Last Monday in Chicago, San Antonio Spurs coach Gregg Popovich arrived at his pregame interview in the gloomy concourse of the United Center, the house that Michael Jordan built. So many of the league’s iconic highlights played out here in the 1990s, and those images seemed to be on Pop’s mind.

In response to a ho-hum question about the state of the Spurs, Pop took the chance to lament the aesthetic of the NBA in 2018.

“There’s no basketball anymore, there’s no beauty in it,” he said.

It was a startling statement from the best coach of the era, whose own championship team from just five seasons ago played arguably the most beautiful version of the sport we’ve ever seen.

Pop honed in: “Now you look at a stat sheet after a game and the first thing you look at is the 3s. If you made 3s and the other team didn’t, you win. You don’t even look at the rebounds or the turnovers or how much transition D was involved. You don’t even care.

“These days there’s such an emphasis on the 3 because it’s proven to be analytically correct.”

That’s the perfect choice of words — “analytically correct” — to connote the invisible algorithmic hand that now guides virtually all the action we see in NBA arenas. Front offices assign every part of the game bond ratings and credit scores. Financial terms such as efficiency, asset and value have infiltrated the discussion. Offensive tactics are homogenizing, while many tried-and-true forms of scoring fall by the wayside.

A prime example of what has been left behind: Carmelo Anthony, who is only by technicality still a member of the Houston Rockets.

The 2003 class

In June 2003, a group of amateurs including LeBron James, Dwyane Wade, Chris Bosh and Melo became professionals. Few draft classes can match such superstar clout, and over the past 15 seasons, those dudes have come to define the post-Jordan NBA.

That same month, Michael Lewis published “Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game.” Lewis, a former bond salesman on Wall Street, wove a dazzling narrative with a clear takeaway: The integration of financial reasoning, data and computation was bound to reshape pro sports forever. He was right.

At the time, the NBA was in an awkward spot. Every promising young player, from Vince Carter to Kobe Bryant, was labeled the next MJ.

Jordan rewired how we understand basketball greatness as he dominated in new and breathtaking ways. MJ’s most iconic moments featured him beating a defender off the bounce. He taught a generation that the path to the highest levels of hoops glory began with a dribble and culminated with heroic, unassisted buckets.

Jordan elevated pro hoops to new heights, but he did so via a virtuosic, isolationist aesthetic that tempted potential superstars into some bad habits. His approach was designed to overcome handsy defenses back when contact was the cornerstone of perimeter stifling. As with any iconic performer, his greatness was singular and suited to his own time.

The stars of the 2003 draft class got to meditate on MJ’s hero ball for years. But as the game changed, so did the league’s top young superstars — embracing ball movement, 3-point shooting and defensive versatility. Well, most of them.

It was clear from the jump that Anthony was special. I’ll always remember watching Melo’s 2003 Syracuse team upset Oklahoma in the regional final of the NCAA tournament. Carmelo was killing it, effortlessly blending speed, size, power, finesse and athleticism while putting up 20 points and 10 boards in beautiful ways I’d never seen integrated so well in college hoops. Fadeaways, post moves, dunks, putbacks and 3-pointers — the kid had it all, and he was using it to drive his team to the Final Four.

While many top prospects play with a raw, frenetic energy, Carmelo was cool. His poise stood out within the hectic, hyperactive setting of college basketball. Even in the national championship game versus Kansas, there was a knowing smoothness to his game. Rewatching that matchup, you’re struck by Melo’s easy smile as he puts up numbers in the biggest game of his life. It seems as if he’s playing a pickup game in front of 54,000 people at the Superdome.

Anthony was bound for glory. LeBron was going to be the first pick, but Anthony was a sure thing. His predraft analysis was glowing.

One particular scouting report from 2003 captured the essence of Anthony’s game in a nutshell: “[A] fluid player who shows great athleticism despite not having overly explosive leaping ability … [has an] innate feel for the game that most players have to develop.”

Simply put, Anthony looked like the most-skilled big man in a generational draft class, and he’d just shown his championship credentials on college basketball’s biggest stage. The scouts had difficulty homing in on any major weaknesses, but there were a few minor concerns at the time, such as in this assessment:

“He needs to improve on his perimeter defense such as lateral quickness and footwork. … Anthony at times can be such a dominant scorer that he can freeze teammates out of a game.”

This would metastasize over time. As the NBA slowly walked away from hero ball, Anthony’s shortcomings eventually snowballed into dealbreakers.

Melo in limbo

It’s unclear where Melo will get another chance to play NBA basketball, which seems crazy for a healthy 10-time All-Star who is just 34.

The problem: Anthony embraces an analytically incorrect style. He never updated his system. Like a kid playing Sega Genesis in the time of Red Dead Redemption, his game is woefully out of date. This fact became abundantly clear in the first round of the 2018 Western Conference playoffs between the Oklahoma City Thunder and Utah Jazz.

Look at the second half of Game 5. Anthony and the Thunder were down 3-1 in the series, trying to save their season. After Jae Crowder hit a 3 in Anthony’s face early in the third quarter, the Thunder found themselves down 25. Russell Westbrook drained two quick 3s and cut the lead. The Jazz called timeout, and Billy Donovan subbed out Anthony for Jerami Grant. Seven minutes later, Melo was still on the bench, and the Thunder had roared back, tying the score to start the fourth.

ESPN’s Royce Young described the scene on the bench: “[Melo] was seen begging assistant Mo Cheeks to come back in, and finally got his wish with 7:58 left in the fourth.”

But after the Jazz targeted Anthony on a pick-and-roll that ended with Donovan Mitchell torching Anthony on a basic switch, Donovan had no choice. He again pulled Anthony in favor of Grant, who played crunch time for the Thunder as they held on to win by eight.

Buckle �� pic.twitter.com/2k2gJ4MRJy

– Utah Jazz (@utahjazz) April 26, 2018

That Mitchell layup embodies a key weakness in Anthony’s portfolio. When he entered the league, hand-checking and physicality could’ve kept players like Mitchell at bay. But those days are gone, and now bigs are not only forbidden from camping out under the basket, they are also expected to keep up stride for stride with guards.

If brutal sequences like that suggested the Thunder might be better off without Anthony, this on/off data from the Jazz series proved it:

• In 194 minutes with Anthony on the court, the Jazz outscored the Thunder by 58 points and the Thunder had a net rating of minus-12.6.

• In the 94 minutes with Anthony on the bench, the Thunder outscored the Jazz by 32 points and had a net rating of plus-18.1.

Those splits paint a drastic picture. But here’s a more drastic fact: After dumping Melo in an offseason transaction, the 2018-19 Thunder suddenly have the most efficient defense in the NBA.

Advanced stats have never been kind to Melo on D, but what about on offense? After all, he was one of the most gifted young scorers of his era. Welp, those stats are also unkind.

For individual scorers, perhaps no statistic is as revealing as true shooting percentage (TS%), which measures a player’s overall efficiency while taking into account the added value of 3-pointers as well as free throws. Even in his best years, Melo excelled at beautiful and difficult shot types that are now largely frowned upon. He was good from dumb spots. He was great at the wrong thing at the wrong time.

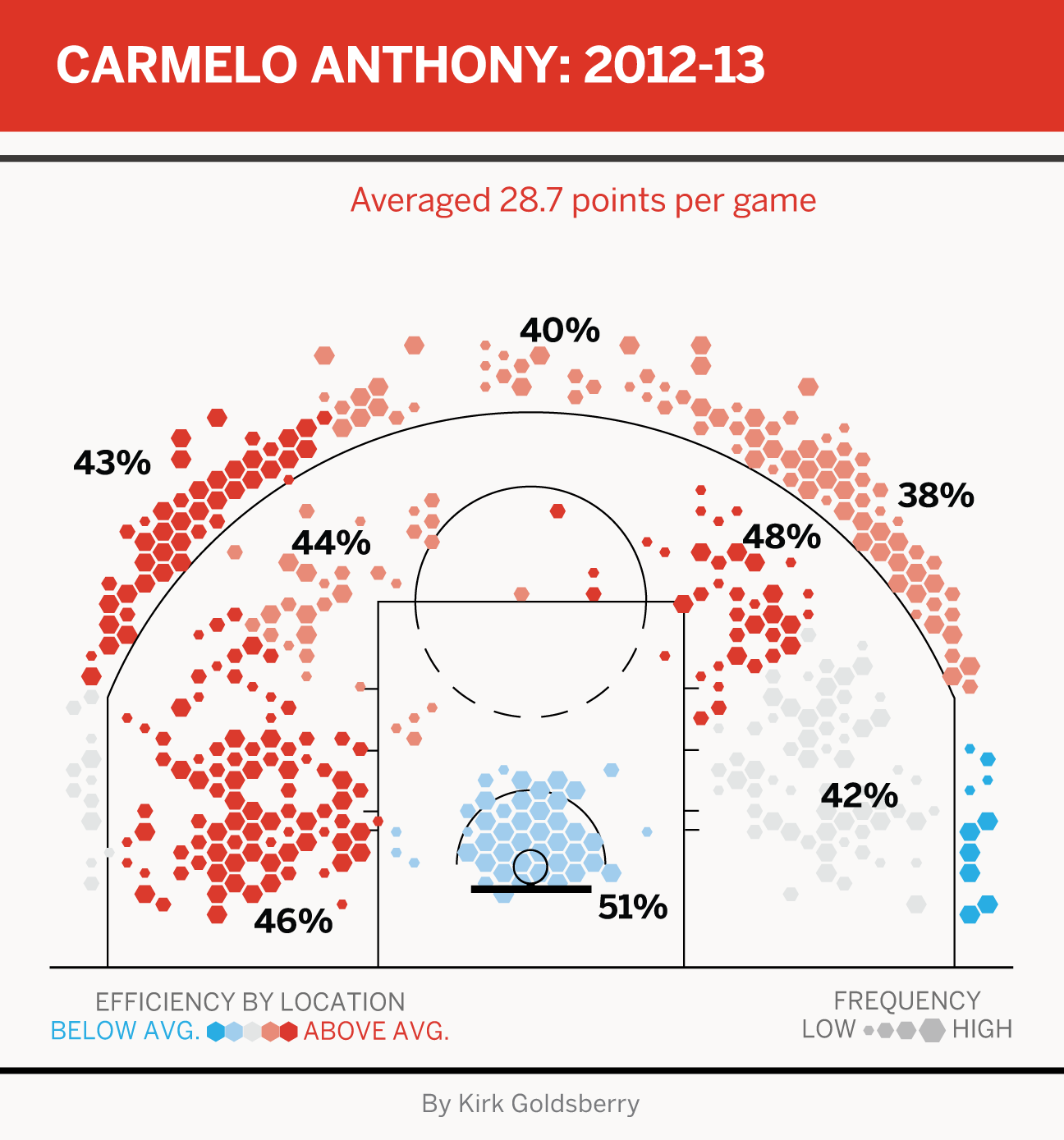

This shot chart from his 2012-13 scoring-title season shows a player who loves midrange scoring:

Anthony’s career TS% is 54.2, below the current NBA average of 55.7. His best season through this lens was 2007-08, when he logged a healthy 56.8 mark. However, even that number is paltry compared to that of other superstars and fellow members of his vaunted draft cohort.

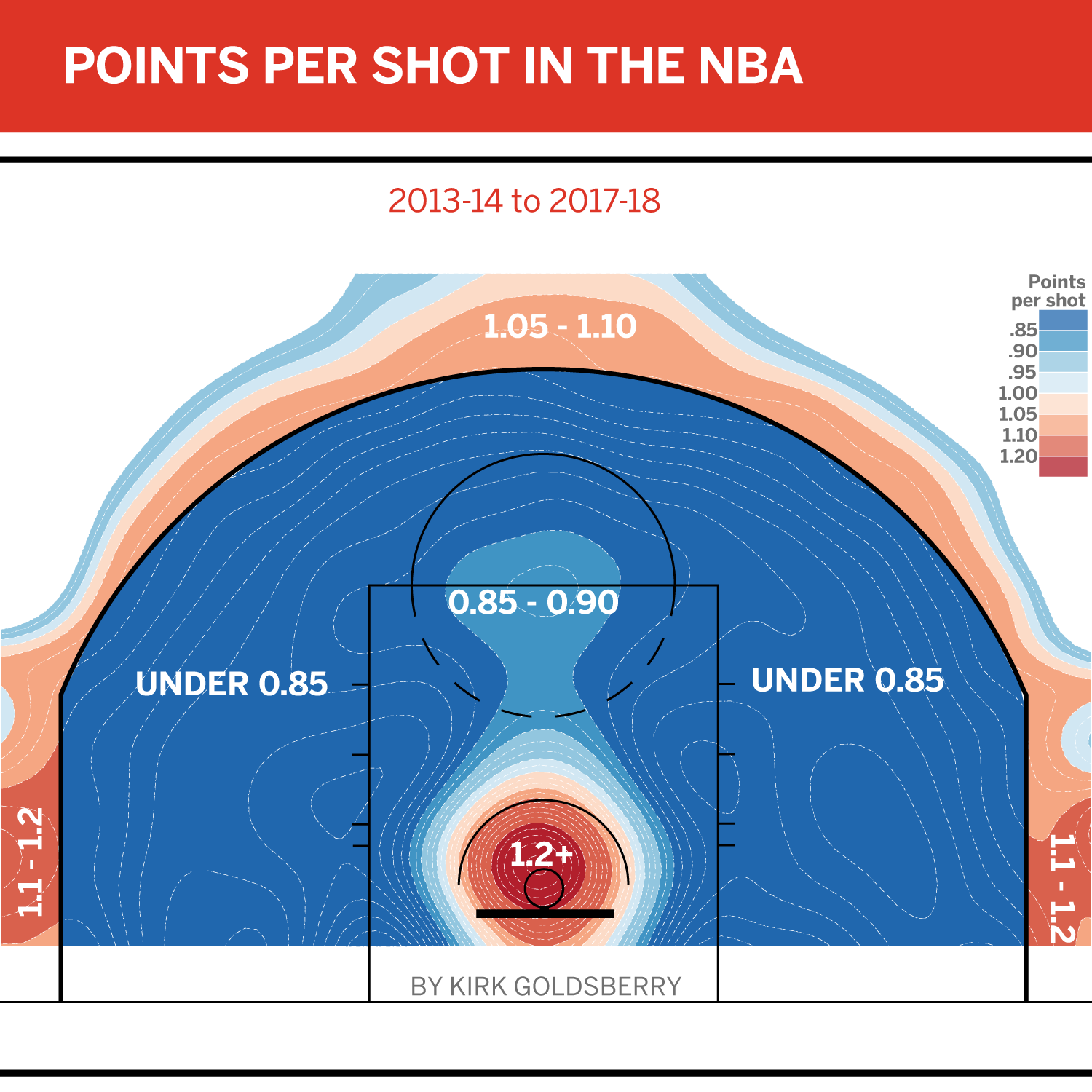

Anthony was never able to combine volume and efficiency as well as the other top scorers of his era. But a closer look here reveals that the league’s best young scorers are putting up much higher TS% than the older guys ever did. The MVPs of this decade are all more efficient, thanks in large part to adopting analytically correct shot diets that emphasize 3-point shooting while limiting the midrange.

Here’s the thing about the best shooting-efficiency metrics in a sport that awards 50 percent more points for 24-footers than 21-footers: They are just as much a reflection of where a player shoots as they are how good a shooter he is.

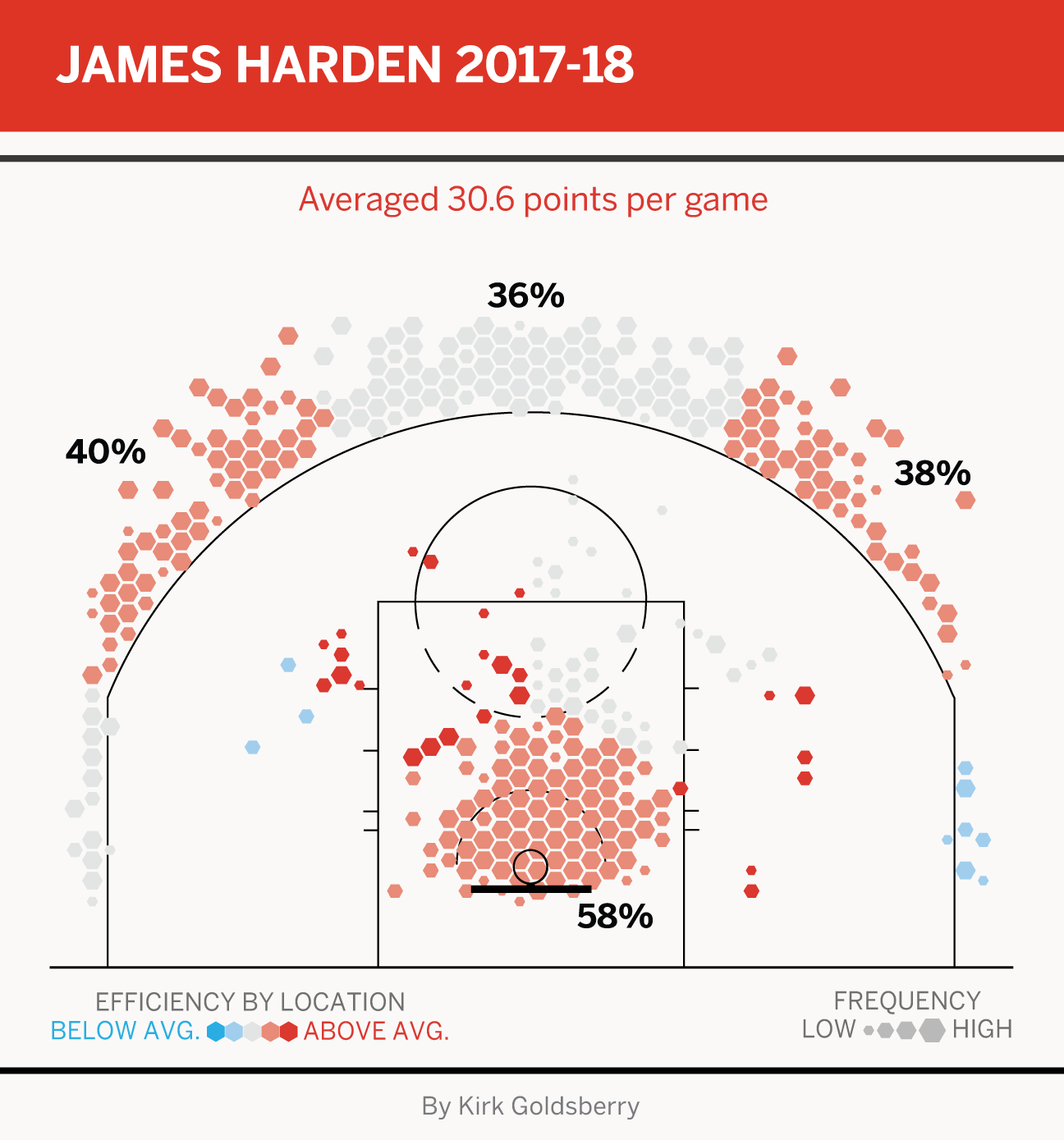

It wouldn’t matter if Carmelo Anthony and Kobe Bryant were more gifted shooters than James Harden. Harden’s stats look better because he avoids the midrange as much he as avoids shaving cream.

Harden’s analytically correct shot diet is the key to his game. Anthony made 44.9 percent of his shots in 2012-13. Harden made the exact same amount in 2017-18, but his TS% dwarfs Melo’s because Harden took more 3s and free throws than any other player in the league.

Zero-sum superstardom

Three-point shooting is just a symptom, and analytics are agnostic. The style of play we’re watching right now — and the style that is incompatible with Carmelo — can also be attributed to a handful of legislative decisions that intentionally reformed the game. If Melo is a dinosaur, then the rule changes of 2004 just might be the meteor.

The champion 2003-04 Detroit Pistons blended hand-checking on the perimeter and clogging up the paint as key means to stifle Kobe Bryant’s offense in the NBA Finals. They muddied up the game and held the vaunted Lakers to fewer than 90 points in each of their four victories. For some, it was a brilliant defensive triumph, but for others it was ugly. And ugly wasn’t good for a league desperate to pull itself out of its post-Jordan malaise.

Following the 2004 Finals, the NBA decided to change some things, as recapped here: “New rules were introduced to curtail hand-checking, clarify blocking fouls and call defensive three seconds to open up the game.”

Those changes jolted the entire value system of the NBA at the beginning of Melo’s career, elevating guards and wings while demoting big men. Suddenly there were new kinds of superstars. Steve Nash, a brilliant yet relatively slight playmaker, emerged to win the league’s next two MVP awards as he ran the league’s fastest and most open offense.

But superstardom is a zero-sum game. As guards ran wild, lateral quickness and switchability started to become more important for larger defenders. It didn’t happen overnight, but size and strength gradually became less important for bigs as speed, spacing and versatility became paramount.

Consider this: In the 10 years before the 2004 rule changes, the NBA handed out its MVP trophy to bigs seven times. In the 14 years since, it has happened only once. Bigs are more replaceable than ever, and so is interior play.

“The inside game is kaputski.” Popovich said last week. “You’ve got to have downhill players. You’ve got to have people that can penetrate and kick. You’ve got to have people who can switch. You’ve got to have big guys who can play little guys.”

As an analyst, I’ve been among the foot soldiers in the Moneyball brigade. But as a fan watching while the league chases the efficiency dragon further down the trail, it’s worth asking: What are we sacrificing in the process?

If present trends continue, we will never see gorgeous midrange monsters like Kobe, Melo, Dirk or Jordan again. That’s some of the beauty we will lose, but we will see a lot more Hardens in part because the league is well aware of the stats encoded here:

Like MJ and Kobe, Carmelo Anthony loves to shoot from those blue areas. Unfortunately for him, in a league obsessed with analytical correctness, nobody finds that valuable anymore. That beauty is old-school now.