Steve Spurrier loves to tell the story about playing golf years ago with then-North Carolina basketball coach Dean Smith and then-Kansas basketball coach Roy Williams.

It was sometime in the early 1990s, and the three coaches were at a charity event in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

“Are you guys going to get a playoff in football?” Smith asked Spurrier, who was only a couple of years into his tenure as Florida’s football coach.

Spurrier shrugged and said, “Aaah, I don’t know. Everybody just sort of plays their season, then the bowls come in and pick the teams they want, and then after they play, they get a bunch of sportswriters together and they decide who the national champion is going to be.”

The Head Ball Coach then looked at his two Hall of Fame hoops counterparts and asked his own question: “How would you boys in basketball like it if you did it like that?”

Smith looked at Spurrier and quipped, “We wouldn’t, because that’s stupid.”

So, 25 years ago, the Bowl Championship Series was created in an attempt to move beyond the polls and determine a clear national champion on the field. The BCS gave way to the College Football Playoff in 2014, but it was a major step in helping shape the postseason. That evolution takes another significant turn in 2024, when the playoff field expands from four teams to 12.

As he looks back today, Spurrier, who won a national championship at Florida in 1996, wonders what fans would do if media members and active coaches still made the call on who walked away with the trophy.

“Coach Smith was right,” Spurrier said, “it was stupid.

“It took a while — too long, really. But playoff sports is what America is about.”

THE BCS WAS created in 1998 by then-SEC commissioner Roy Kramer as a way to pair the two highest-ranked teams in a national championship game at a traditional bowl site. The BCS and its precursors, the Bowl Coalition (1992-94) and Bowl Alliance (1995-97), were designed to create a No. 1 vs. No. 2 bowl matchup every year. That previously had happened only eight times.

Prior to the Coalition and Alliance, the postseason was rather chaotic with bowls scrambling to line up teams before the regular season ended. Many of the bowls had tie-ins, such as the SEC champion playing in the Sugar Bowl and the Big Ten and Pac-10 tied to the Rose Bowl, but there were also at-large slots. For the bowls, that meant the business side of locking in attractive teams with hungry fan bases flocking to their cities was the priority, not setting up matchups to determine the national champion.

“We knew we had to do something differently, especially when you had bowls cutting deals well before the end of the regular season and split national championships in three of the previous eight seasons,” said Mark Womack, who was Kramer’s right-hand man and remains the SEC’s executive associate commissioner. “Roy had the vision of putting together a game and twisting as many arms as he had to.”

New Big Ten commissioner Tony Petitti, then ABC Sports’ vice president for programming, was part of a meeting nearly 30 years ago that set the wheels in motion to get the Big Ten and Pac-10 to buy into the BCS concept, which was a critical piece. Those talks in 1995 were supposed to be about an extension of the Rose Bowl television deal.

“We started talking about how things were shifting in college and how 1 vs. 2 was becoming more important,” Petitti recalled.

After the Big Ten, Pac-10 and Rose Bowl officials huddled to talk among themselves, it was obvious they were none too pleased.

“We were basically booted out of the meeting,” Petitti said with a laugh. “They told us we should go home. I remember my boss [Dennis Swanson] saying when we got back in the car, ‘That was a good first step,’ when I was thinking it was the worst meeting I’d ever been in.”

The seed was planted, though, and Kramer traveled all over the country meeting with different parties to make the BCS a reality.

“Basically, from that first meeting, it took 12 to 15 months to really get everybody in line,” Petitti said. “Give Roy, [Big Ten commissioner] Jim Delany, [Pac-10 commissioner] Tom Hansen and all the Rose Bowl folks credit for thinking differently. But that’s how it started.”

So starting from scratch, Kramer and his trusted colleagues, Womack and Charles Bloom, went to work on their whiteboard in the SEC offices after getting the go-ahead from commissioners from the other conferences. Bloom, then director of SEC media relations, still has some of the notebooks from those early meetings and remembers getting emails from Kramer at 3 o’clock in morning on Sundays.

Bloom said they did 10 years of research prior to finalizing the formula. They worked in a small library on the first floor of the SEC offices.

“This was when everything wasn’t on the internet and we were using record books we had on file that had all the scores from games and doing all the research by hand,” Bloom said.

The plan was to utilize the AP poll, which was voted on by media members, and the coaches poll, but because the polls themselves were part of the problem and susceptible to voters’ biases, Bloom suggested they add computer rankings as part of the formula. Kramer also asked statistics guru Jeff Sagarin to come up with a strength-of-schedule rating.

The original formula included the two polls (AP and coaches), a composite of three computer rankings, a strength-of-schedule element and a point added to a team’s final ranking for every loss — all coming together to produce a score where lower was better.

Even with the BCS in place, Kramer, now 94, knew there would be detractors and that there would need to be tweaks to the system along the way.

“I don’t think anybody ever believed it was a final solution to anything, and nobody thought it was perfect,” said Kramer, who retired as SEC commissioner in 2002. “But whether you liked it or cursed it, it was a better solution to anything that we’d had in the past. So at the moment, I still think it accomplished what we wanted it to.”

And, yes, there was plenty of controversy and angry coaches and fan bases on a regular basis.

“You should have read some of my mail. I kept a lot of it,” Kramer said with a hearty laugh.

Over the years, the BCS formula was tinkered with several times. In 1999, five more computer rankings were added to the mix. In 2001, a “quality wins” component was added to emphasize strength of schedule, and margin of victory was eliminated in 2002. All the while, fans and media alike screamed that the whole thing was rigged or bordered on being a cartel for the blue bloods of the sport.

In 2010, Dan Wetzel, Josh Peter and Jeff Passan of Yahoo! Sports co-authored a book titled “Death to the BCS,” which was so popular it was later updated and revised.

“I don’t think it was so much that people hated the BCS. They just wanted a playoff, and I knew it was inevitable that we were going to get one,” Kramer said. “I also knew that as soon as we arrived at a number of teams in the playoff that everybody would want that number to increase. There’s always going to be scrutiny, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. People were leery of the BCS computers. Now they’re leery of who’s on the selection committee and what perceived biases they may have.

“I sort of sit back and grin. It looks like they’re still having a little controversy and probably always will.”

IN ITS VERY first year, the BCS flirted with disaster. Eventual national champion Tennessee, Kansas State and UCLA all went into the final week unbeaten. During that week, Sagarin said he had run the numbers and that if all three teams won, he projected Tennessee would drop to third in the rankings and be on the outside looking in even though the Vols were No. 1 in the BCS standings that week.

Kramer called Sagarin and told him to keep his “damn mouth shut.” In the end, it worked itself out because double-digit underdog Texas A&M stunned No. 3 Kansas State in double overtime, and Miami rallied to upset No. 2 UCLA.

But that was just the start of the growing pains.

The 2000 season brought some serious drama as Florida State and Miami both finished the season 11-1, but the Hurricanes had beaten the Seminoles 27-24 the first week of October. Miami was ranked No. 2 and Florida State No. 3 in both polls to end the regular season, but the Seminoles leapfrogged the Hurricanes in the final BCS standings thanks to superior computer rankings.

Naturally, then-Miami coach Butch Davis and the Miami fans were furious, with Davis calling the BCS formula “convoluted.”

Then-FSU coach Bobby Bowden didn’t really disagree. “I feel lucky, but the thing is the formula was made before the season ever started,” he said at the time. “The formula spit this thing out that it was us. Therefore, I feel good about it.”

Florida State went on to lose an ugly 13-2 decision to Oklahoma in the title game.

Then there was 2003, which ended with a split national championship, exactly what the BCS was supposed to prevent.

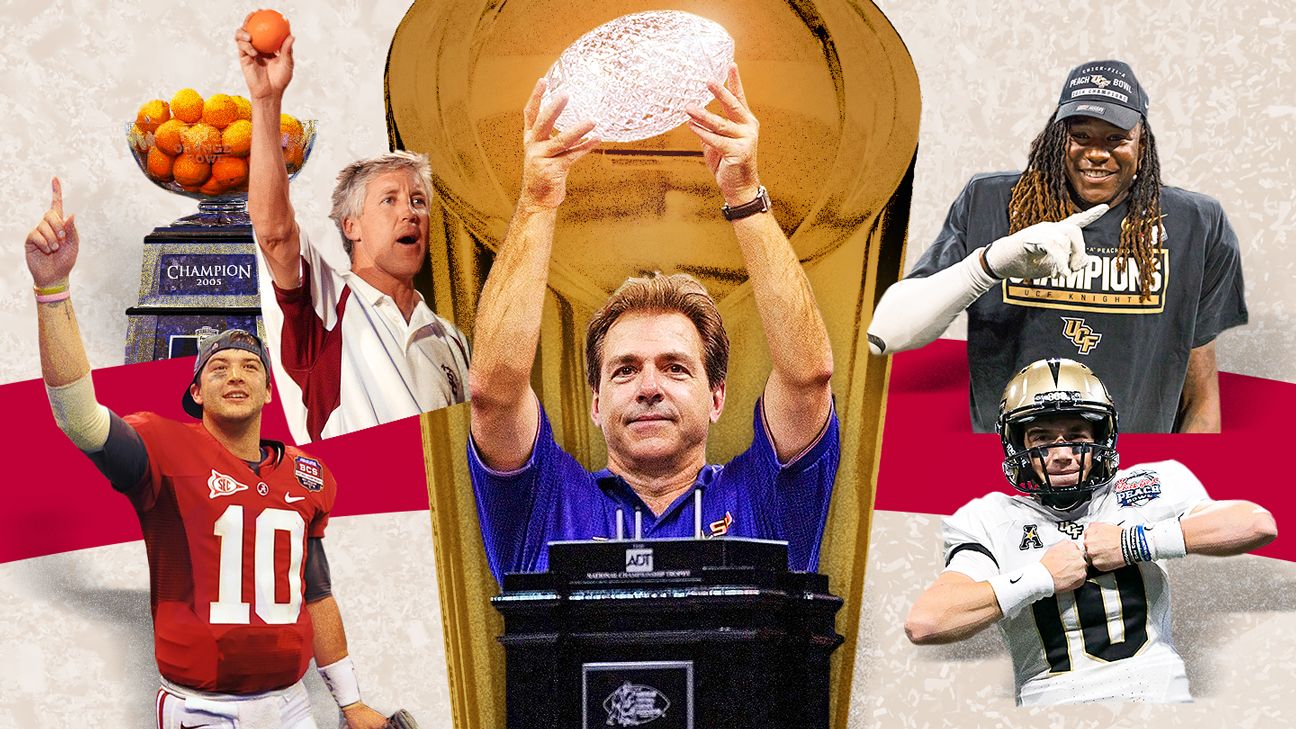

LSU, under Nick Saban, beat Oklahoma in the Sugar Bowl to win the BCS national title. The Sooners had been blown out by Kansas State 35-7 in the Big 12 championship game and fell to No. 3 in both polls, but they still got a spot in the BCS title game. USC finished the regular season No. 1 in both polls but was hurt in the final computer rankings when two teams it beat, Notre Dame and Hawaii, lost to Syracuse and Boise State, respectively, in their final games.

The Trojans were further hurt by margin of victory being taken out of the computer rankings that year as BCS brass feared teams would run up scores to boost their numbers.

LSU squeezed past USC by 0.16 of a point in the final BCS standings to grab the No. 2 spot behind Oklahoma. USC was left to face Michigan in the Rose Bowl and won 28-14. The Trojans held on to the No. 1 spot in the AP poll and a share of the national title.

The coaches who voted in their poll had agreed to select the winner of the BCS National Championship game No. 1 on their ballots. But South Carolina’s Lou Holtz, Oregon’s Mike Bellotti and Illinois’ Ron Turner went against that agreement and voted USC No. 1.

“We knew there was a chance we might run into that, the AP poll voting in a different champion,” Kramer said. “Our goal never changed, though, and that was to create better matchups in bowl games, and hopefully in most years, create a consensus No. 1 vs. No. 2 matchup for the national championship. It didn’t happen that year. The computers liked Oklahoma. I would agree that we probably did change the formula too much trying to adjust to all the observations from previous years.”

In the aftermath, the BCS formula was simplified in 2004 with strength of schedule and the “quality win” component eliminated.

USC was dominant that season and won the national title, but there were five unbeaten teams entering the bowl selections, including SEC champion Auburn. Tommy Tuberville’s Tigers finished third in the final BCS standings and played in the Sugar Bowl, finishing the year 13-0.

Auburn being left out of the national championship game intensified then-SEC commissioner Mike Slive’s desire to see college football adopt a four-team playoff.

“I never wanted to see a season again where an unbeaten SEC champion didn’t even get a chance to play for a national title,” Slive told ESPN years later. “I already believed we needed a playoff in college football. I knew after 2004 that we absolutely were going to get there.”

THE BCS ERA left virtually no hope for a Group of 5 team to get into the championship game. Boise State had three unbeaten regular seasons in 2006, 2008 and 2009 and never finished higher than sixth in the final BCS standings. The Broncos won the Fiesta Bowl to cap both the 2006 and 2008 seasons, and their 43-42 win in overtime against Oklahoma in the 2007 game remains one of the more thrilling bowl finishes in history.

Chris Petersen, who went on to coach Washington, led those powerhouse Boise State teams. In 2010, the Broncos had vaulted to No. 4 in the BCS standings and were riding a 24-game winning streak, but lost a heartbreaking 34-31 road game to Nevada in overtime on the final weekend of the regular season after missing a 26-yard field goal that would have won it in regulation.

“I think that’s the best team we ever had, when we lost that last game to Nevada and Colin Kaepernick and missed the field goal there at the end,” Petersen said. “We were winning 24-7 and played one bad half of football, and it cost us.”

The Broncos won two games over nationally ranked Power 5 foes that season (Virginia Tech and Oregon State).

“I never got hung up on ‘We had to win a national championship or had to get to the BCS National Championship game,’ because I knew getting one of those top two spots was going to be hard no matter how many games we won,” Petersen said. “I just felt like if we could run the table, there was no way they could leave us out of the BCS bowl games.

“I guess it might have been interesting had we not lost that Nevada game in 2010, but there was nothing to talk about after, not with a loss.”

In 2008, Utah of the Mountain West Conference was the only unbeaten team in the FBS but didn’t get a chance to play for the title. The Utes beat four nationally ranked teams, including Michigan on the road to open the season, but finished sixth in the final BCS standings. They beat Alabama in the Sugar Bowl to close out a 13-0 campaign.

After the season, the Mountain West proposed an eight-team playoff that would have eliminated the BCS formula and created a 12-member committee to choose the at-large teams, but it was rejected by the BCS committee.

That May, Slive presented a plus-one model, which was a version of a four-team playoff, but that also was shot down.

Even President-elect Barack Obama was calling for a playoff. In a “60 Minutes” interview that November, he suggested having an eight-team playoff and added, “I don’t know any serious fan of college football who has disagreed with me on this. So I’m going to throw my weight around on this a little bit. I think it’s the right thing to do.”

NEARLY EVERYBODY ASSOCIATED with college football agrees the 2011 season sealed the fate of the BCS. If it wasn’t already inevitable, there seemed to be no doubt a playoff was coming after Alabama and LSU met in the BCS title game, a rematch of their regular-season affair that LSU won 9-6 in overtime.

Oklahoma State was the most explosive team in the country that season, averaging 51.7 points per game, and the Cowboys were No. 2 in the BCS standings when they were upset 37-31 in two overtimes by Iowa State on Nov. 18. Kramer contends that game had more to do with reshaping college football’s system for determining the national champion than any other game during his tenure. “That’s the game that put Alabama back in the mix,” Kramer said.

But OSU coach Mike Gundy and other critics of the BCS said the Crimson Tide should have never been back in the mix, especially after Oklahoma State routed Oklahoma 44-10 two weeks later to win the Big 12 championship — on a weekend when Alabama sat at home because it hadn’t won its division in the SEC. Oklahoma State finished behind LSU and Alabama in both of the polls, and although the Cowboys were No. 2 in the computer rankings, they finished No. 3 in the final BCS standings.

“We should have been in the championship game that year, and if we had gotten that chance, we would have played LSU and won,” Gundy told ESPN. “They were an overload-the-box, man-to-man team on defense, and you could not play our team in man that year. We were too good. That still bothers me, that we didn’t get a shot.”

Womack knew an all-SEC title game wouldn’t bode well for the future of the BCS.

“I agree with Roy. That was the year that ended any debate,” Womack said. “Having two teams from the same conference playing in a rematch solidified that we were going to a playoff. But once you watch those two teams and look at the talent on those teams [Alabama and LSU], it’s hard to argue those weren’t the two best teams around.”

Just as Kramer predicted, the College Football Playoff became a reality a few months later, in June 2012, beginning with the 2014 season.

THE HOOPLA SURROUNDING the first year of the playoff was immense. The goal, according to CFP executive director Bill Hancock, was to pick the “four best teams,” with the committee instructed to consider strength of schedule, head-to-head matchups, conference championships, common opponents and injuries, among other factors.

Ohio State went on to win the national title despite losing to unranked Virginia Tech the second week of the season, but expanding the field to four teams didn’t mean an end to controversy.

Entering the final weekend of the regular season, TCU was third in the CFP rankings, Ohio State was fifth and Baylor sixth, with all three teams having one loss. The Big 12 at that time had no conference championship game, and in their last games, TCU hammered unranked Iowa State 55-3, and Baylor beat No. 9 Kansas State 38-27. The Horned Frogs and Bears finished as co-Big 12 champs, although Baylor won the regular-season matchup in a wild 61-58 affair. Meanwhile, Ohio State delivered a 59-0 pasting of No. 13 Wisconsin in the Big Ten championship game.

Committee member Steve Wieberg told ESPN in 2018 that he had a “knot in his stomach” as the games played out and realized that “two somebodies are going to be left out.”

Gary Patterson, then TCU’s coach, also had a knot in his stomach. He knew what was coming despite the Frogs’ dominant showing in their last chance to impress the committee. As he and then-Iowa State coach Paul Rhoads met at midfield for their postgame handshake, Rhoads said, “Good luck in the playoff, Gary.”

Patterson grimaced and said, “No way they’re going to let us in, Paul, in the first year.”

When the final playoff rankings came out, TCU fell from No. 3 to No. 6. Ohio State moved up to fourth — and into the playoff. Baylor was fifth.

Even now, Patterson is befuddled at how TCU could fall three spots after winning by 52 points.

“I mean, we were already No. 3 and didn’t do anything to make ourselves look bad,” Patterson said. “We had a share of our conference championship, which was supposed to matter. It doesn’t do any good to bitch about it now and say we were better than those four teams that went ahead of us.

“There are good people on that committee. It’s a hard job. I wouldn’t want their job. That’s why I’ve always been an eight-to-12-team playoff guy and glad to see we’re finally getting there.

“It’s just too late for that team, and I hate it for those players.”

Hancock explained to ESPN at the time that the committee wanted to get away from the “old poll mentality” and look at the season in its entirety in picking the final four teams.

“The committee has a different mentality about it,” Hancock said. “Ohio State’s résumé improved. Baylor’s résumé improved with a victory over a good K-State team, and TCU had the misfortune of playing a team that would finish 2-10 on the last weekend. It helped people understand it’s a new day.”

By 2017, there was already some momentum for the playoff to be expanded, but it went into overdrive when two teams from the same conference made the four-team playoff for the first time. Those two teams, Alabama and Georgia of the SEC, won their semifinals and played for the national championship, with the Crimson Tide winning 26-23 in overtime.

Part of the rub was that Alabama didn’t win its division (similar to 2011 in the BCS days) but still got into the playoff as the No. 4 seed. Wisconsin was No. 4 in the next-to-last rankings but lost to Ohio State in the Big Ten championship game. The Buckeyes’ undoing was a 31-point loss in November to an Iowa team that finished 7-5.

But nobody was more upset about the way things played out that season than UCF, which won 25 straight games during the 2017 and 2018 seasons but never got higher than No. 8 in the final CFP rankings. The Knights, of the American Athletic Conference, were 13-0 in 2017 and beat Auburn in the Peach Bowl. But they were an afterthought when the committee sent in its final rankings, sitting at No. 12.

Tennessee athletic director Danny White, who was UCF’s AD at the time, still bristles at it all.

“I said it then and will say it now. It was ridiculous … to finish 12th?” White said. “I knew we weren’t getting in, but I wasn’t going to be quiet about it. Then we go undefeated again in 2018 in the regular season, and after we made all that ruckus in 2017, so many people went on record and said, ‘If they go undefeated again, then it will be another story.’ But the rhetoric quickly changed. We had ranked wins in the American, but it never really seemed like that had the same weight as even an unranked win against a Power 5 brand.

“It wasn’t a real postseason, not if we were all supposed to be part of the same subdivision in football.”

White immediately proclaimed the Knights national champions after their Peach Bowl win following the 2017 season, and quarterback McKenzie Milton said the playoff should be canceled. UCF had T-shirts and a parade to celebrate its national title, and the Colley Matrix system, a mathematical ranking that had been part of the BCS formula, designated UCF as its national champion that season, as noted in the official NCAA record book.

“It was a real-life example of why we needed to expand the playoff,” White said. “It’s really hard to go through a whole season and win every single game. Those kids and those coaches put pressure on the system, that it was time to change. It was a pretty bold statement, and that group of student-athletes from the 2017 season should feel very much responsible for a big part of playoff expansion.”

A Group of 5 team, Cincinnati, finally made the playoff in 2021, as the Bearcats went 13-0 in the regular season but lost to Alabama in the semifinal at the Cotton Bowl. Then, at the start of the 2022 season, a 12-team playoff was approved.

NOW THAT THE college football playoff is expanding to 12 teams starting in 2024, the question is: How much longer before it expands even further?

And even more pressing: How will the format change in 2024 and beyond in the wake of conference realignment? Most in the sport agree it’s going to change, but to what degree?

The late Mike Leach used to opine that college football needed to go to 64 teams, similar to college basketball. His president at Mississippi State, Mark Keenum, was not a fan of the idea. Keenum is now the chair of the College Football Playoff board of managers. He proposed a 12-team format with no automatic qualifiers last summer, but that idea did not receive enough votes to pass.

“What we’ve learned over the years, going back to the BCS, is that there’s a real desire to get it right when determining the national champion, and that desire has not changed no matter how much things have changed around us,” Keenum said. “I understand there’s great prestige in being a major conference champion. But at the end of the day, we want the best teams, period, competing in our nation’s playoff to determine the champion.”

The 12-team model that was approved last year would include the six highest-ranked conference champions and six at-large teams, with the four highest-ranked conference champions seeded 1 through 4 and receiving first-round byes. The first-round games would be played on campus sites.

But with the Pac-12 whittled to two teams, Keenum said there will be very “earnest discussions” about what the right format is going forward, not to mention what distribution of the revenue generated from the CFP will look like.

“I’m looking forward to 2024, but clearly we’ve got a good bit of work to do,” he said.

Petersen, whose 2017 Washington team was the last Pac-12 team to make the playoff, hopes that whatever tweaks are made aren’t locked in for too long.

“Let’s be sure that we’re not so far out there in a contract that we can’t assess how something is working,” said Petersen, now a Fox studio analyst. “We want to be able to look at this and say, ‘This was really good or not so good,’ whether it’s the way teams are seeded, home-field advantage or whatever it is.”

Petitti, the Big Ten commissioner, agrees that flexibility is key, as is protecting the importance of the regular season.

“Meaningful games in the regular season can never go away,” he said. “I think the 12-team format that’s been talked about does that. It doesn’t mean that it won’t evolve down the road. Postseason formats always seem to change in pretty much every sport, right? Now, how fast does that happen in college football? That’s hard to predict, but if you look at the history of postseason formats, they change.”

Kyle Whittingham, in his 19th season at Utah, isn’t sure any of this playoff debate is going to matter down the road. He’s convinced there’s more upheaval coming.

“Everything is going to be predicated and set up on where’s the most money, and that’s why you’re going to see another round, at least, of change, and it’s ultimately going to streamline into one or two superconferences,” Whittingham, whose school is jumping from the Pac-12 to the Big 12 next year, said in August. “They’ll govern themselves. They’ll break off from the NCAA. They’ll have their own playoff, and that’s just where it’s heading. I don’t think there’s any way around that.”

SEC commissioner Greg Sankey, one of 10 FBS commissioners on the playoff committee along with Notre Dame athletic director Jack Swarbrick, has run 41 marathons in his life, and he has taken on a marathon mentality in navigating the changes in college sports, including the playoff.

“It’s going to be a long run, not a sprint,” he said.

Sankey said patience will be needed as college football tries to figure out its future. He doesn’t see a drastic near-term move, such as 40 or so of the top football programs breaking away from the NCAA and having their own governance, commissioner and playoff.

“I think those have been, in my view, really unsophisticated observations,” Sankey said. “That doesn’t mean the individuals making the observations are not thoughtful. But I think it doesn’t represent a full consideration of college sports, and we still are in these positions charged with administering college sports, not just college football.”

The current CFP contract goes through the 2025 season. Negotiations for a new media rights deal, which would start with the 2026 season, will begin sometime during the first part of next year.

“I don’t think there’s any system or format that’s going to please everyone,” said Alabama coach Nick Saban, who won four national titles in the BCS era and three more in the playoff era. “We don’t all play the same schedules. We don’t play in the same conferences. It’s not the NFL.

“But once we went down the playoff road, we all had to be willing to accept the consequences. Everything now is geared toward the playoff. I’m not saying that’s necessarily a bad thing. I’m just saying that’s the way it is. I’ve always said that if we’re going to do this, let’s do it in such a way that the best teams are in the playoff regardless of conference affiliation.

“In a lot of ways, we’re still trying to figure out how to do that.”