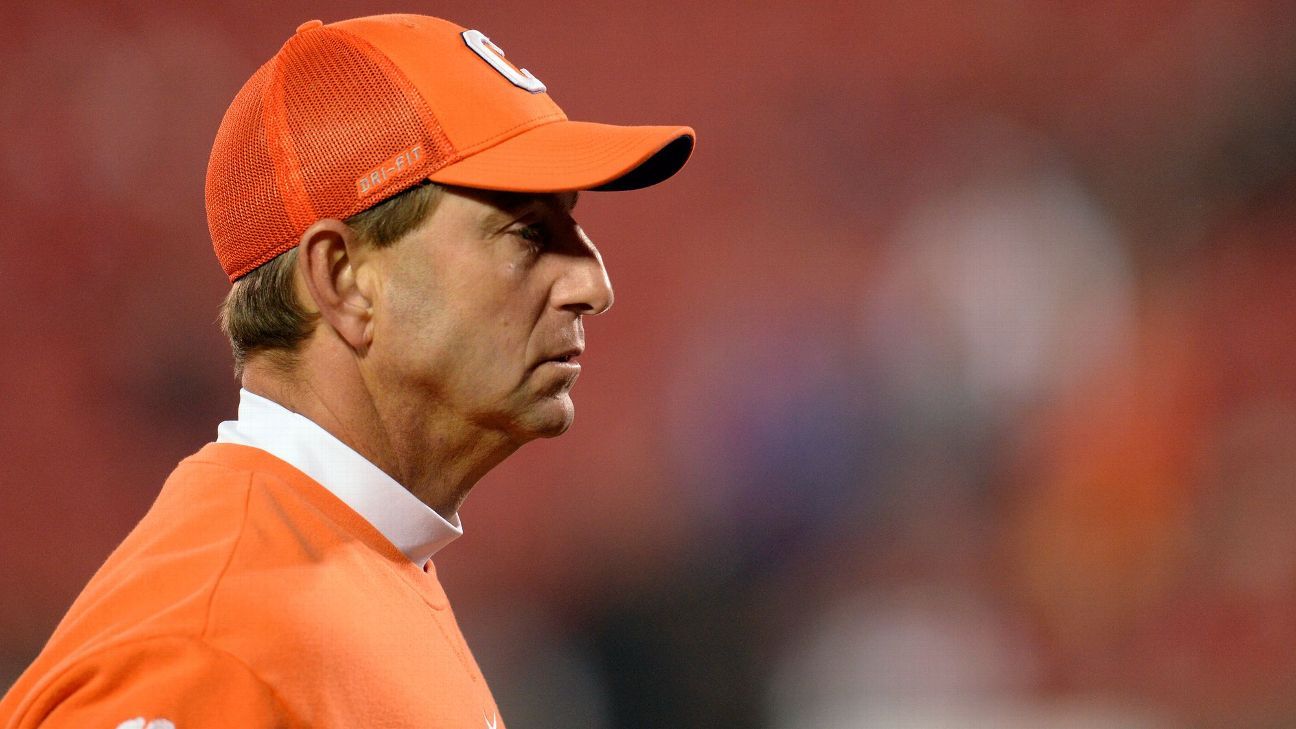

CLEMSON, S.C. — Dabo Swinney insists he doesn’t care about correcting the record, but if he’s being asked, then yes, the narratives he’s heard all offseason are — to use the most colorful phrasing he’s apt to provide — bull crap.

After nearly a decade of unparalleled stability on his coaching staff, Clemson waved goodbye to four assistants this offseason, including both coordinators. There was a time when Swinney was praised as a coach who knew how to surround himself with the best people, but when he replaced Tony Elliott (now head coach at Virginia) and Brent Venables (now head coach at Oklahoma) with two internal candidates, that narrative shifted into something more akin to “Swinney is afraid of outside ideas.”

Bull crap.

There was the time, in 2019, when he offhandedly suggested that, should college football shift toward a professional model, perhaps he’d just quit and head to the NFL. That comment has become shorthand for every out-of-touch coach unwilling to let players profit off their ability, despite Swinney’s repeated insistence he simply didn’t want the college game to lose sight of its educational mission.

In other words, the narrative is bull crap.

Swinney hates the transfer portal.

Swinney cashes $10 million checks while opposing players getting paid.

Swinney would rather lose doing things his way than win by adapting to the modern amenities of the game.

Swinney is selfish, stubborn, hypocritical.

It’s all bull crap, he says, devoid of context and nuance and intent. And yet, travel outside Upstate South Carolina, and the same coach who, just a few years ago, was a fan favorite — the goofy, fun-loving, BYOG-ing alternative to Nick Saban’s joyless process — is far more likely to be cast as the villain.

“People already have their stories written,” Swinney said. “People hear what they want to hear and they can’t wait to get some kind of big click. Nobody cared what I said 13 years ago, but now I guess there’s an opportunity to get some kind of drama. But I’ve never changed.”

Perhaps that’s the problem. Swinney remains rooted in the merits of a system that allowed a poor kid from Pelham, Alabama, to earn a scholarship with the Crimson Tide, to coach for Gene Stallings, to become a head coach without serving as a coordinator, to thumb his nose at every pundit who promised Swinney would fail, only to turn “little old Clemson” into one of the most dominant forces in the sport.

People love an underdog story, and Swinney still wants to cast himself in that role. But he’s not an underdog anymore. He’s at the mountaintop. Or, at least, he was.

Last year, Clemson went 10-3 and missed the College Football Playoff for the first time in six years. After a decade with Venables coaching its vaunted defense, Clemson’s greatest asset is in new hands. Saban has supplemented his championship-caliber roster with some of the best talent to step through the transfer portal, while Swinney insists he can win with his own guys — including maligned QB D.J. Uiagalelei — rather than juice his depth chart with outsiders.

For the first time in a long time, there aren’t simply critics. There are doubters. And for Swinney, that doubt is like gasoline on a fire. Because if there’s one thing that remains steadfastly true about Swinney after all these years, it’s that he loves nothing more than doing something everyone says can’t be done, and doing it his way.

IN THE OLD days — before his $90 million contract and two national championships at Clemson — Swinney was the closest thing big-time college football had to an average Joe. At Christmas, he’d dress up as Santa and invite folks over to his house to see all the lights strung across the lawn, up the walls and around the roof. Before fall camp kicked off each year, he welcomed the team’s beat reporters to his house for dinner, occasionally keeping the party going late into the night so they could all shoot hoops. When Clemson finished the 2015 regular season ranked No. 1, Swinney threw a pizza party for the whole town.

But as his “aw, shucks” approach waded into more fraught topics, a sizable contingent found it less quaint than dismissive.

In 2016, Swinney was asked about then-NFL QB Colin Kaepernick’s decision to kneel during the national anthem. Swinney responded by saying, in part, “I don’t think it’s good to be a distraction to your team.”

“I think a lot of the things in this world, not everything is so bad,” he said. “‘This world is falling apart?’ Some of these people need to move to another country.”

Four years later, amid the outrage following the murder of George Floyd by a police officer, Swinney acknowledged the mistake, calling his Kaepernick comments “a harsh statement.” By then, though, he was embroiled in more controversy.

His response to COVID-19 shutdowns in April 2020 (“We have a saying – T.I.G.E.R.S – this is all gonna end real soon“) seemed tone deaf amid rising mortality rates nationwide. It continued into the fall, when he criticized Florida State for canceling a game because Clemson traveled with a player who tested positive for the virus, saying “COVID was just an excuse to cancel the game.”

While protestors took to the streets in May 2020 under the mantra of “Black Lives Matter,” Swinney showed up in a photo on a fan’s Instagram feed wearing a t-shirt that read “Football Matters.” He was lambasted for insensitivity, though Swinney insisted there was no ill intent. To his mind, the shirt was just a freebie picked up years ago and thrown on before heading to the pool that day. For Swinney, the shirt actually represented an important ethos, that football can save lives, can raise kids out of poverty, as it had done for him, and deliver a better future through competition and education. But at the time, Swinney’s positive vibes were interpreted as the ultimate example of white privilege.

In the aftermath, he acknowledged support for “Black Lives Matter” but also called the criticism “an attack on my character.” Despite that support, he later suggested social justice patches on Clemson’s uniforms were an inappropriate aesthetic.

As Swinney’s longtime coach and adviser Woody McCorvey told The Washington Post in 2020: “Sometimes I think he says some things that, I don’t think I would’ve said that. I’ve tried to educate him, but he has not lived that like I have and other Black kids on this football team have and their parents.”

Away from the cameras, however, Swinney hasn’t shied away from the grim reality of racism. Each year, he invites the team’s seniors to his home for dinner, and in 2020, that meeting morphed into a sort of group therapy session. Swinney listened to stories from his players who’d endured the worst of America, who raged against a system that would never afford them the same opportunities as Swinney had, just because he is white and they are not.

“It was the most powerful moment I had at Clemson,” said Darien Rencher, a former Clemson running back who helped organize social justice protests that year.

Swinney spoke at a rally on campus organized by Rencher and several teammates, including star quarterback Trevor Lawrence. It was a symbolic moment. It was a reminder, Rencher said, that even if Swinney didn’t always have the right words, he would never let his players walk alone.

“We were all aware of the backlash he got,” Rencher said. “In his intent to not be generic, to be authentic, it sometimes backfired because of some words he said that weren’t, at the time, appropriate. But his heart has always been gold. You can’t defend everything but I’ll vouch for his character and who he is as a person. I’d go play for him 10 times over because of who he is.”

WHEN ELLIOTT AND Venables each took head-coaching jobs at the conclusion of the 2021 season, Swinney knew exactly who he wanted to replace them. He made two calls — one to his QB coach Brandon Streeter and another to Clemson defensive analyst Wes Goodwin.

“He called me the day Brent left and said this was what we were doing,” Goodwin said, “and we’ve been rolling ever since.”

No interviews. No calls to outside candidates. Swinney had his guys.

Of Clemson’s 10 assistant coaches, just two had served in an on-field capacity at any other college or NFL job outside of Clemson. It’s a close circle, and after a 10-3 season that stirred worry among Tigers fans for the first time in years, there was a sincere concern that perhaps a few new voices were needed.

“‘Best is the standard, ‘All in’ — it’s those things we hear so many times,” fifth-year senior K.J. Henry said of the Dabo-isms repeated daily around Clemson. “The problem last year is they could be in one ear and out the other.”

But Swinney wasn’t interested in a new message. He wanted people who could sell the old message with a new energy.

Go back to February 2001, and Swinney had been fired at Alabama. He had no paycheck, two kids and a mortgage. He needed a job.

Rich Wingo had one to offer.

Wingo played for Alabama in the 1970s under Bear Bryant and served as a strength coach for Bill Curry when Swinney first walked on for the Crimson Tide in 1989. At the time, Swinney was sharing a bedroom with his mom. It was all they could afford. But Wingo didn’t know all that back then. He just saw a hard-nosed kid who desperately wanted a chance to prove himself.

“I loved his work ethic and how he competed and you’ll never see Dabo on a down day,” Wingo said.

Wingo eventually moved on from football and began a career in commercial real estate sales. He still went to the same church as Swinney, however, and the two kept in touch. When Swinney found himself without a coaching gig, Wingo thought he’d make a perfect salesman.

“I’ll never forget, I told him, ‘Rich, I don’t know anything about commercial real estate,'” Swinney said.

Wingo grinned. He wasn’t hiring Swinney for his experience.

“I can teach you all that,” Wingo said. “I’m hiring you because you’ve got the work ethic, the integrity, the aptitude. You show up and you get the job done.”

Two years later, Tommy Bowden hired Swinney as his receivers coach at Clemson. A few years after that, Bowden resigned, Swinney was named interim coach, then eventually got the job full time. He won, and then he won more and eventually, he won it all. Then he did it again.

None of it makes sense. Swinney never had the right credentials or pedigree, and yet here he is, a resounding success story. How many others can follow that path, too, if someone just gave them a shot?

“Hope is a big part of this program,” Streeter said. “Somebody had to believe in Coach Swinney to get where he is. They saw something in him, and that’s what he’s done with this staff. Give guys opportunities, and you’ll be surprised what they can do with it.”

Swinney rattled off a list of guys he recruited who had no business playing at Clemson: Hunter Renfrow, Grady Jarrett, Deshawn Williams, Adam Humphries, Nolan Turner. They helped build Clemson then found a home in the NFL. That was only possible because Swinney didn’t listen to anyone outside the walls of his program — heck, he probably tuned out a few folks inside it, too — and relied on the same truths that had carried him this far. Read your Bible, Swinney said. Ecclesiastes, chapter four, verse nine: “Two can accomplish more than twice as much as one.” Finding the right people is far more important than finding people with the right résumé.

“It all comes back to chemistry and culture and a group of people working together,” Swinney said. “That’s a very overlooked thing.”

SWINNEY WAS AT ACC Kickoff this summer, happily chatting about one of the construction projects happening around Clemson’s football building. The job will add a few hundred square feet to his office, and he’s already got big plans for it. There are always big plans.

“If you’re not knocking down a wall every year,” he said, “you’re probably falling behind.”

See, Swinney isn’t really averse to change. He’d just prefer to manage it his way.

Another of the big projects at Clemson is a new media facility, a place where recruits can enjoy photo shoots and players can work on name, image and likeness projects. Oh, right — NIL. Swinney’s big on that, despite a persistent perception that he sours the second money reaches the hands of his players.

Clemson hired an NIL coordinator, C.D. Davies, a former CEO at Citi Mortgage and Lending Tree. (“He’s so overqualified for the job, it’s unbelievable,” Swinney said.) Clemson has two NIL collectives that Swinney said are aligned with the program’s values, with a focus on charity and giving back to the community. There’s the new “100 yards of wellness” facility focused on health and nutrition, the program’s applied sciences department and the P.A.W. Journey program that provides life skills and internship opportunities.

“We’ve addressed all these areas,” Swinney said, “but the purpose of the program has never changed.”

And maybe this remains a point of contention with the athlete empowerment crowd. Swinney can roll out all the bells and whistles he likes, but at the end of the day, he remains staunchly against paying athletes directly for their performance. This, too, is where he sees flaws with NIL.

“I’ve always said, NIL, to me, is a part of education,” Swinney said. “It’s enhancing the scholarship opportunities and equipping them even more for real life. The intentions are good and that outweighs the unintended consequences. It’s not intended as a recruiting incentive. Then you throw in the bigger issue of tampering and transfers because there’s no barrier. … There’s not many people going into the portal without a plan. But how did they get a plan?”

Add in all that context, and suddenly Swinney’s avid support for NIL at Clemson can be seen more as a tepid acceptance of the inevitable.

Oh, and then there’s the transfer portal. Swinney’s been among the most conservative coaches in the country when it comes to bringing in transfers. Since 2020, he’s seen 19 scholarship players depart via the portal, while just one has arrived — senior QB Hunter Johnson, who will be third on the team’s depth chart and who, ironically, began his career at Clemson before transferring to Northwestern.

“My transfer portal is right there in that locker room,” Swinney told ESPN this spring, “because if I’m constantly going out every year and adding guys from the transfer portal, I’m telling all those guys in that locker room that I don’t believe in them, that I don’t think they can play.”

Swinney said he did offer two other players in the portal this offseason — offensive linemen with impressive credentials, he said — but both landed elsewhere. Rather than lower his standards, he decided to play with what he has. These are Swinney’s guys, after all. Ride or die.

“We’ve always been inside-out driven, and nothing’s changed,” Swinney said. “I can make whatever decision and people are still going to not like me, they’re still going to criticize me. That comes with winning.”

The sport has changed dramatically over the past few years, and Swinney is willing to adapt. But whether he steps cautiously into the future or marches headlong into a new fight — that part is complicated. NIL, the transfer portal, athlete benefits — it’s good, he said, but it’s not all good. Swinney came up in a time long before NIL, back when, as he joked, “if you gave a guy a candy bar, you went to jail,” and yet college football saved Swinney. He is who he is today because of it. And he’s worried — genuinely — that all this change, all the glitz and the money and the demands, might ultimately overwhelm the things that helped him and his family climb out of poverty and into the penthouse.

“I’m against anything that devalues education,” he said.

Outside Clemson, the conversation is often simpler. Players deserve to be paid. Open and shut. Even Big Ten commissioner Kevin Warren seems to be leaning that way lately. And so all of Swinney’s caveats are met with incredulity.

Inside the walls of Clemson’s football facility, however, his message resonates.

“He has no problem taking the heat,” defensive end K.J. Henry said. “The love he has for his players, the way he just wants everyone to be successful — he talks about it, but to be a part of it is something no one else will ever understand.”

UIAGALELEI WAS SEATED on a stage, just to Swinney’s right, after the 2021 Cheez-It Bowl. Clemson wasn’t supposed to be here but the offense struggled, and Uiagalelei struggled, and so the Tigers missed the College Football Playoff for the first time since 2014. Still, they’d finished on a high note, winners of six straight, and Swinney chalked up a lot of that success to how his QB handled an onslaught of criticism throughout his first year as the starter.

“This guy has the heart of a champion,” Swinney said, sounding as if he was holding back tears. “He’s been in a frying pan all season, and I’ve been right there with him. And he never flinched.”

Ah, that frying pan. Swinney lives in it. Uiagalelei was just trying to survive.

“I’ve said to him,” Uiagalelei said, “‘Man, I just don’t know how you do it. You’ve got people coming at you all the time.'”

There was someone coming for Uiagalelei, too. Clemson welcomed a hot-shot recruit — blue-chipper Cade Klubnik — onto campus this spring, and yet Swinney’s support for the incumbent never wavered. Uiagalelei was his guy, Clemson’s starter. No debate.

Nine months later, Uiagalelei is still replaying that speech in his head because, after a fraught year of on- and off-field turmoil, it was exactly what he needed to hear.

“It means everything,” Uiagalelei said. “He’s been a father figure to me, and for him to go out there and say that publicly, on the record, it’s been amazing.”

It’s the duality of Swinney’s unrelenting optimism — never a down day, as Wingo said — that’s both endearing for his players and coaches and yet, in moments like the Floyd protests or COVID-19 shutdowns, fodder for those who feel he’s dismissive of serious problems. Ultimately, Swinney is probably incapable of approaching the world in any other way.

“I know my purpose in life,” he said. “It’s hard to stay somewhere 20 years if you’re a bad person. I’ve known my wife since first grade. I was in Tuscaloosa for 13 years. I’ve been at Clemson for 20. I know who I am. I’m purpose-driven, so I don’t worry about any of that other stuff. I’ve got thick skin, and I’m focused on what I can control.”

Swinney likes to have his players find a word that defines their season — a mantra of sorts, that provides a through line between the hard times and the end goal. This year, Uiagalelei came up with “Roll the dice.” The idea, Uiagalelei said, is to take a chance on himself, to tune out all the noise telling him something can’t be done and to wager that it can.

It’s an apt metaphor for Swinney’s season, too.

No transfers. No outside hires. No need to reinvent himself. Swinney is betting big on the same blueprint that brought him here.

“Everything we need, we already had here,” Henry said. “Coach Swinney, he sees it before we ever could.”

Swinney’s feet are planted, even as the rest of the world whizzes past in frenetic upheaval. It wouldn’t be fair to suggest Clemson’s 2022 season is about anything more than this particular team’s success or failure, but Swinney’s image has always existed in a space beyond the wins and losses. And so this year, too, carries with it a larger context, one that will either arm Swinney with all the “I told you so” ammunition he needs to fend off his critics or will stoke the embers of a new chorus of Dabo haters.

So, he’ll roll the dice, and he likes his odds.