This story was originally published on August 14.

Prior to his death in 2005, Hunter S. Thompson, a foremost chronicler of America’s last 50 years, once wrote the following for ESPN:

“We must have football. What would this country be without football in October?”

Thompson’s assessment of American culture isn’t wrong.

The sport’s influence and power have led the NFL to touch almost every part of life: TV, politics, food, gaming, business, fashion and on and on. And it took 100 years to get there.

History usually requires a long lens to truly assess empires and influence, but as pro football in this country reaches the century mark, it has grown and expanded along with America. When factories ruled the Midwest landscape, pro football came, too. When Americans moved to the West and Baby Boomers spurred the economy, football grew and reaped many of those same benefits. When cities like Atlanta, Houston, Nashville and Seattle became major urban centers, the NFL expanded to include them. And as televisions arrived in most every home, the NFL gave viewers what would eventually be the year’s biggest television event: the Super Bowl.

How did the NFL take over the United States? Here’s where the NFL began and how it spread to every corner of the nation.

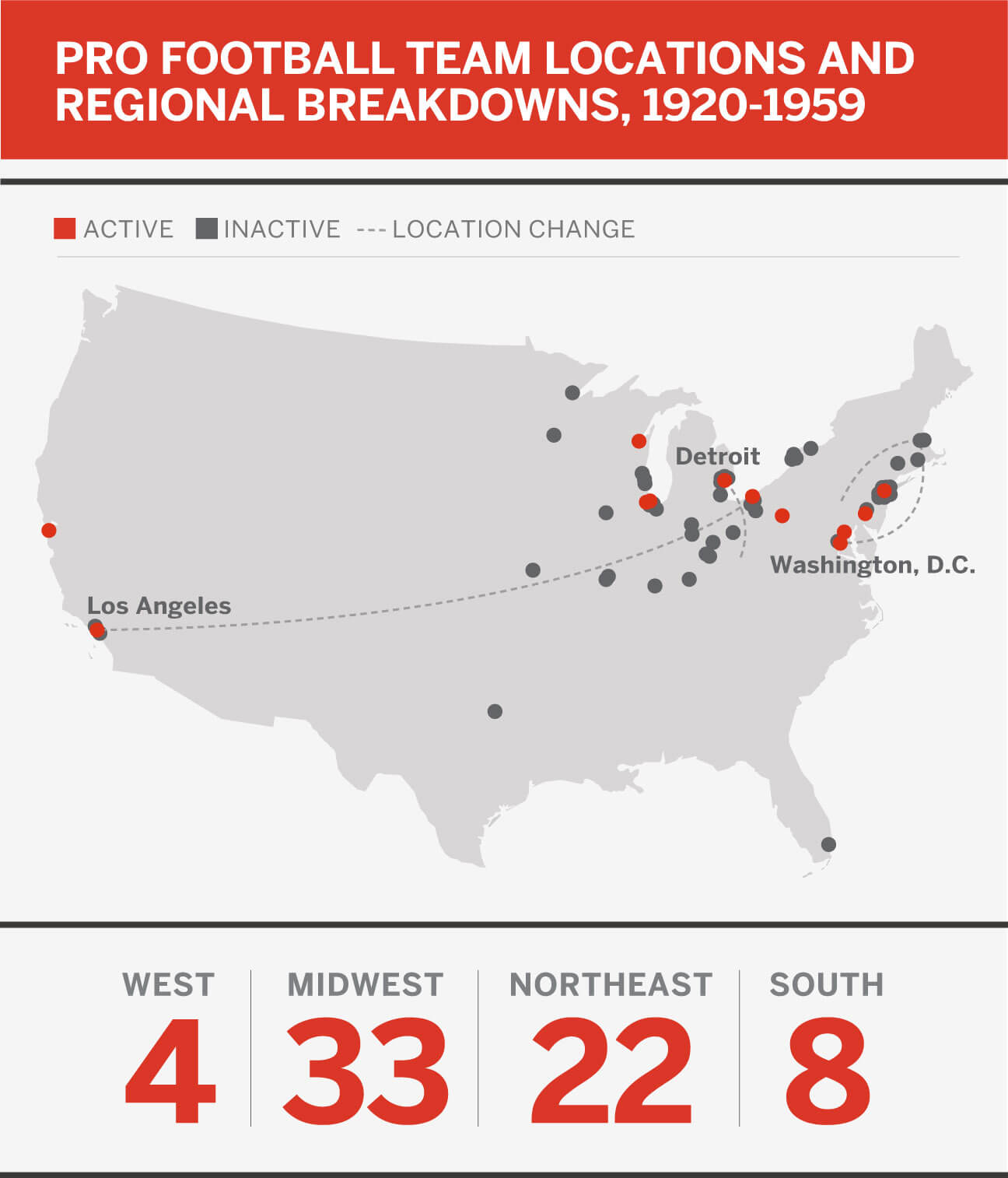

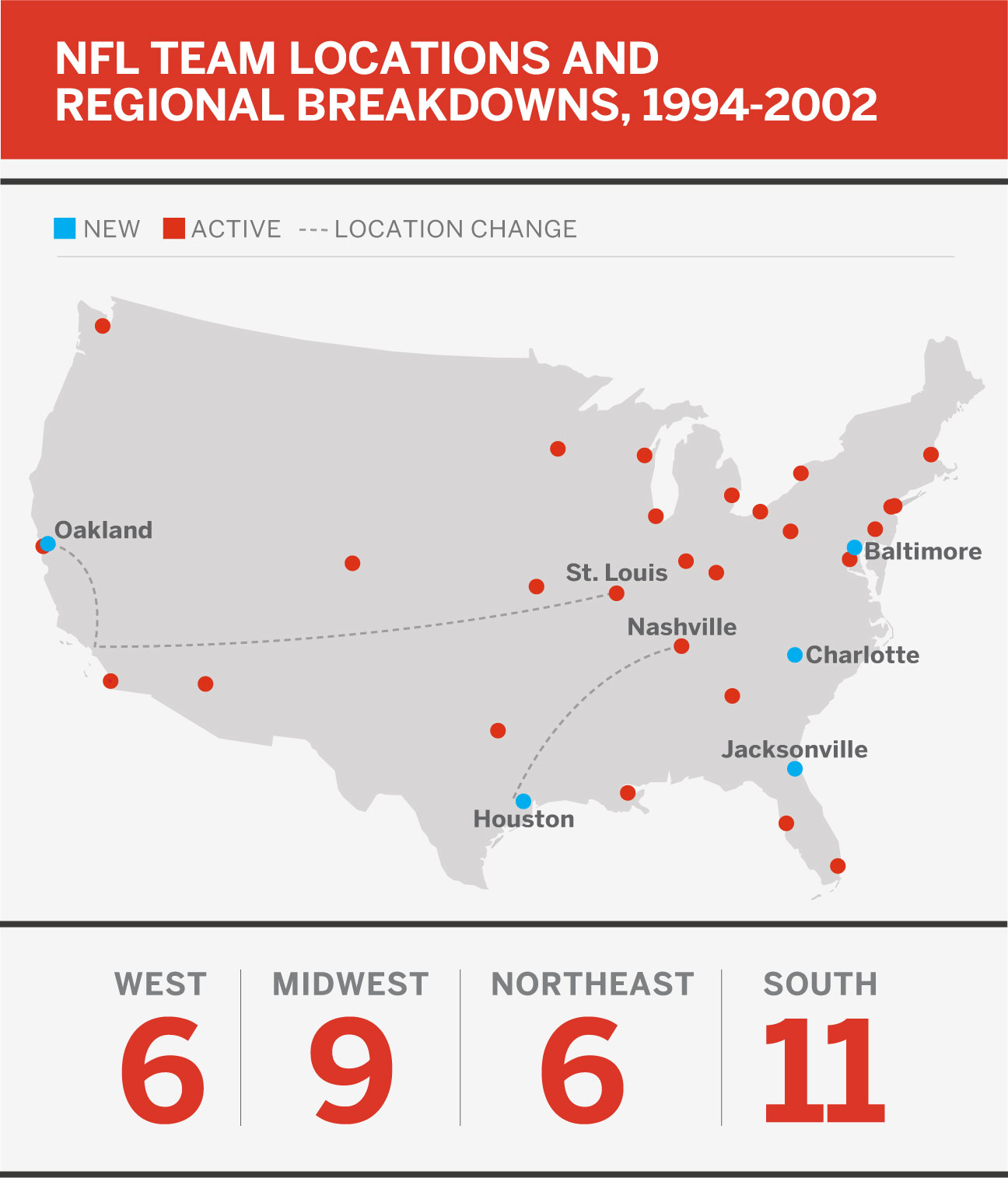

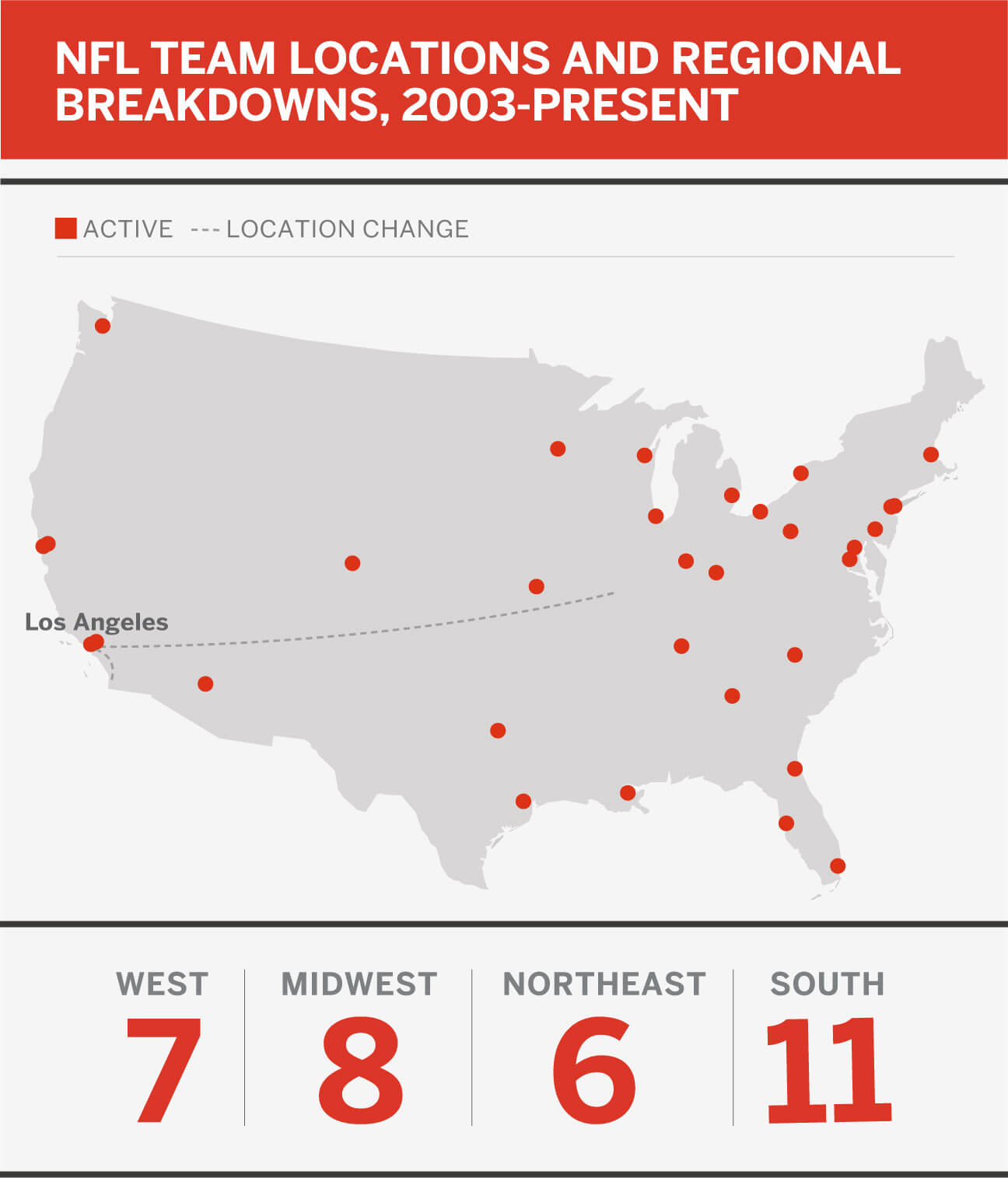

Regions assigned by U.S. Census Bureau demarcation.

Playing professional football 100 years ago did not come with the prestige, celebrity and prosperity synonymous with the stars who shape the modern game.

The NFL’s roots can be traced to the northeast corner of Ohio, where football was nothing more than a competitive outlet for college athletes who graduated into the working class — an activity organized and branded by athletic clubs sponsored by various employers.

From 1920 to 1930, 46 organizations came and went — a reflection of various companies trying to establish teams without significant financial stability. Even the league’s first champion, the Akron Pros, lasted only six years. You can stump trivia opponents by knowing the Tonawanda Kardex played a single game in 1921 before vanishing into football obscurity.

What wasn’t so different a century ago was the prominence of free agency and the importance of getting paid. The possibility of making football a profession, rather than a hobby, was realized after University of Illinois star Red Grange signed with the Chicago Bears — then known as the Decatur Staleys of the A.E. Staley food starch company — and toured the United States in 1925 to play other teams.

“Playing pro football or being associated with football wasn’t what it is today. People didn’t aspire to play professional football,” said Jon Kendle, the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s director of archives and information. “There wasn’t a lot of money in it until Red Grange signed to play with the Bears. The league’s expansion west can be attributed to that Red Grange tour.”

League president Joseph Carr recognized the need to limit the number of fledgling teams from small markets and directed the focus toward bigger cities. From 1930 to 1952, 14 franchises faltered, which was a significant decrease from the rampant turnover in the 1920s.

Baseball was America’s sport and it was no secret football tried to hitch itself to baseball’s rampant popularity. Football games were often played in baseball stadiums that could house bigger crowds with team names such as the New York Yanks and the Cleveland Indians.

Yet by 1953, the 12-team NFL was shaping into a league set to expand from its small corner of the country and positioned for exponential growth in the 1960s.

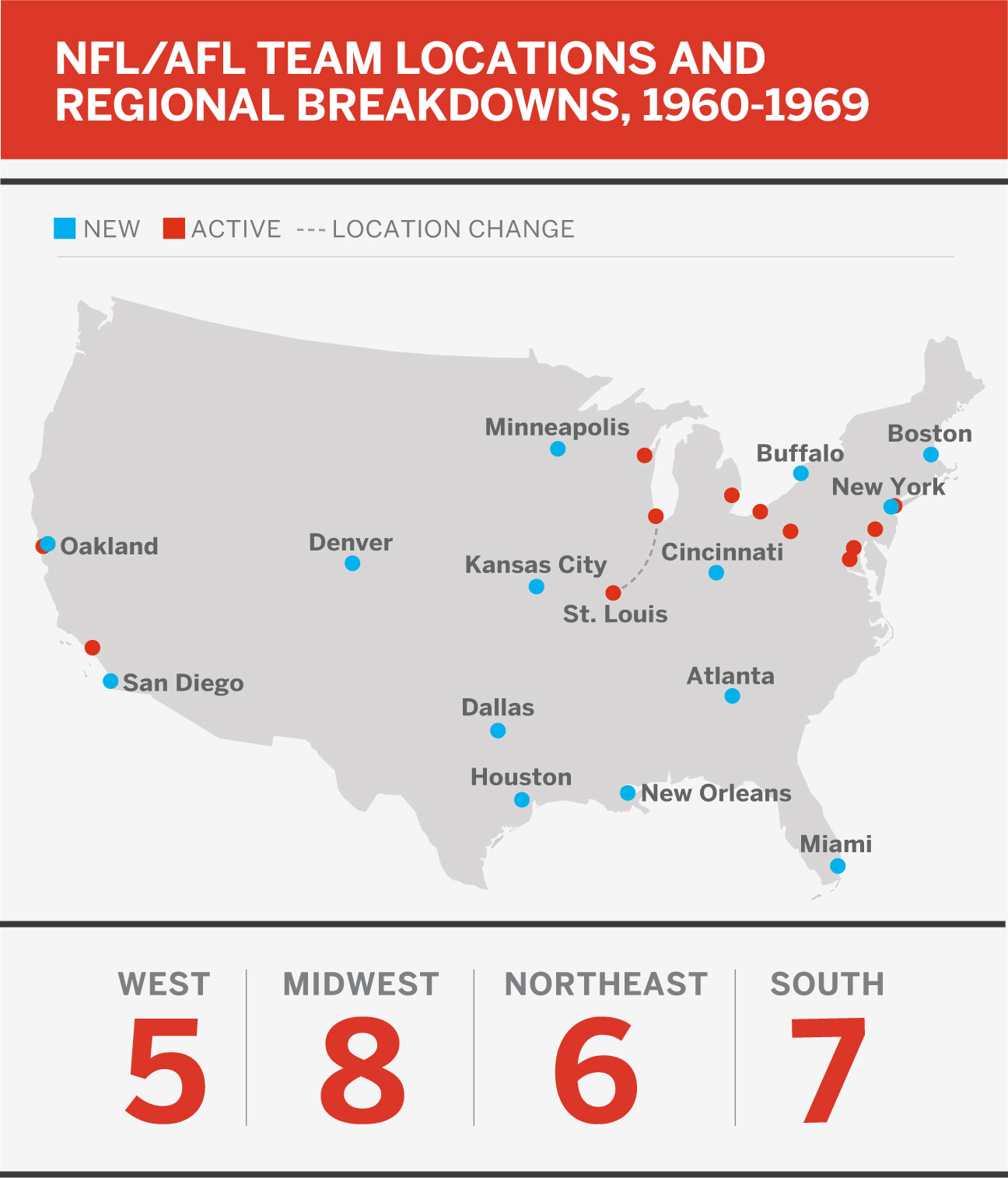

“The Merger” is the NFL’s watershed moment. The National Football League and American Football League agreed to merge in June 1966. The leagues maintained separate regular-season schedules for the next four seasons before coming together in the 1970 season to form one league with two conferences. The time period was more transformative to the league than any other and made the NFL the monopoly it is today.

The AFL, the only rival league to truly challenge the NFL, was founded in 1960. Partial owners such as Ralph Wilson Jr. and Lamar Hunt wanted NFL franchises, but the league was comfortable with the franchises in place at the time.

That collection of owners, dubbed “The Foolish Club” by their peers, ultimately succeeded, and the AFL began with more teams spread from coast to coast. With the Houston Oilers, Kansas City Chiefs, Denver Broncos, Oakland Raiders and Los Angeles Chargers, the league was more represented in the West. But the AFL also challenged the NFL in its own backyard, establishing the New York Titans (later Jets) and Boston Patriots.

In this decade, television was the NFL’s best friend and things really took off. More than half of the U.S. population had access to a TV and live entertainment came with it. The combination of a mega-deal with ABC, plus the financial backing power these owners already had, breathed life into the AFL. The decade saw the first televised presidential debate and, in January 1967, the first Super Bowl (then called the AFL-NFL Championship) and the first Super Bowl halftime show.

The AFL brought with it many things still prevalent in the current game: high-flying offenses, exclusive TV rights and star power, to name a few. To end the decade, the AFL’s New York Jets pulled off the game’s biggest upset, beating the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III with the league’s biggest star, Joe Namath, winning MVP.

If you’re wondering, a 30-second Super Bowl commercial cost $55,000.

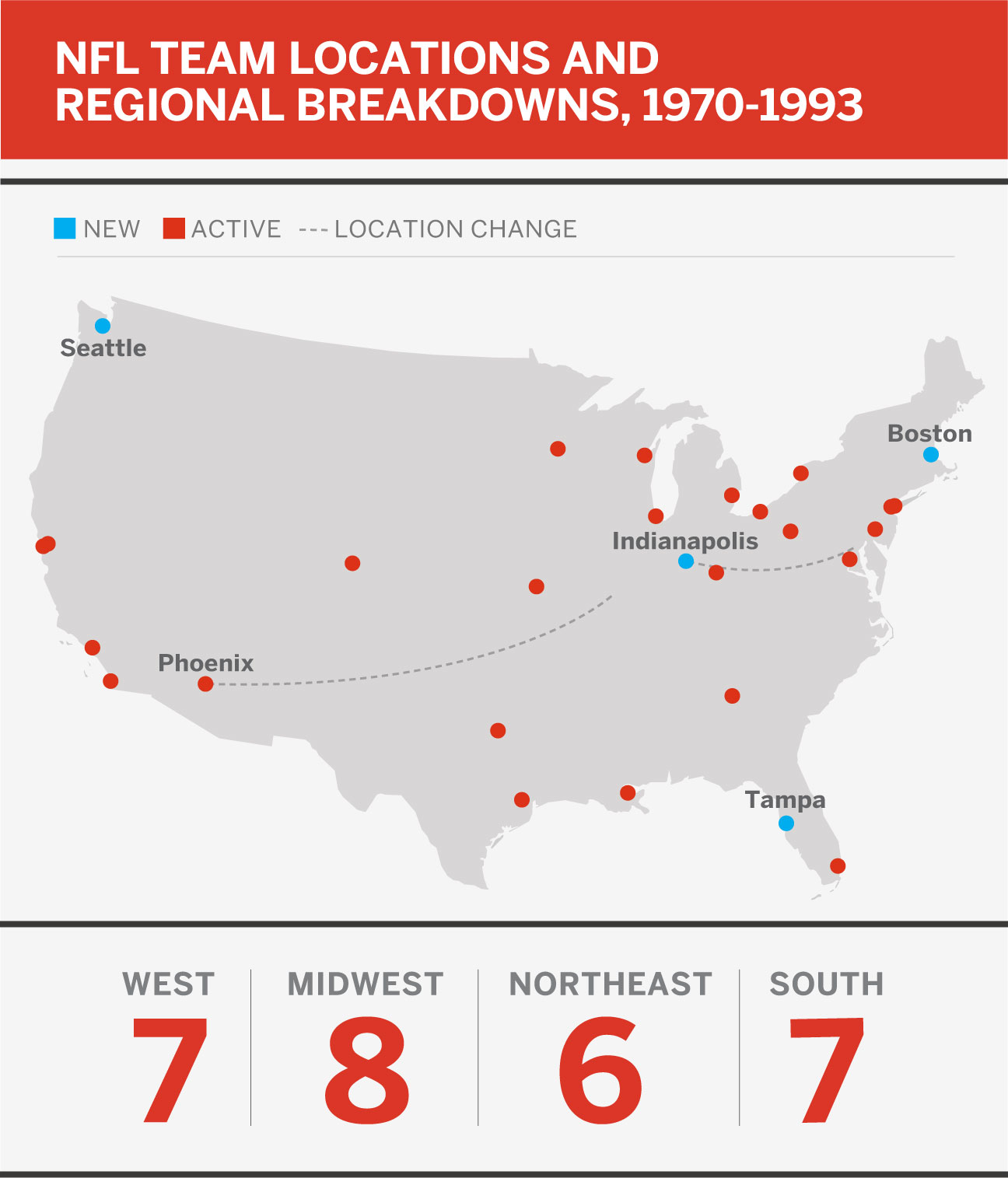

The momentum of the AFL-NFL merger carried pro football into a stabilizing period that saw little change through the 1970s and 1980s. Two teams were added in 1976 — the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and the Seattle Seahawks — and the markets in which they were created were significant. While the NFL had already been spreading West and into the South, it now had established posts at drastically opposite points of the country.

In the Buccaneers’ third season, they stunned the Philadelphia Eagles to win the franchise’s first playoff game. Doug Williams, who was the only black starting quarterback, was the star the Buccaneers badly needed when he debuted in 1978.

By this time, the NFL had 28 teams and revenue was blossoming. Players wanted their piece of the pie and, as a result, there were four lockouts from 1970 to 1987. The longest come in 1982 when the season was shortened to nine games. One lockout has occurred since, in 2011, imposed by owners after failure to come to an agreement on a collective bargaining agreement with players.

The NFL continued to chart new territory in the South with teams in Charlotte, North Carolina (Carolina Panthers), Nashville, Tennessee (Tennessee Titans), and Jacksonville, Florida (Jaguars) while restoring franchises to areas that had previously lost them.

It was an era filled with unprecedented moves, powered by the promise of stadiums funded by public money.

When Baltimore was ready to deliver, pro football returned to Maryland in 1996. Browns owner Art Modell moved his team to Baltimore and NFL operations were suspended in Cleveland until 1999. Modell rebranded to the Ravens and the Browns identity and franchise history remained part of Ohio.

“The end of the 1980s and into the ’90s, franchises moving, really all in my mind, they’re all related to the building of stadiums,” Kendle, of the Hall of Fame, said. “The Ravens coming into existence, Baltimore was ready to have another franchise after the Colts moved to Indianapolis. The city was willing to finance a stadium and you saw a lot of teams throw their hat in the ring, so to speak, whether they were serious about moving or leveraging the idea of moving to get new stadiums for themselves.”

During a similar timeline, the Houston Oilers left for Tennessee after failing to secure a new stadium in Texas. Football returned when the Texans were established in Houston in 2002.

Other teams and owners took notice of the changing landscape and saw an opportunity. In a seven-year period from 1995 to 2002, 14 new stadiums were built, including those for the Ravens’ rivals in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati.

As history repeats itself, the NFL in the new millennium is highlighted and scarred by the same themes and developments that were everywhere in its first 100 years.

Only now it’s amplified by more TV, social media, controversy and wattage of star power.

Until 2016, the NFL was incredibly steady. Monolithic stadiums were built. Player safety and free agency were always topics. The Patriots won.

The NFL went two decades without a team in Los Angeles, the second-largest TV market in the U.S., and wanted back in. The planets aligned when the Rams bolted from St. Louis to return to L.A., and the Chargers beat out the Raiders to join them. And they’ll have a shiny, futuristic stadium to share.

And here we are.

In 2020, the Raiders are planning to move to Las Vegas. The map of the NFL cities, if the league had its druthers, might have a decidedly international future.

The league began hosting international, regular-season games in 2005. So far, Mexico City, Toronto and London have hosted games. London has always been talked about as a presumptive international favorite to get a team. Pro football in Mexico has developed a strong fan base and the NFL has an office in Mexico City. The San Francisco 49ers are also in discussions for a game in China.

Beyond the hypothetical, the NFL has reached a bit of a crossroads. It is still incredibly popular. According to the league, 46 of the top 50 telecasts in 2018 were NFL games. Not just sporting events. NFL games were watched more than almost anything else on TV, no matter the network. Furthermore, commissioner Roger Goodell is targeting $25 billion in revenue by 2027. But injury and long-term health issues drive the perception of the league’s future. It also remains to be seen if international popularity goes beyond the novelty and revenue could be produced to sustain a home team away from the United States.

But now, the NFL owns every corner of the country. Where will the dots be on the next map of the NFL? Maybe we’ll have to wait another 100 years.