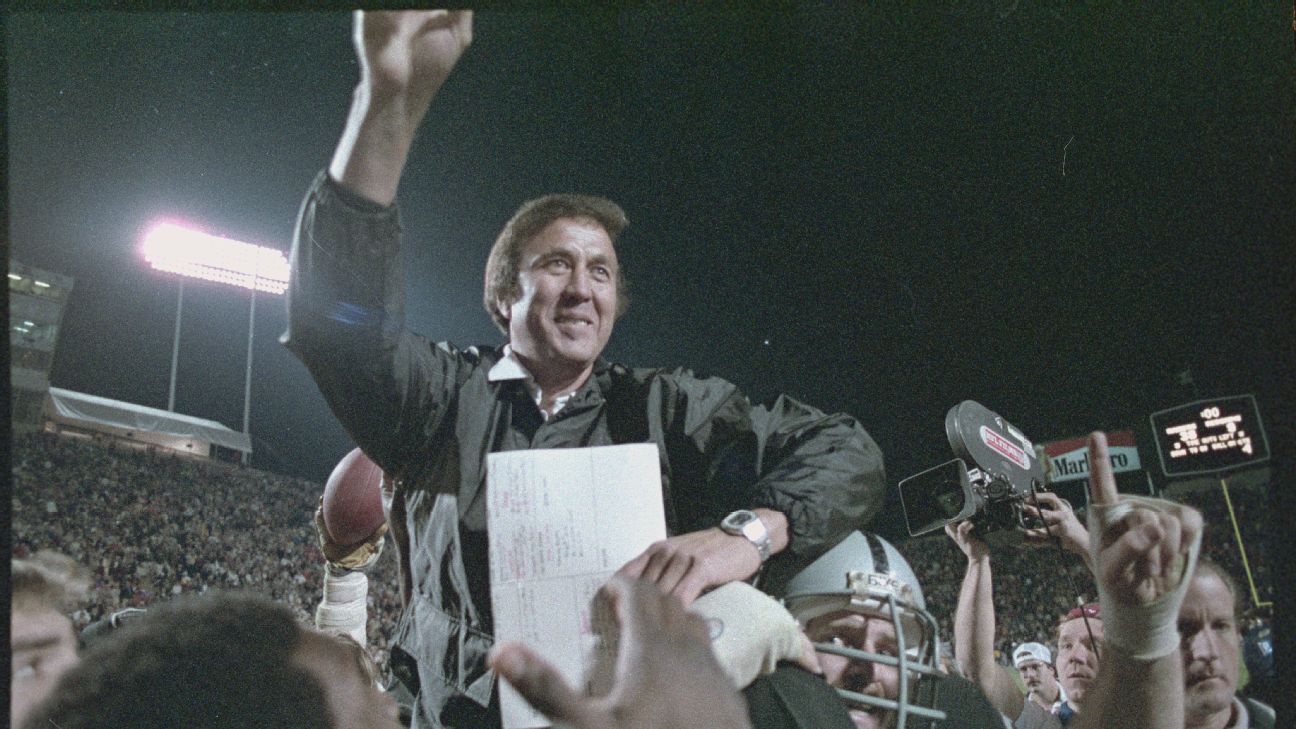

“You have to be happy for that man. Talk about Cinderella stories — Chicano, worked at six, seven years old in the fields, became a fine athlete, on to Pacific, had a fine pro career and now, maybe the most important moment in his life.” — Dick Enberg, as the camera zoomed in on Raiders coach Tom Flores in the closing minutes of NBC’s broadcast of Super Bowl XV on Jan. 25, 1981.

LAS VEGAS — It was during the Raiders‘ run to a Super Bowl XVIII title, some three years after Enberg’s soliloquy, when a pre-teen Danny Gonzalez noticed something about the stoic coach on the sideline wearing Silver and Black.

He looks like us.

The Albuquerque-born and raised Gonzalez, who would grow up to become the head football coach at his hometown University of New Mexico, had a cousin named Casey Flores.

He sounds like us.

So, of course, the playful name-claiming began when it came to Tom Flores, the pioneering coach of the Raiders who was on his way to winning his second championship in four years, the fourth Super Bowl ring of his career.

“We used to say he had to be related somewhere down the line,” Gonzalez recalled with a laugh. “We acted like Coach Flores was his uncle.

“He was Hispanic, like us. We were ecstatic that one of us was not only leading the Raiders, but winning Super Bowls. He was just like us. That’s what we used to always say. He was just like us.”

He is one of us.

With Flores being inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Aug. 8, there is a renewed sense of dignity bubbling in a small, but fiercely proud and growing community — Latino football coaches.

Entering the 2021 college season, there are seven Latino head coaches in Division I — Oregon’s Mario Cristobal, Baylor’s Dave Aranda, Miami’s Manny Diaz, Virginia Tech’s Justin Fuente, Boise State’s Andy Avalos, UNLV’s Marcus Arroyo and New Mexico’s Gonzalez — according to Dr. Mario Longoria, who has authored a pair of books on Latinos in football. And the ranks are swelling in high schools.

Particularly in the South. And Flores’ Hall induction can only help.

“It’s quite an honor, Mexicanos are overjoyed,” Longoria said. “The question, after all the celebrating and patting on the back, is this — what took so long? They know the answer. But because [Flores] had to overcome additional barriers that others didn’t because they were privileged, that’s what makes it more special.

“He led. He led by example. A guy that would inspire and do well and succeed.”

Added Armando Jacinto, president of the Hispanic Texas High School Football Coaches Association, which began as a group chat but now has 732 members: “It’s far overdue, but I don’t want to haggle because it happened. It happened. It’s an inspiration for Hispanic coaches and Hispanic people as a whole. We have the acumen to achieve these things, even if there are few and far between. It’s not a long list.

“We’re cleaning the building. We’re building the building. We’re even driving to the building. But we’re not running the building. I’m not demeaning those jobs, because they are important. But no one that was calling the shots looked like me.”

Before Flores was hired by Al Davis in 1979, Tom Fears was the first Hispanic coach in NFL history, hired by the expansion New Orleans Saints in 1967. Ron Rivera was next after Flores, with the Carolina Panthers in 2011. He is now with the Washington Football Team, and Brian Flores is entering his third season with the Miami Dolphins

Tom Flores, though, was not only the first minority coach to win a Super Bowl (he won two), he was also the first Latino quarterback in pro football history (1960 with the Raiders) as well as the first minority general manager (with the Seattle Seahawks in 1989).

It was Flores’ past as a quarterback, though, that initially got Rivera’s attention. Even though Rivera went 2-0 against Flores the coach as a linebacker for the Chicago Bears, beating him as a rookie in an infamous 1984 game at Soldier Field and in Flores’ final game as Raiders coach in 1987.

“It’s awesome,” Rivera said of Flores’ Canton call. “A lot of us are getting in the ranks and for somebody who had a great career and is an iconic figure in our community, that’s outside of the box.

“He was truly an individual toeing the line. We represent so many people.”

Rivera said he was having dinner with his wife and his brother’s family in California this offseason when Latino fans approached his table. They recognized Rivera as a trailblazer. They were also huge Raiders fans, in part, due to Flores’ impact.

“That’s the deal,” Rivera laughed. “I get it. I appreciate it. But that shows the inspiration he’s provided through the years. The guy said he was coaching Pee-Wee football and was inspired by me. I was inspired by Coach Flores.”

What Flores meant and represented to a certain community did not truly hit him until he had a similar encounter with a fan.

“One guy told me, ‘When you won your first Super Bowl, my father cried,'” Flores recalled in the upcoming book “If These Walls Could Talk: Stories from the Raiders Sideline, Locker Room and Press Box.”

“And I said, ‘Do I know you?’ ‘No.’ ‘Then why did he cry?’ ‘Because you’re Latino.” I was kind of taken back by it. He was so proud, and I didn’t know this kid. I didn’t know his dad. But he said he was so proud because, ‘Of what you had done, and you’re a true Latino.’ So it made me feel good, but it also made me aware of some other things in life that are happening…especially in the minority world. And I was one of a very small few Latinos in the world of football. And I was first in many things, very proud of that.

“Al gave me a big boost when he hired me as a head coach. And then Ken Behring and Ken Hofmann hired me as a general manager up in Seattle and gave me a chance as a Hispanic to run a team, one of 32 teams in the world. And that kind of went unnoticed. There wasn’t a lot of hoopla for the Hispanics. And there still isn’t that much, but little by little. There again, it’s a slow process. A lot of these things don’t happen overnight because we cannot allow ourselves to have setbacks like we’ve had the last four years.”

Rivera’s conversations with Flores have been just as illuminating and inspiring.

Flores, who went 91-56 with the Raiders, 8-3 in the playoffs, was a combined 21-15 against coaches already voted into the Hall of Fame. Among them: 6-1 vs. Don Shula, the NFL’s all-time winningest coach, 3-1 vs. Chuck Noll and 2-1 vs. Bill Walsh and Bill Cowher. Flores was also 11-5 vs. Don Coryell, who was a Hall finalist with Flores in 2019.

“I thanked him for carrying the mantle as a forefather,” Rivera said. “He told me, ‘Just know, you’ve got to carry the mantle now.'”

It’s a familiar refrain that’s trickling down to college, where just 2.7% (417 of 15,710) of Division I FBS players identified themselves as Hispanic or Latino in 2018-19, per USA Today and the TIDES College Sport Racial and Gender Report Card (eight of 1,357 players identified as such in the NFL in the same year, or 0.5%).

Arroyo, who grew up near Sacramento, was a year and two days old when Flores’ Raiders won Super Bowl XV. Avalos, who grew up in the Southern California town of Corona, was born four days after Flores’ defending Super Bowl XV champs beat the New England Patriots on Nov. 1, 1981, to improve their record to 4-5.

“One guy told me, ‘When you won your first Super Bowl, my father cried. And I said, ‘Do I know you?’ ‘No.’ ‘Then why did he cry?’ ‘Because you’re Latino.'”

Tom Flores, recalling a conversation with a fan

Neither had real memories of Flores on the Raiders sideline, but they have both been inspired on their respective coaching journeys.

“Growing up, you have these certain family conversations where that dialogue is instilled in you and you hear about ‘race and minority’ and how you want to put yourself in a position to break barriers, in whatever career path you choose,” said Arroyo, a board member of the National Coalition of Minority Football Coaches’ Coalition Academy.

“With Tom, as a coach, he was no different to me than Bill Walsh. But that guy looks like me. He has an ‘R’ in his last name. You can roll that ‘R’ like you can in my last name. There’s a little bit of me there so there’s a pride and a respect.”

Avalos said Flores was the reason he was a Raiders fan growing up and said meeting him and picking his brain was on his bucket list.

“Not only for his accomplishments, but as a person,” Avalos said. “Not a lot of opportunities for coaches at the level he was at. He definitely provides inspiration and a confident stride.

“He was a role model of mine at a young age. It provides the youth and the middle-aged a perspective that we can accomplish whatever we want.”

Again, from Flores’ perspective, he was just playing and coaching a game he loved. And winning. And unbeknownst to him at the time, inspiring future generations.

Survivor? It’s in Flores’ blood. His forebearers had to fight off Pancho Villa’s bandits in the aptly named town of Dynamite in the Mexican state of Durango. And despite missing the 1962 season with tuberculosis, Flores, who was one of 11 quarterbacks on the first day of the first Raiders training camp in 1960, is the fifth-leading passer in AFL history with 11,959 yards and won his first ring as a backup with the Kansas City Chiefs in Super Bowl IV.

His second ring came as an assistant on John Madden’s staff for Super Bowl XI and it was Flores who, as the team’s receivers coach, phoned down from the press box to call “Ghost to the Post” in the 1977 playoffs.

“When you make the Hall of Fame, you don’t make the Hall of Fame,” Flores said recently. “You and your family make the Hall of Fame. And your friends and your coaches and your players. We all go in together. I’m just a representative of a wonderful group and a wonderful game.”

Gonzalez, who said he was “awestruck” the one time he met Flores at a coaches convention in the late 1990s, thought “We can do it,” after that meeting. Meaning, succeed in coaching football.

And when word filtered out in February that Flores, who turned 84 in this year, had been selected for enshrinement after missing out the previous two years as a finalist, Gonzalez had a phone call to make.

His cousin Casey had passed away in 2013, so Gonzalez dialed Casey’s mother.

“It was a bigger deal because, like I said, he was one of us,” Gonzalez said of Flores being elected. “I just told my Aunt Cindy, ‘I’m sure Casey is up there smiling.”

He’s not the only one.