NBA commissioner Adam Silver had a lot to consider in the fall of 2014, when he sat down to write an op-ed that would pivot the league’s longstanding opposition to sports betting.

At the time, professional sports leagues, including the NBA, were getting into business with daily fantasy sports companies while at the same time suing New Jersey to prevent the state from authorizing traditional sports betting. In addition, the NBA, for decades, had stood with the NCAA, NFL, NHL and Major League Baseball in ardent opposition to expanding legal sports betting in the United States. Silver was getting ready to break ranks.

He worked on the op-ed at his Manhattan office and at home, sometimes calling advisors late at night with questions about specific phrases. He consulted with a team owner and league executives. He didn’t even know what outlet would publish it.

Early in the evening on Thursday, Nov. 13, 2014, Silver’s op-ed, titled “Legalize and Regulate Sports Betting,” was published on The New York Times website. It would become one of the Times’ most popular op-eds, and it began, “Betting on professional sports is currently illegal in most of the United States outside of Nevada. I believe we need a different approach.”

The entire article was brief, straightforward and, yet, extremely bold. Silver was the first acting commissioner of a major U.S. sports league to come out in support of legalized sports betting. In 437 words, he pivoted the NBA’s long-held public opposition to sports betting and ignited a discussion about a taboo subject for all professional leagues.

“I think it was ground-breaking,” Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban said of Silver’s op-ed in an email to ESPN. “Leagues for decades were hypocritical about gaming, pretending it doesn’t exist. Adam ended that hypocrisy.”

Measuring the impact Silver’s op-ed had in leading to the current landscape is difficult. It came at a very complex time. The day before it published, the NBA announced an exclusive deal with daily fantasy giant FanDuel, which included an equity stake in the company. And just three weeks earlier, in October, the NBA, along with the other major sports leagues and the NCAA, sued New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie for the second time in an effort to prevent the Garden State from allowing sports betting.

“The risk in doing what he did was great,” Ted Leonsis, owner of the Washington Wizards and Washington Capitals, told ESPN. “In hindsight, it was exactly the right thing at the right time.”

With or without the op-ed, change appeared to be on the horizon, albeit a distant horizon. Silver, as it turns out, was an agent of change who believed expanded legal sports betting was inevitable. He was right.

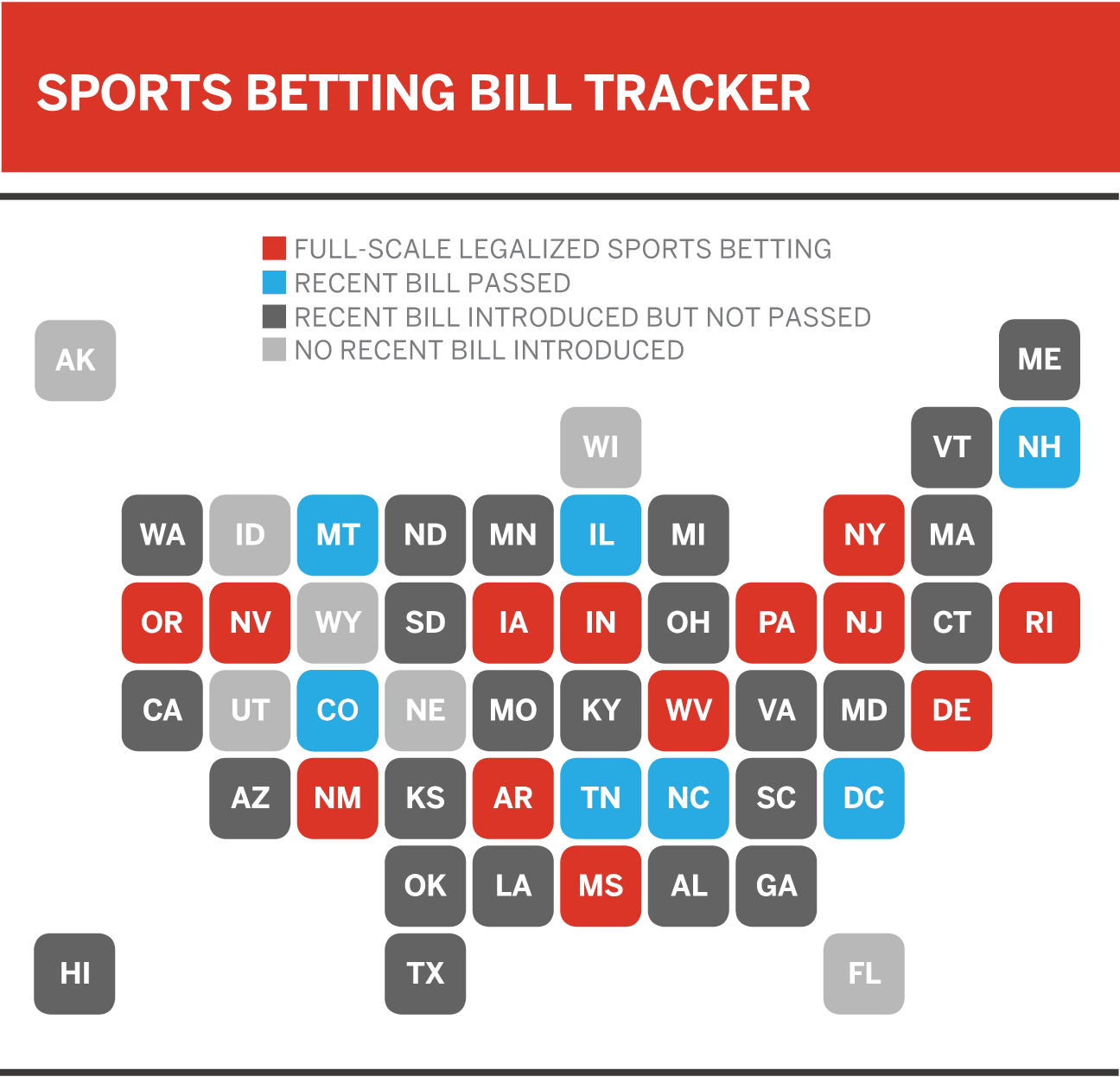

Five years after Silver’s op-ed, the federal prohibition on state-sponsored sports betting is gone, and legal sportsbooks are operating in a dozen states in addition to Nevada. Seven other states and the District of Columbia have passed sports betting legislation, and the NBA, NHL and Major League Baseball — after decades of adamant opposition to sports betting — have each partnered with U.S. sportsbooks. Even the NFL has done a deal with a bookmaker in Australia.

Year to date, the U.S.-regulated sports betting market has generated more than $600 million in taxable revenue for states.

‘Horse was about to leave the barn’

Silver received mixed reactions when he told the commissioners of the other leagues about his sports betting vision. Rob Manfred, after taking over as MLB commissioner in 2015, said that he agreed with many of Silver’s points in the op-ed and that sports betting deserved “fresh consideration.” But that tempered support was the best Silver received. The NFL and NHL remained adamantly opposed for the next three years, even as both leagues took steps to put franchises in Las Vegas.

Behind the scenes, though, the leagues were studying the issue, preparing for the day when more states would offer sports betting. Former NBA commissioner David Stern believes Silver’s op-ed had an enormous impact on the other leagues’ approaches to the issue and was very influential overall in the movement toward expanded legal sports betting.

“It indicated that the horse was about to leave the barn and it would be smart to jump on your own horse and follow along,” Stern said. “And they did.”

“It was critical,” added Cuban. “Prior, those in favor of gaming expected pro sports to fight back. With the hypocrisy gone, the legal steps could move forward.”

Others, however, thought Silver was being hypocritical by coming out in favor of legalized sports betting while the NBA remained in the suit against New Jersey. Silver countered those critics by saying a consistent federal framework for sports betting would be superior to a state-by-state approach like the one New Jersey was pursuing.

“Congress should adopt a federal framework that allows states to authorize betting on professional sports, subject to strict regulatory requirements and technological safeguards,” Silver wrote in the op-ed. “[W]ithout a comprehensive federal solution, state measures such as New Jersey’s recent initiative will be both unlawful and bad public policy.”

While Silver’s op-ed didn’t test the legal merits of the leagues’ lawsuit, the optics surrounding the case were definitely altered. Attorneys representing New Jersey mentioned the op-ed multiple times in briefs to make sure judges were aware.

“Judges live in the world, and they read the newspaper,” said Matt McGill, a partner at Gibson, Dunn & Crucher LLP, the first firm that represented New Jersey in the case. “It was important for us as proponents of sports betting to show the court that even the leagues themselves were not any longer saying that permitting New Jersey to engage in regulated, legalized, transparent sports betting would be the end of the world. They were perfectly prepared to accept widespread sports betting. They may indeed hope to profit on it.”

Attorney Ron Riccio, who represented the New Jersey Thoroughbred Horsemen’s Association in the sports betting case, cited Silver’s op-ed as an example of the leagues’ conflicted arguments. “I saw the Silver article as part of the leagues’ overall bad faith in arguing to the court that the spread of sports betting threatened the integrity of the leagues’ games on one hand,” Riccio told ESPN on Tuesday, “while, on the other hand, they were actively promoting the spread of sports betting. To me, the Silver article is emblematic of the leagues’ saying one thing to the courts under oath, while they’re doing the exact opposite to profit off the spread of sports betting.”

On May 14, 2018 — nearly six years after the case began — the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of New Jersey and struck down the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act of 1992, the federal statute that had restricted regulated sports betting to primarily Nevada.

McGill said that while it’s impossible to know how much, if any, impact Silver’s op-ed had on the final decision, it certainly didn’t hurt New Jersey’s case.

“I would go a step further and say it helped,” McGill said.

Regulated sports betting

Outside of New Jersey, sports betting was not a top priority for the gaming industry in 2014. The American Gaming Association (AGA), the Washington, D.C.-based group that represents the casino industry in the United States, didn’t even have a consensus position on sports betting.

“We were in a meeting … and someone said, ‘Wow, Silver just came out in favor of legalized sports betting,'” gaming industry consultant Sara Slane, a senior vice president with the AGA at the time, recalled. “I remember sitting there going, ‘What do we do?’ That really was the tipping point for the industry and the association that we really need to drive a consensus on sports betting.”

The AGA formed a sports betting task force in 2015, just months after Silver’s op-ed, and began building a lobbying coalition and coinciding strategy. The industry, with only a few defectors, came together and was soon all-in on sports betting.

“Commissioner Silver’s op-ed was very helpful in the fight to legalize sports betting. He persuasively made the case that legalized and regulated sports betting is better than the black market,” Joe Asher, CEO of William Hill U.S., said.

Leagues’ opposition disappears

As deputy commissioner, Silver spent time in international markets with legal sports betting. The experience shaped his views on the benefits of regulated sports betting. However, any consideration to changing the NBA’s position in the U.S. was put on hold in 2007 by a scandal involving ex-referee Tim Donaghy, who admitted to sharing information with gamblers and betting on NBA games, including ones he officiated.

Silver questioned why none of the NBA’s systems identified Donaghy’s scheme and thought there may be a better approach. Even Stern considered a future with expanded legal sports betting in the U.S., telling Sports Illustrated in 2009 that the league’s policy “was formulated at a time when gambling was far less widespread – even legally.”

Leonsis was on the forefront of the league’s shift on betting and was one of the owners Silver consulted with on the op-ed.

“My notion was what are we afraid of, when we know all this money is being spent offshore [with bookmakers] in an unregulated, untaxed and unmindful way?” Leonsis said in a phone interview Tuesday.

Today, the professional leagues’ opposition to sports betting has vanished. Their focus now is on how to monetize the growing regulated industry through data and fees based on the amount wagered on the games.

According to the AGA, there have been 60 commercial contracts between gaming operators and leagues, teams, arenas and stadiums since the Supreme Court ruling. Leonsis, with bookmaker William Hill, is building a physical sportsbook inside Capital One Arena in Washington, D.C., home of the Wizards and Capitals, and the Chicago Cubs also are considering putting a sportsbook at or near Wrigley Field.

In addition, the leagues are still holding out hope that Congress will pass federal sports betting legislation at some point instead of what Silver has called a “hodgepodge” of regulations that vary state by state. In the meantime, they’re cozying up to the gaming industry, mending fences after decades of keeping their distance.

“I’ve only been here since January,” said Bill Miller, president and CEO of the AGA, “but the receptivity that I’ve gotten from league owners, league commissioners and their offices has been very positive.”

When Miller looked back over Silver’s op-ed this week, he said one thing stood out.

“What he really was articulating [in the op-ed] was that times have changed,” Miller said.

ESPN contributor Ryan Rodenberg provided reporting in this article.