Jarrod Bullard had just been asked by a reporter what his fiancée, Patrice, thinks of this obscure hobby of his, this video game that takes up all of his free time. In a moment of serendipity, she beeped in on the other line.

“Hold on,” he said in a moment he would quickly regret, “I’ll let you get her opinion on it.”

“It’s a labor of love. I love the game. I love college football.”

NCAA Football fan Jarrod Bullard

Just like that, Patrice was off and running, noting how Bullard’s level of dedication is akin to an actual relationship. All that time he spends deciphering clips on YouTube and poring over preseason college football magazines? All those numbers he inputs? It takes months — “Months!” she reiterated — for him to finish.

And for what?

“After all of this and putting in all the information, did you know he doesn’t even play the game?” she said.

She can’t wrap her head around why a video game — let alone one that’s no longer in production — demands so much of his attention. She calls him “crazy and obsessed” with EA Sports NCAA Football.

He just can’t (or won’t) let it go.

A 17-year veteran of law enforcement who once walked onto the football team at USF, Bullard works with a group of nine gamers to keep the defunct franchise alive. Each offseason, they go through a painstaking process to input data to build out the updated rosters of all the FBS programs.

Every player is created from scratch, down to his name, likeness and hometown. Then there’s the empirical method they’ve devised for assigning player attributes like speed, agility and strength — those “little stupid numbers,” as Bullard’s fiancée put it.

“She’ll get up at 3-4 in the morning and go, ‘Ah! You’re still up working on this game? You’re not even playing!'” Bullard said. “But I’m editing. Let. Me. Live. I’m living my best life right now.

“She thinks all of us are psycho. She calls us nerds.”

“She’ll get up at 3-4 in the morning and go, ‘Ah! You’re still up working on this game? You’re not even playing!’ But I’m editing. Let. Me. Live. I’m living my best life right now.”

Jarrod Bullard

She’s not necessarily wrong, if you take the endearing version of the word. They’re impassioned. They’re dedicated. And, yeah, they’ve been known to nerd out from time to time.

But because of their attachment, they’ve kept a game millions of people have spent countless hours playing from going extinct.

“It’s a labor of love,” Bullard explained. “I love the game. I love college football.”

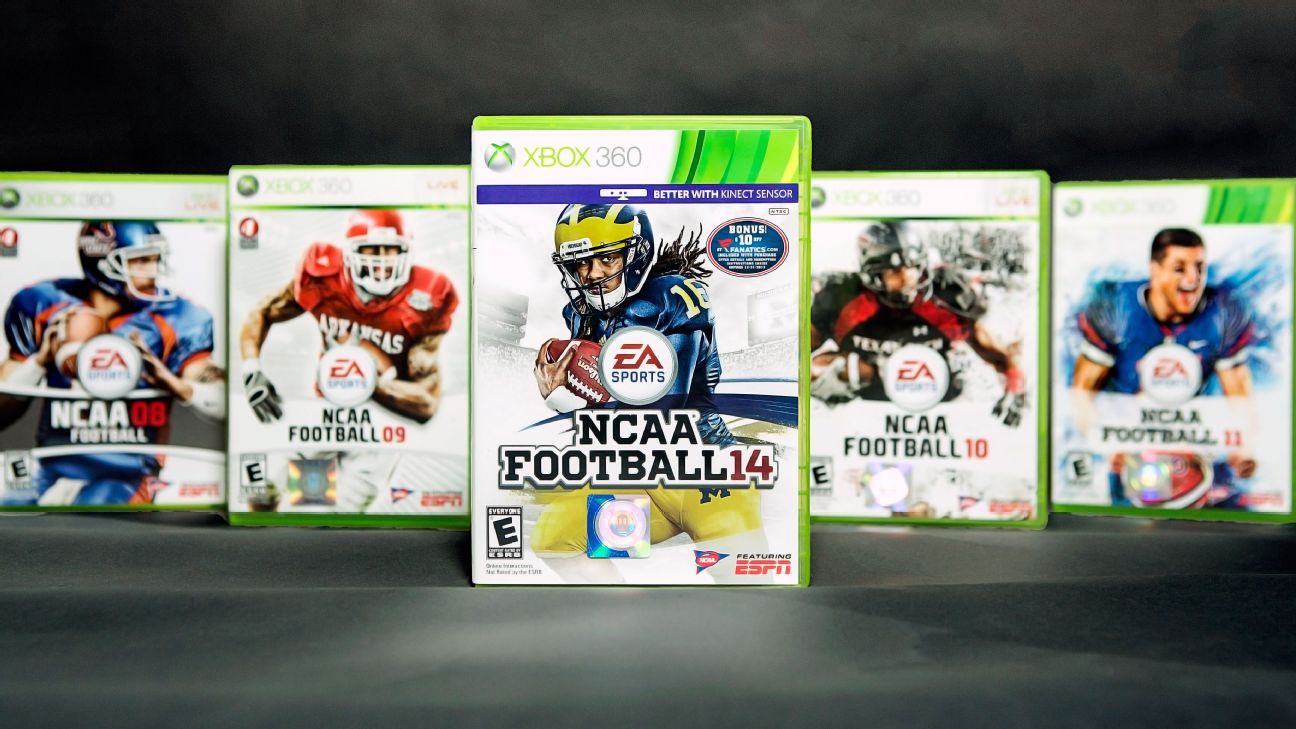

Five years ago this week, NCAA Football hit the shelves for the final time. Michigan quarterback Denard Robinson graced the cover of the game, which sold roughly 1.5 million copies.

It was the end of an era. No longer would its annual release mark the unofficial start of the college football season. A multimillion-dollar franchise adored by fans was discontinued, done in by a lawsuit brought against the NCAA by former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon against that challenged the use of college athletes’ names and likenesses without compensation.

At least a half-dozen petitions have been created on change.org to resurrect the game. One petitioner wrote that he signed because, “Without NCAA Football life is dull!”

And who could blame him? The “Road to Glory” and “Race for the Heisman” modes were like catnip for college football enthusiasts. The fight songs, the mascots, the screen-shaking crowd noise captured the essence of the sport. It didn’t matter whether you were a fan of Florida or Florida A&M, you had a way of building your own digital dynasty.

For gamers like Austin Pope, seeing the franchise shuttered was an especially difficult pill to swallow. It wasn’t just that he and his brothers had spent countless hours playing the game growing up. It was that the dream of one day being in the game — a dream he had long before he ever received his first scholarship offer — might never come to fruition.

“I always thought growing up, I can’t wait to be on the game, to have my own rating, to have them actually create me,” said Pope, now a veteran tight end at Tennessee. “But then obviously once I got to college they stopped making the game — of course.

“It was just a dream that got crushed.”

“I always thought growing up, I can’t wait to be on the game, to have my own rating, to have them actually create me. But then obviously once I got to college they stopped making the game — of course. It was just a dream that got crushed.”

Tennessee tight end Austin Pope

Pope’s teammate, linebacker Quart’e Sapp, felt the same way. He said he was “disappointed” when he got the news.

Then he paused.

“But,” he said, “to this day some people still have it and update it. I’ve actually played it the last two years a few times.”

He didn’t know who did it or how, but Sapp had seen it with his own eyes: One of his friends had a bootleg version of NCAA Football where he could play as himself.

As it turns out, Pope had seen it, too. Last season’s Volunteers holder, Parker Henry, had downloaded the updated roster to his console.

“It was hilarious,” Pope said.

Hilarious and apparently not all that unusual. Because players at Ole Miss and Florida said they had used the rosters as well.

Florida quarterback Feleipe Franks was amazed when his brother showed him how to download the updated rosters. When he played as himself, however, he had a sinking feeling. His rating was in the low 60s.

“I was garbage,” he said, laughing. “They had me rated so low I didn’t want to play.”

The redshirt sophomore is determined to improve upon that rating in future updates.

“I need to get them numbers up,” he said.

By late August, Franks will know where he stands. Thanks to Bullard and the rest of the editing team, every player and fan of NCAA Football can keep the game alive for another season.

Louis Burhans says it takes him on average 25 hours to finish editing a single team. Multiply that by the 30 teams he’s in charge of and you’re talking about 750 total hours.

Never mind that Burhans has a full-time job and a wife and two children.

“You have to be borderline insane or a superfan — probably both — to do this,” he said. “What rational person would want to sit down and spend 20-plus hours on one team for free? And then do it over and over and over and over?”

He could cut his time in half, but he’s too much of a perfectionist. When he creates a player, the look has to be just right, down to the correct face mask and socks.

When he saw how other gamers were rating players based on feel rather than statistics, he and another member of his team devised a ratings system.

“I call him ‘A Beautiful Mind,’ the way he has the scale set up,” Bullard said of Burhans, referring to the movie about renowned mathematician John Nash.

To get a baseline for each player as a true freshman, they compile a composite rating from several recruiting services. From there, they dig for combine measurements like 40-yard dash times, box jumps and power tosses.

(They don’t trust reported times. “These high school coaches lie so bad,” Burhans said. “They have 270-pound linemen running a 4.3.”)

Each verified combine result then has a corresponding rating. For instance, a receiver with 4.37-second 40-yard dash, a 38-inch vertical and a 40-yard power toss would rate 94 in speed, 88 in jumping and 68 in strength. The scale shifts based on position (i.e., what you think of as strong for a defensive end and a receiver are not the same).

After their freshman season, players then get points based on experience and statistics. A quarterback who completes 70 percent of his passes, for instance, receives a 93 accuracy rating.

There are even corresponding ratings for first-, second- and third-team All-Americans. And even that has checks and balances, with votes tallied from five different sources to avoid a random second-team All-American who appears on one ballot but none of the others.

The system’s not perfect, Burhans said, when it’s pointed out to him that Alabama quarterback Jalen Hurts is going to get only a 70 rating in strength despite his reputation as a weight-room warrior.

“Yeah, I know,” he said. “He’s super strong and I’ve got a dude from Alabama who is always texting me like, ‘Dude, this is bullcrap! He’s squatting 600 pounds!’ But the only reason it’s done like that is I redid the whole entire scale and I made it match the recruits that are created in the game. What I did is I simulated five seasons and the highest any quarterback was in five years was a 70 in strength. So it’s not my personal feelings. If it were up to me it would probably be around 78. But the game doesn’t understand. The game’s physics doesn’t let it understand if you’re a 78 in power and you’re only 220 pounds.”

Yes, physics. Burhans goes that far down the rabbit hole to understand ratings.

Still, he said he hears complaints from fans all the time.

“Alllll the time,” he said. “And it’s crazy because we do it for free.”

There are times he asks himself why he does all this, but then he starts working, gets in a rhythm and “it’s so freaking fun.”

“The game has been gone for a few years now and people are like, ‘I can’t believe people are still playing the game,'” he said.

“But in reality it’s not really the game from 2013. We’re always updating it. It’s different. It’s the same mechanics, same everything else. But it feels like Christmastime when you get that new roster. It makes the game feel alive and new and fresh.”

Ed O’Bannon never thought he’d become a villain in the eyes of video game aficionados.

Granted, he doesn’t blame them for feeling that way. He understands the narrative that’s out there and he doesn’t begrudge anyone their passion. Nevertheless it’s an unfortunate feeling for the 45-year-old who still has fond memories of playing old-school consoles like Atari.

“We used to ride our bikes all over town to the local hamburger joint,” O’Bannon recalled. “They had Ms. Pac-Man, Galaga, Donkey Kong. It wasn’t something I wanted to see go. I didn’t jump into this lawsuit to get video games removed.”

However, O’Bannon was a lead plaintiff in a lawsuit against the NCAA and EA Sports over the use of players’ names and likenesses. EA Sports never used players’ names in its games, but that was about the only thing it didn’t replicate.

When former Alabama wideout Tyrone Prothro testified during the trial, he pointed out how his avatar had exactly the same height and weight he was in college. The game even featured the very same wristbands he was known to wear during games, he said.

O’Bannon said the NCAA cast him as a villain instead of acknowledging that the video game was discontinued because it didn’t want to pay athletes. EA Sports, rather than wait for a verdict, reached a $60 million settlement with the players and never produced another version of its college football or basketball games.

“There is ample opportunity for them to talk about the real reason why the game isn’t being manufactured anymore, but they need a scapegoat,” O’Bannon said. “Coming into this, I knew that I was going to have to fall on the sword.”

The first time O’Bannon meets someone, he said “nine times out of 10” they ask about video games. “I was in the gym the other day and a guy looked at me and said, ‘Hey, I know who you are, you’re the one that got the games taken away,'” he said. “He laughed about it. When I say my name, I expect someone to say that. If that’s what you recognize me for, I refuse to try and change your mind or justify my actions.”

Current players are torn, however. Making money would have been great, but as Tennessee linebacker Sapp pointed out, seeing themselves in the game was worth something, too.

“It wasn’t something I wanted to see go. I didn’t jump into this lawsuit to get video games removed.”

Ed O’Bannon

“It’s a lot of football players, it’s too many to distribute funds,” he said. “And I feel like a lot of the guys would honestly just say, ‘Yeah, I’d like to be in the game.’ That’s like the game.”

In the meantime, hope for its return appears slim. There are those within EA Sports who would love to produce the franchise again, but that would require the NCAA to allow players to be paid and that’s just not a reality at this time.

Ben Haumiller, who worked on the game from 2005 to 2014 and then transferred over to the Madden team, hears from fans constantly about it. At the NFL combine last year, in the middle of doing facial scans for all the rookies, he said former Michigan tight end Jake Butt asked him, “Hey, when is NCAA coming back?” This year, former Louisville quarterback and Heisman Trophy winner Lamar Jackson pulled him aside.

“This is the first class that was high school seniors when ‘NCAA 14’ came out and never had anyone eligible to be [in the game],” Haumiller said. “He’s like, ‘Man, I would have been on the cover.’ He mentioned it was one of his dreams to be on the cover.”

Haumiller, who is a gamer at heart, added: “It’s sweet and painful to talk about.”

Still, he’s buoyed by the game’s enduring popularity and those who update it year after year.

“It’s crazy the detail that they’ve gone into to try to figure out a game that’s five years old and how they can make it still, essentially, as alive as it can be,” he said. “We, on our side of the house, can have nothing to do with that. But I can admire it from afar. That’s the group of people I absolutely love. They put their time and work and investment into it for their own pure joy.”

All it takes is about $20 to buy a copy of the game’s final release online these days. Then, with a little digging, you can download the updated rosters for free and play a version that at least feels like 2018 with familiar stars like Houston defensive lineman Ed Oliver and Stanford running back Bryce Love (both projected 99 ratings) or Penn State quarterback Trace McSorley (projected 93). There’s even a hack that will rig the game to create a four-team playoff.

It might not be the real thing, but it’s awfully close.

ESPN reporter Myron Medcalf contributed to this report.