DAVE WANNSTEDT NEEDED his team to do some studying.

The Pitt football coach was leading the 4-7 Panthers into the 2007 edition of the Backyard Brawl against No. 2 West Virginia in Morgantown as a 28.5-point underdog.

But he wasn’t concerned with showing his players blitzes or screen passes. Instead, he showed them pictures of the bus Pitt would ride into West Virginia and told them stories of the team bus getting pelted with beer bottles and rocks on previous trips to Morgantown.

“I was just trying to tell our players, ‘We better get ready for what we’re driving into here. This is more than just a college football game,'” Wannstedt said.

Star running back LeSean “Shady” McCoy was ready.

“So we’re driving in on the bus, and it’s quiet,” Wannstedt recalled. “And all of a sudden … Bang! Bang! Here it comes. And Shady kind of stands up and says, ‘Hey, Coach, just like we saw on the tape!’ and then the whole bus just comes alive.”

Things were just getting started. On the first play of the game — a 12-yard run from McCoy — West Virginia defensive end Johnny Dingle and Pitt tackle Jeff Otah were called for personal fouls after getting into a scuffle after the whistle.

“Both these guys dropped their gloves and just started wailing on each other, and the whistles were blowing,” Wannstedt said. “And I’m standing on the sidelines, I ruptured my Achilles [a month earlier] and I’m on crutches, laughing to myself.

“I said, ‘Well, these guys get it. We are in the Backyard Brawl.'”

TO UNDERSTAND THE passion of the Backyard Brawl, one must understand the region and demographics in which the age-old rivalry exists. The teams first met in 1895 but, largely because of conference realignment, the game has been on hold since 2011. It returns Thursday night in Pittsburgh (7 ET, ESPN and ESPN App), and the intensity that built up over 104 meetings (Pitt leads 61-40-3) can’t be erased by an 11-year pause.

West Virginia’s in-house historian, director of athletics content John Antonik, gives a fair, overhead description of the rivalry.

“The thing is, we’re all basically the same people,” he said. “The people in West Virginia are coal miners, and a lot of the people that supported Pitt are steel workers. So you’ve got the mills and the mines. So from that respect, it’s similar. But culturally, [Pitt] is an urban campus, West Virginia’s a rural campus, even though we’re only 75 miles away.

“You know, the way it was portrayed to me from the people in Pittsburgh, the Pitt people always viewed Penn State as the game that they wanted to win most. West Virginia was the game they didn’t want to lose. There’s a big difference there.”

Former Pitt sports information director Sam Sciullo doesn’t disagree. “Pitt fans look at West Virginia as more of a nuisance or an annoyance. Like a little gnat flying around your ear when you’re in bed in the summer,” he said.

“Pitt just thinks they’re better than us,” added former West Virginia quarterback Marc Bulger.

Not surprisingly, there’s no lack of ill will between the two sides. That has been clear pretty much anytime Pitt has ridden into Morgantown.

“They may be beating on the bus, they may be rocking the bus or they may be throwing stuff at the bus,” said Jackie Sherrill, Pitt’s head coach from 1977 to 1981.

“[Former Pitt head coach Johnny Majors] used to tell us to keep our hats on because some projectiles are going to be coming down,” said Tony Dorsett, who played at Pitt from 1973 to 1976. “You didn’t know what was going to happen.”

Thirty-one years later, in 2007, the Panthers and freshman quarterback Pat Bostick rode into Morgantown and had nearly the same experience.

“We did not get nickels and quarters and dimes thrown at our heads … but we did have full beer cans thrown at our buses. We did have men, women, children, flipping us the bird, saying, ‘Eat s—, Pitt!’ All those things were real,” he said.

The hate for Pitt is engrained early for those in Morgantown. “Any good West Virginia parent that’s a WVU grad raises their kid to be able to say ‘Eat s—, Pitt’ during ‘Sweet Caroline,'” Antonik said of the Neil Diamond anthem.

The most common retort from the Pitt faithful to Mountaineers fans is to make references to West Virginia being from “the country.” The most infamous example of that came in 1994.

During the game, Pitt public address announcer Don Ireland made several announcements making fun of West Virginia. In one, Ireland said there was a tractor in the parking lot with its lights on with a West Virginia license plate that read “EIEIO.” He also said the stadium’s smoking ban included corn-cob pipes.

Bulger, the former Mountaineers QB who grew up in Pittsburgh, said his first memory of the Backyard Brawl was hearing Ireland make the “EIEIO” crack, which caused a bit of a firestorm. Pitt athletic director Oval Jaynes apologized to West Virginia officials for the announcements by Ireland, who briefly resigned in the aftermath but was reinstated.

“Looking back, I go, ‘That’s so disrespectful.’ And we’re 70 miles from Morgantown,” Bulger said. “I’m [from] inner-city Pittsburgh. We’re not far; we’re the same people. I don’t get the whole redneck thing. That’s the thing that bugs me the most.”

The intensity of the rivalry can lead people to do things they typically wouldn’t.

Sherrill always had a priest travel with the team to lead the Lord’s Prayer and give a blessing on the road. The 1977 trip to Morgantown was no different.

“So he called everybody up and they said the Lord’s Prayer and gave a blessing,” Sherrill said. “And the nickname of West Virginia at that time was ‘the snakes’ — that was what the Pitt people called West Virginia. And shortly after he gave the blessing, he said, ‘OK, laddies, now’s the time to go out and kick the s— out of the snakes.’ The players looked at each other. They couldn’t believe that he said it.”

Pitt won the game 44-3.

The proximity of the schools, which are a little more than an hour’s drive apart on Interstate 79, adds fuel to the fire.

“Part of the interesting dynamic is, if you go to West Virginia, you go to Pitt, you’re getting recruited by both schools for the most part, whether you’re from Florida, Texas or Pittsburgh,” Bostick said. “So our coaches knew their players, their coaches knew our players.

“[In 2007] Vaughn Rivers fumbled a kickoff return, Lowell Robinson stripped him. And I remember a coach of ours talking to Vaughn on the sideline, saying, ‘You should have come to Pitt — this wouldn’t have happened.'”

The recruiting wars caused some hard feelings and put a chip on many shoulders.

Bulger went to Central Catholic High School, less than a mile from the University of Pittsburgh. Dave Havern, Bulger’s quarterbacks coach at Central Catholic, ran into a Pitt assistant coach one day and tried to convince him to take a look at Bulger.

“I said, ‘Listen, dude, what’s up? I mean, you could walk down and see this kid,'” Havern said. “I said, ‘He’s really good! And I’m not just saying that. I mean, you know, I want you guys to do well.’ So they said, ‘We don’t think he’s a D-I player.'”

“It wasn’t Johnny, me and Coach Majors became friends after,” Bulger said, “but his coordinators told me I wouldn’t play Division II, let alone Division I. And I said, ‘OK.’ Coach [Don] Nehlen came in and wanted me and so I went down there.”

Despite Nehlen giving Bulger a chance at West Virginia, the QB had one gripe with his coach.

“Coach Nehlen was the best ever. I love the guy,” Bulger said. “I’m just mad he pulled me in the third quarter. We’re playing in Three Rivers [Stadium] in ’98. I had six touchdowns. I wanted to get to like eight or nine, and after the third quarter he pulled me. I go, ‘I wanted to stay in!’ and there’s no way someone else is gonna throw nine or 10 touchdowns in a game, even nowadays. But he didn’t want to get me hurt because it was always a day after Thanksgiving and the bowl was coming.

“But I’d have loved to throw 10 TDs on Pitt, that’d have been so great … Because I knew the coaches were still there that told me I wasn’t good enough.”

THERE ARE GAMES that help define the rivalry. There are some that are simply great games. And then there are some that are both.

In 1955, West Virginia was 7-0 and ranked No. 6 in the country going into the Brawl before losing to Pitt, ruining the Mountaineers’ Sugar Bowl bid. The Panthers were selected instead.

West Virginia knocked off Pitt in what is known as the “Garbage Game” in 1961 after one of Pitt’s players said the Mountaineers were rebuilding their program with “Western Pennsylvania garbage.”

In 1975, Mountaineers walk-on kicker Bill McKenzie made the go-ahead field goal in the closing seconds to give West Virginia a win over No. 20 Pitt. As the Panthers were leaving Morgantown for the drive back to Pittsburgh, they could see couches being set on fire along the way.

“It was probably the biggest party Morgantown has ever had,” Sherrill said.

Pitt would get revenge the following season in a game in which Dorsett set off an actual brawl at the end.

“As the game went on, there were guys, you know, they’d tackle me and then be in the pileup pinching me, punching me, or in this particular situation was when they tackled me and the one defender as I was getting up, he pushed my head into the turf,” he said. “I lost it at that point.”

Dorsett was ejected for the first time in his college career. He would go on to win the Heisman Trophy that season and help Pitt win its ninth national championship.

In terms of capturing the intensity, passion and spirit of the rivalry, it’s hard to top 1970, when West Virginia opened a 35-8 lead in the first half.

“Everything that we did in the first half worked,” former West Virginia linebacker Tom Zakowski said. “We just scored touchdown after touchdown. Came in off the field at halftime in the locker room, you know, a lot of joy, a lot of happiness, a lot of back slapping.”

The atmosphere in the Pitt locker room, not surprisingly, was quite different, but not in the way one might expect.

“We went in at halftime and it was like, jeez. Nobody was yelling and screaming and the coaches weren’t berating us for the rotten half we had played,” then-Panthers quarterback Dave Havern said. “But I remember it was a kid, a guy John Stevens. He was a big defensive tackle from Sharon, Pennsylvania, up around Youngstown. And a big, tough guy, you know?

“So Stevens gets up and he’s a brawler, he says, ‘Hey, I do not give a damn what happens the rest of this half, but I’m beating the s— out of my guy.'”

West Virginia didn’t get a single first down in the second half, while Pitt switched to a Power-I offense and ran the ball the entire half, winning the game 36-35.

After the game, West Virginia fans were banging on the Mountaineers’ locker room door, furious at then-head coach Bobby Bowden.

Bill Hillgrove, who has been the voice of Pitt athletics since 1974, said, “The vivid memory there was that the press box had a microphone down near the locker room to get players’ quotes. And you could hear the West Virginia fans chanting for Bobby Bowden’s head because of the way the game went.”

“There are people alive today that remember that game that still are convinced that Bobby Bowden is a terrible football coach,” Antonik said. “From that moment on, nothing could convince them otherwise.”

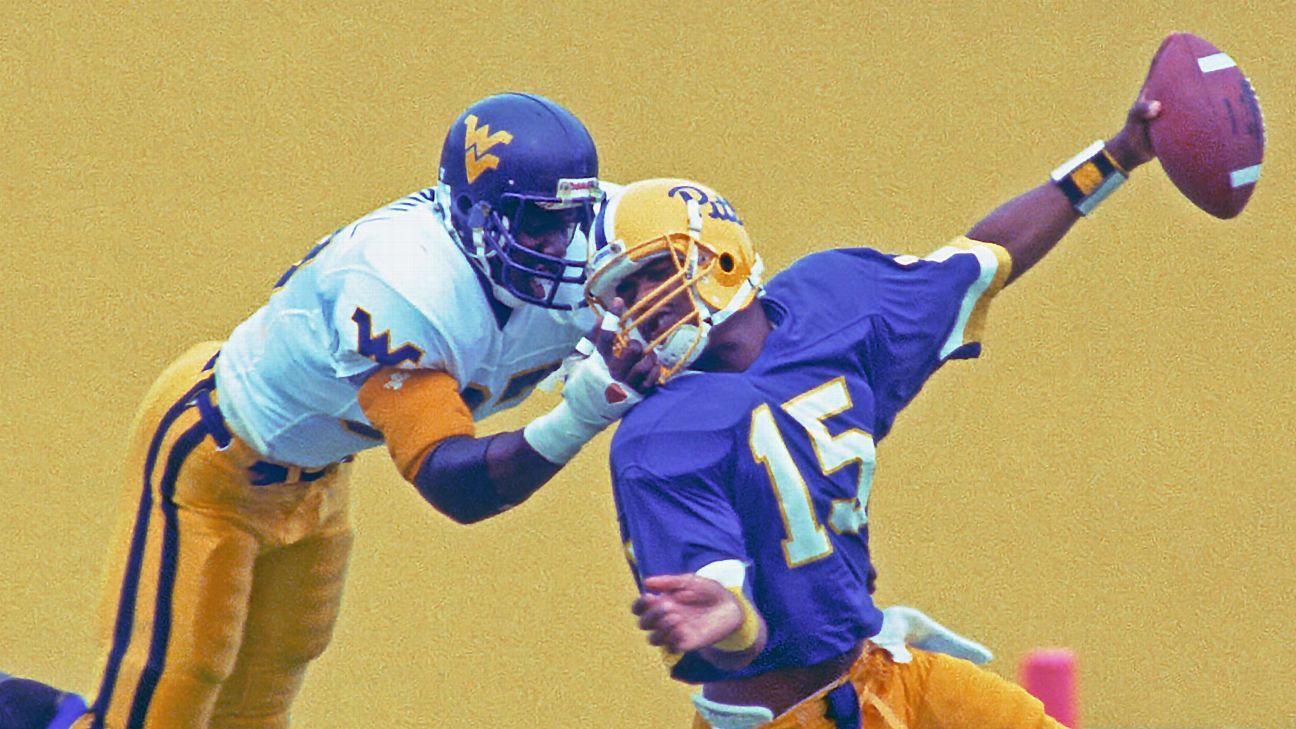

West Virginia had its own huge comeback in 1983. The year prior, No. 2 Pitt and No. 14 West Virginia played one of the rivalry’s biggest games from a national perspective, with Dan Marino sealing the Panthers’ win with a 6-yard touchdown pass with 3 minutes, 24 seconds to play.

West Virginia quarterback Jeff Hostetler had to be helped onto the bus after the game because of the physical play of Pitt’s ferocious defense.

Nehlen’s teams had been chipping away at Pitt since he took over in Morgantown in 1980, and while the Mountaineers came close in 1982, Hostetler helped him kick the door down in 1983.

“A lot of things were predicated on the year before,” Hostetler said. “That Pitt team had, I think, nine or 10 drafted players in the NFL — they were loaded. And that’s a game that we should have won, we had the opportunity. We played really well, and we let it slip away at the very end against an extremely talented team. And so that taste never left any of my teammates and I. We wanted this game.”

West Virginia trailed 21-17 with 12:27 to play and started what would be the game-winning drive on its own 10-yard line.

“I can remember getting into the huddle and saying, ‘Ninety yards. Here we go, guys. We’re going. We’re scoring,'” Hostetler said.

At one point during the drive, Hostetler scrambled out of bounds and was again hit by the Pitt defense that had tormented him the year before.

“The stadium was packed, the sidelines were packed,” Hostetler said. “I’m laying on the sidelines just having gotten hit, and all of a sudden I’m being lifted up by two or three guys. And I look, and they’re my brothers. Somehow they got down onto the field, and they’re yelling, ‘Back in there — let’s go, let’s go, let’s go!'”

Hostetler got up and finished the drive. With the ball on Pitt’s 6-yard line, Nehlen called for a bootleg that Hostetler said he had been asking for the entire second half.

“I knew it would work, and I couldn’t get Coach to call it,” Hostetler said. “And then we’re down there on the 6, and he calls it, it’s just like, ‘I know we’re scoring.’ It was an awesome, awesome feeling. Especially being at home, and especially against Pitt.”

Antonik said the game was a defining one for Nehlen’s tenure as Mountaineers coach.

“It snapped a seven-game losing streak,” Antonik said. “And from that point on, it completely changed. The whole balance of the series changed.”

Since the Hostetler-led, 24-21 comeback win, West Virginia leads the series 18-9-2.

“I think that in this rivalry to really get a full view and understanding of this game is when you lose it,” Antonik said. “That’s when you really feel the full effect of this football game.”

PITT WAS A four-touchdown underdog going into Morgantown in 2007. The week before, the 10-1 Mountaineers put up 66 points and 624 yards against No. 20 UConn. The final game of the regular season was expected to be a tuneup.

In the week leading up to the game, Wannstedt was concerned with how the Panthers were practicing defensively.

Standing with offensive coordinator Matt Cavanaugh, Wannstedt looked over to the defensive side and saw the team doing tackling drills. More time passed, and about halfway through the practice, Wannstedt looked over again. The defense was still doing tackling drills.

“Paul Rhoads was our defensive coordinator,” Wannstedt said. “So I walk over, I say, ‘Paul, come here. What are we doing?’ And he says, ‘Coach, the more film I look at, if we don’t tackle these guys, it don’t make any difference what scheme we have. We can’t stop them. They’re that athletic and that fast.’

“Long story short, at the end of the game, we had eight missed tackles for the entire game. In years past, we would have eight missed tackles on one play.”

The game went exactly the way Pittsburgh needed it to in order to win — five West Virginia turnovers, a thumb injury to Mountaineers quarterback Pat White, two missed kicks by WVU’s Pat McAfee. Pitt was able to stick to its game plan and not ask too much of Bostick, giving McCoy as many touches as possible.

Pitt won 13-9, and West Virginia’s chance to play for the national championship was lost.

“You know how when people go through like traumatic instances and they kinda try to forget everything that happened around it?” White said. “Other than me dislocating my thumb and the last play of the game, I couldn’t tell you what happened. I’ve yet to watch it. I don’t know if I can.”

“They already had the banner hanging out in front of the Hilton down in New Orleans,” Wannstedt said. “‘Welcome Mountaineers!’ They were gonna play the national championship game. It was done.”

“I remember postgame,” Bostick said. “I’ve never been in a locker room like that. You could hear us in (then-West Virginia coach) Rich Rodriguez’s press conference. Like they’re on lockers, there are guys crowd surfing. There’s so much that night that’s such a blur. Because, you know, for me, it was gonna be the culmination of a pretty tough season. But it just happened and was one of the things that you could not have predicted would happen.”

On the other side, Rodriguez and his team were in shock.

“I had a very brief talk with them and then went back to the coaches’ locker room — and puked a little bit,” he said.

THE BACKYARD BRAWL was traditionally played on the Friday after Thanksgiving. This season, the game will serve as college football’s opening act for Week 1.

Both head coaches and their players will be getting their first taste of the Brawl. West Virginia coach Neal Brown said just because this year’s game is different than in years past, that doesn’t make it any less meaningful.

“You start thinking about it, we’re a pretty young team,” he said. “Our guys were 8, 9, 10, 11 years old last time this game was played, so there’s not a whole lot of recall, even from the guys that are from the state of West Virginia. …

“But man, you want to bring out real passion in the West Virginia fan base — our alumni or our former players — you talk about the Backyard Brawl, and you get it. You play ‘Sweet Caroline’ one time at a West Virginia event, and then you get an idea of what this rivalry means. So the importance of the game is not lost on myself or our team or staff.”

Pitt head coach Pat Narduzzi said, “The people that were here 10 or 15 years ago that got spit on, they got rocks thrown or beer dumped on them, those are people that really get into rivalries. But I know enough about rivalries that I want to embrace it for our kids because it’s important to us. And if it’s important to our fans in the Panther nation, it’s important to me. That’s what we do, is go fight for each other, and so that’s what it’s all about.”

West Virginia redshirt senior wide receiver Bryce Ford-Wheaton will become the third generation in his family to participate in the Brawl. His grandfather played in it in the 1960s, and his uncle played in it in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

“I just never really actually thought I’d have my own crack at Pitt,” Ford-Wheaton said. “So for it to come full circle — I just remember all the brawls during the game or the fights I would see, the chippiness and, I mean, there’s really a hatred for Pitt. So just to finally experience that myself and be able to play in the game is going to be a crazy thing.”

West Virginia senior defensive lineman Dante Stills, whose father played in the rivalry in the mid ’90s, said, “My dad told me it’s a rough game, it’s gonna be back and forth, it’s gonna be very physical. So I’m just getting that mindset where I’m just going to lay down on the line.”

Pitt and West Virginia have a home-and-home agreement that runs through the 2025 season, with Pitt hosting this year and 2024. After a three-year hiatus, the teams are scheduled to meet each season from 2029 to 2032.

While that’s all well and good for the fans, the players’ primary focus remains Thursday night.

“So many people are so passionate about it, when people talk about it, I feel it in their voices,” Pitt redshirt senior defensive lineman Deslin Alexandre said. “I think it’s big for Pittsburgh, it’s big for West Virginia just to have this Backyard Brawl back.”