greatness — extending to his wardrobe, branding and stats — shed his cool? I didn’t want this to be a part of his legacy. I had questions that Jordan’s boots would never dare to answer, but maybe a revisit of his closet past could provide some insight.

How did sneakers, shorts and two gold chains forever change the game?

The 1984 draft was the start of Jordan’s public style narrative. The former University of North Carolina guard, who left for the draft a year before his scheduled graduation, entered the Felt Forum at Madison Square Garden in a pinstriped suit, cropped hair and a simple tie. The North Carolina native — and the No. 3 pick that year (Akeem Olajuwon, who became Hakeem Olajuwon in 1991, was No. 1) — presented as the kid next door, the college student out on his first job interview as he held up his No. 23 Bulls jersey. It was like dangling dollar bills in front of eager marketers. Jordan signed with Nike in his rookie year.

Jordan debuted the prototype Nike Air Jordan sneaker during a preseason game in ’84. The shoe was a black-and-red colorway of the Nike Air Ship silhouette, which he wore while awaiting his signature sneaker. That shoe drew a warning from the league. The same colorway of the actual Air Jordan was banned for the regular season. The NBA mandated that players wear shoes that not only matched their uniforms but matched the shoes worn by their teammates. That policy led to the “51 percent rule” — shoes had to be majority white and in accordance with what the rest of the team was wearing. Jordan continued to violate the rule. It was widely rumored that MJ had been hit with a $5,000 fine for violating the rule. ESPN previously reported that there was no evidence that Nike ever paid a fine.

Jordan went on to wear his banned shoe in the 1985 All-Star dunk contest, where he topped off the look with two gold chains that flew through the air as he released the ball through the hoop. The cachet of being banned spoke to the swagger and bravado of hip-hop fashion. It gave Jordan a little edge and helped evolve his backstory and brand. The ban went on to become a promotion for Nike. The television spot’s voice-over noted, “On Sept. 15, Nike created a revolutionary new basketball shoe. On Oct. 18, the NBA threw them out of the league.”

“At the time, the NBA tried their best to keep hair and what the players wore from head to toe as uniform as possible,” said Jeff Staple, founder/CEO of RAD and designer of the famed Nike SB Dunk “NYC Pigeon” sneaker. “But that rebellious influence of hip-hop is there.”

And the chain might have also been a subtle jab at his opponents, Staple suggested. “Jordan walks onto a court, and you — as a competitor — see him with two gold chains that he doesn’t care if it gets ripped off. He’s so good that he knows it won’t happen.”

As reported on The Undefeated in 2018, Jordan wore his UNC practice shorts under his Bulls uniform for every game in his early days. To accommodate the extra “layer of luck,” Jordan asked for longer game shorts, which were a few inches above the knee in the early-to-mid-’80s, so the blue and white didn’t peek out from under the red, black and white. MJ’s longer and loose-fitting shorts caught on. The NBA gave the regulation shorts a little more legroom from then on. And when Mars Blackmon (Spike Lee) asked Jordan in another Nike ad whether it was “the shoes” and “the extra-long shorts” that made him great, the baggy basketball shorts moved beyond the court to a men’s streetwear staple.

“Michael in those tiny shorts, his swag doesn’t even fit in those,” said Jermaine Hall, director of Medium Editorial Group, who previously held executive editorial posts at Vibe, XXL and BET. “Mike gets a bad rap now based on how he dresses. But Michael in his prime was a fashion-forward dude, both on and off the court.”

The baggier and balder, the better?

Jordan racked up endorsement deals with Hanes, Gatorade and Upper Deck, among others. His image became a multimillion-dollar business. (He’s now a billionaire.) His attire reflected the shift from star player to one of the most marketed images on the planet. In the early ’90s, Jordan transitioned out of the walk-up warm-up T-shirts and pants. Suiting became his off-court armor.

According to GQ magazine, Chicago tailor Alfonso Burdi created a suit prototype for Jordan that included “baggy pants, jackets extra long and extra full.” Burdi had planned to adjust the suit to a traditional slimmer cut upon fittings. Jordan preferred the loose look. The NBA All-Star ordered more than a dozen of the style. This became his power suit. While the ’80s favored volume, like exaggerated shoulder pads, the ’90s ushered in minimalist suiting with breathable fabrics that moved in unison with the body. It’s as if Jordan combined both eras to project his desired image. It would be baggy like the shorts he wore on the court, with shoulder pads to provide his slender frame an illusion of width.

“When Jordan started wearing loose-fitting suits, they were immaculate. Every crease was crisp and wrinkles escaped,” Friedman said. “He was always impeccable and calculated. In the same way that he was utterly calm when he was playing, completely in control and dominant, his clothing said the same thing.

“If his suits were oversized, they were oversized for a reason. The line of his jackets was perfect. [His look] was incredibly consistent, and it all had integrity.”

Giorgio Armani’s menswear collections of the late ’80s and early ’90s are widely credited for creating a new interpretation of the suit. Armani thought the standard suit of that time stifled the body. He wanted to create movement and comfort, which made sense for a pro athlete. This influenced menswear designers around the globe. Many pro athletes employed tailors and garment makers to personalize the look for their frames. But why weren’t Jordan and other top athletes of the era front row at the international fashion week presentations and donning garments as soon as they graced the runway, just as Russell Westbrook and Dwyane Wade have done in recent years?

“The disconnect was there were not people like me or Rachel Johnson [LeBron James‘ stylist who also has worked with other notable athletes such as former NFL player and current ESPN analyst Victor Cruz] there to educate the fashion houses,” said Calyann Barnett, a wardrobe stylist and creative director whose client list includes Wade, Usain Bolt, Zion Williamson and Donovan Mitchell. “We had to explain to these houses, which most of them are based in Europe … we had to translate how the clothes they design for stick-thin models would work on men who are over 6-foot-6 and muscular.

“There wasn’t a line of communication during [Jordan’s era]. When stylists really came into play [in the early 2000s], we explained, ‘These are the people who will look great in your clothes and sell them.'” (Jordan did employ the services of designers, tailors and branding managers but did not have a full-time stylist. He worked with stylists on photo shoots.)

Regardless of whose name was on the garment — be it his trusted tailor or a Milan-based designer, Jordan became a master of power suiting. So much so that he had Nike designer Tinker Hatfield, who designed many of his Air Jordan sneakers, make the Air Jordan “Concord” XI, which was released in 1995, more formal. The sneaker featured a patent trim, which mimicked a pair of spats. Wearing the sneakers with a suit would work just as well as wearing them with his uniform.

To afford my first pair of Air Jordans in the late 1990s, I’d pocket about $3.75 of the $5 my mother handed me for lunch money each day. For two months, I ate 50-cent Linden’s Butter Crunch Cookies and 75-cent soggy fries, the cheapest combo of eats in my high school cafeteria that would stave off hunger until I returned home for dinner. The Concords were about $120 in my size after taxes, and I knew my mother would never want to spend that much on gym shoes. As I opened the black-and-silver box, I recalled His Airness soaring above the court at the United Center with these patent-leather-trim wonders on his feet as he clinched his fourth ring in Game 6 of the 1996 NBA Finals. The sneaker brought a piece of Jordan’s talent, style and showmanship to my then-15-year-old self. Decades have passed and trends have changed, but the sneakers, the stats and his overall image still represent that greatness.

Jordan’s style innovation extended beyond suiting and sneakers. His bald head, which he shaved clean in 1989 after managing a receding hairline, was a thing of beauty. Others, like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, had done it. But no one owned the branding of bald head quite like MJ.

“Previous to Jordan, we saw players like Dominique Wilkins and Karl Malone rock fades,” Staple said. “Jordan’s baldy felt streamlined and efficient.”

“When Chris Webber did it in Michigan, that was a style choice,” Hall said. “For Michael, it was done out of necessity. And it gave him a branded look that was very safe and approachable to everyone.”

There was also the gold hoop earring that dangled from Jordan’s left earlobe. The jewel made its debut in the mid-’90s and lives on today. He had dropped the two chains in favor of an understated interpretation of bling. While athletes and celebrities were weighing themselves down with gold chains and diamond-encrusted watches, a stereotypical purchasing habit of the newly monied, Jordan opted for a delicate hoop. Again, it was clean and steered clear of the stereotype, making it easily digestible to mass audiences who might have seen anything more as gauche.

At the 1996 Hollywood premiere of “Space Jam,” Jordan wore a gray suit, the jacket grazing his knees as he walked. A collarless buttoned shirt lay flat underneath, and his pant leg spilled over onto his black shoes. Jordan’s head shined, and the hoop earring twinkled. This was a man who looked as if he could carry your team to glory and play one-on-one with Bugs Bunny. And surely, that was done with intention. None of it was left to chance.

Did the brunch boot help turn the myth into a man?

Jordan won at everything — basketball, branding and style. He was the standard because he fought to be so. And that fight can be a young man’s game. The heeled boots, the endless pockets on his cargo shorts and his Easter-ready golf ensembles triggered a yearning for the Jordan of yesteryear. Jordan comfortably moved on from being the standard of cool, and we weren’t prepared to accept that. Our childhood heroes have the right to evolve. We have to accept that they aren’t just symbols of our youthful ideals but fully formed humans.

Jordan is the GOAT of GOATs, but his success is no longer directly associated with his physical appearance. He has grown beyond that. The Jordan brand will be forever revered regardless of what the man himself wears on the sideline or anywhere else. He’s aware that he’s a meme and has publicly gotten in on the joke. He knows that you’ve crudely critiqued his dadcore wardrobe. But will you still buy his shoes? Stream the docuseries about his greatness? Of course you will. And he knows that too.

“MJ is comfortable in his skin and with the style that he’s in,” Hall said. “It would take a quick phone call to revamp himself to what would look cool in 2020. I don’t think he cares. I think he’s fine.”

Jordan flirted in the 1990s with the wide-leg pants and washed-out jeans that he’s partial to now. The trends changed; his taste didn’t. Like many of us, he likes what he likes and sticks with it. He’s entitled to peer over his iPad, as he did in the docuseries, to poke fun at Scott Burrell while wearing khaki shorts. There’s a Zen-like beauty to this level of self-acceptance.

“This is a part of his messaging: ‘I’m not going to change who I am because the times have changed, and you’re just going to accept it,'” Barnett said. “It’s a boss mood.”

“The Last Dance” serves as a reminder that Jordan expected nothing less than greatness from himself and his teammates. It solidified him as this godlike figure for a new generation of fans. The series also provided us the space to embrace the Jordan of then and now at the same time. It humanized him. It made our idol feel real. And he has earned the right to be here, dad jeans and all.