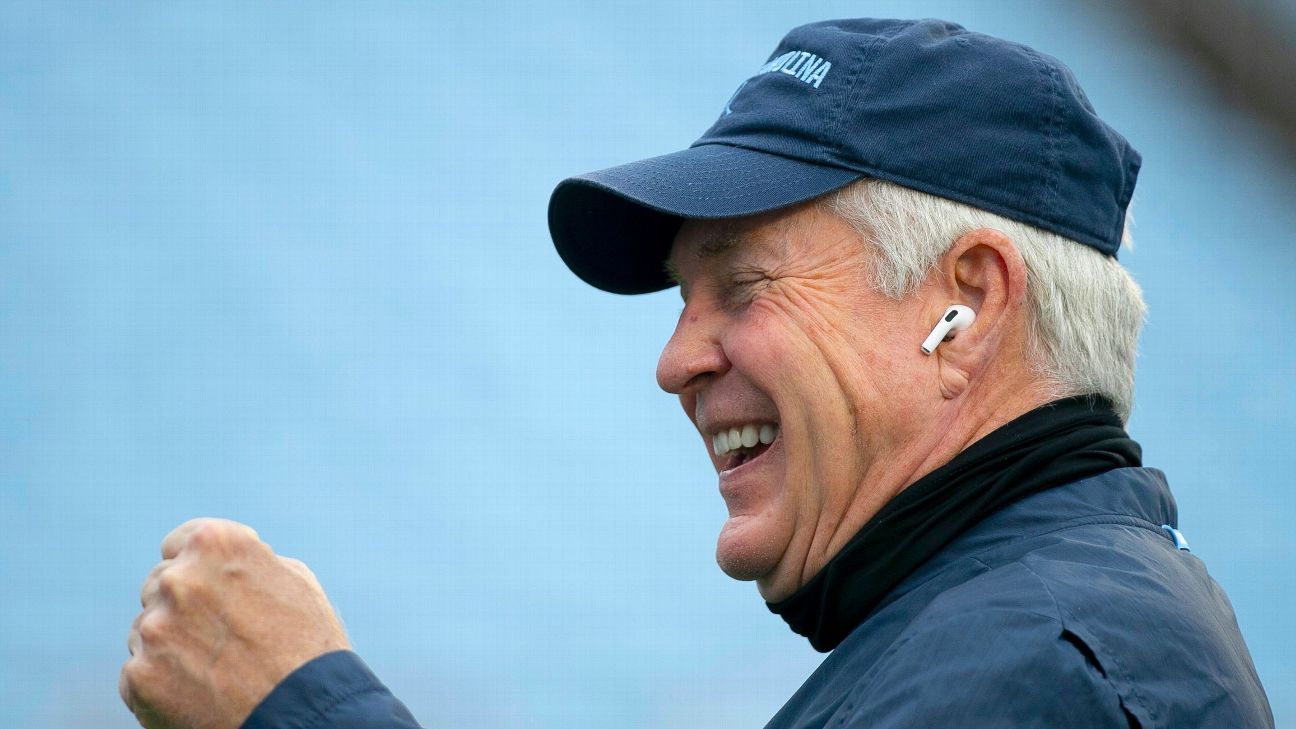

Not long after Mack Brown was hired at the University of Texas, he was saved from the first controversy of his young Longhorns career by the unlikeliest of allies.

In 1998, Brown and longtime Texas A&M coach R.C. Slocum were guests at a public event in San Antonio along with former Texas A&M and Alabama coach Gene Stallings.

Both Slocum and Stallings were well-versed in the importance of hand signs in Texas college football. Brown, a Tennessee native who had just arrived from North Carolina, got a quick lesson.

“I didn’t know much about the history of the two places, and a fan walked over and stood between the three of us and said, ‘Let’s take a picture,'” Brown recalled to ESPN recently. “He held up his thumb and so did R.C. and so did Coach Stallings. So I held mine up. R.C. grabbed it, threw it down and said, ‘Boy, you’re gonna be fired before you ever coach a game if you throw that up. You need to learn very quickly that you Hook ’em, you don’t Gig ’em.'”

For Brown, it was the beginning of what would be a very cordial relationship with an ordinarily hostile neighbor. So when North Carolina faces Texas A&M in its first-ever appearance in the Capital One Orange Bowl on Saturday (8 p.m., ESPN/ESPN App), Brown won’t be seeing red when he looks across the field and sees maroon. In a sport where fans often wish the very worst upon their nemeses, Brown always killed ’em with kindness.

“I’ve never been a guy that hated our rivals,” Brown said. “I’ve always liked our rivals. They’re two great programs in a state that cares about football, maybe more than any other state in the country. It’s because it’s like a religion there, and both programs are so good. I would never say anything bad about Texas A&M.”

Brown announced his arrival in the rivalry with a 26-24 upset of the No. 6 Aggies in 1998. Over the final 14 years of the series before Texas A&M left for the SEC, Brown beat the Aggies 10 times, going 4-1 against Slocum, 3-2 against Dennis Franchione and 3-1 against Mike Sherman, including the final 27-25 win in 2011.

“Mack viewed rivalries as about pride,” said Ricky Williams, who won the Heisman Trophy in Brown’s first season in Austin after rushing for 259 yards in that upset win over A&M. “So the idea of beating the Aggies was about showing that we’re the best team in Texas. He saw those big games as huge opportunities for us.”

Brown never took shots, fired insults or came up with gimmicks to refer to A&M. His magnetic charm that remade the recruiting landscape in Texas also often made it sound like he was rooting for the Aggies — other than in one game, of course.

“We don’t need for A&M to have a bad team,” Brown told the Austin American-Statesman’s Kirk Bohls before his first matchup with the Aggies in 1998. “If we’re both 6-4 coming into this game, that would not help either one of us.”

Brown insists that none of this is a put-on, another recruiting pitch by a wily coach. He and Slocum were good friends dating back to when he was an assistant to one of Slocum’s good friends, Donnie Duncan, at Iowa State from 1979 to ’81. Brown’s longtime offensive coordinator, Greg Davis, who worked for Brown at Tulane and Texas, got his first college job at Texas A&M at the urging of Slocum.

“I was with [Brown] 18 years, and it was never about him vs. R.C. or him vs. whoever,” Davis said. “Obviously it was an important ballgame. But it was never a personal deal with him.”

Brown even allowed Slocum to arrange a tour of Texas’ facilities for A&M officials when Slocum felt that the Aggies were falling behind in the arms race. There was always a mutual respect for each other and for the programs.

“It was much different than the Oklahoma rivalry,” Brown said last week. “The Oklahoma rivalry was state versus state. The A&M rivalry was family vs. family. They were all Texans, and even at the game you would see scattered fans with different colors and family sitting together. I used to sit as a kid and watch Texas and Texas A&M [on TV]. It highlighted high school football and high school football coaches in the state of Texas to everybody in the country.”

Dave South called Texas A&M football, basketball and baseball games for 33 years and was honored in 2018 with the National Football Foundation’s Chris Schenkel Award for excellence in broadcasting. While in New York for the induction, he ran into Brown, who was being inducted into the NFF’s Hall of Fame the same year, and he was surprised by Brown’s revelation when he introduced himself.

“I know who you are,” Brown told South. “When I was traveling, a lot of times when we didn’t have a game or we played in the afternoon and you guys played at night, I would listen to you.”

South said Brown had nothing but kind words for his former foe.

“When the game was over, the game was over,” South said. “He was very complimentary of A&M and the rivalry.”

But nothing showed Brown’s true respect for the Aggies like his final news conference upon resigning at Texas in December 2013, when Brown took time to remember the Aggie bonfire collapse in 1999 that killed 12 students.

Following Brown’s initial statement, a reporter asked if there was anything he would have changed about his 16 years in Austin. He first said he would give anything to have Cole Pittman back, referring to the UT defensive tackle who died in a 2001 car accident. Then came a remarkable off-the-cuff moment for a Texas coach going through one of the worst professional days of his career.

“And I would want the bonfire [collapse] to not have happened at A&M,” he said. “Those are two horrible things in my life that I will never forget. Playing A&M on Thanksgiving, I thought about the families. … When you lose your children, there is nothing worse than that in the world. I think about that every Thanksgiving because there are 12 families that don’t have a good Thanksgiving. That’ll never go away.”

At the Orange Bowl news conference, he again vividly recalled the week of the tragedy.

“I thought we probably shouldn’t play the game,” he said. “I told R.C., whatever you all want we’ll do. Not only did we play the game, but I think we were ahead 16-0 at halftime, [and] they came back and beat us 21-16 right at the end. I’m not sure that it wasn’t best for them to have won that game.”

Davis remembers Brown being deeply affected.

“He was shook up at the bonfire,” Davis said. “In fact, we had a blood drive in Austin at the football office and most of the coaches gave blood.”

For Brown, the tragedy was perspective on what a rivalry really meant.

“I thought R.C. handled that situation better than anybody possibly could,” he told ESPN last week. “We had the memorial with a lot of students and fans from Texas A&M, which was a night that I’ll remember for the rest of my life. Even the game, our band playing ‘Amazing Grace’ and everybody in that whole stadium mourning for those families. … That’s when you know it’s much bigger than some football game.”

There’s no doubt that Brown wants to beat A&M to put the finishing touches on a remarkable turnaround season at North Carolina, which is 8-3 after going 2-9 two years before Brown’s arrival.

Williams said Brown will sell this as another big-game step for North Carolina, “because of the success that A&M has had, because they’re from the mighty SEC,” he said. “When it’s a prime-time ballgame he knows that it’s a huge opportunity for his program to take themselves to the next level.”

“I’m sure he’s excited because he knows what kind of program [A&M has] had historically and the job that Jimbo [Fisher] is doing,” Davis added. “But it’s an excitement. It’s not in any way a revenge deal or anything like that. I certainly don’t think he will approach it any different than if he was playing anybody else in terms of the ol’ Aggies or whatever.”

And no matter how many nice words Brown says about the Aggies, there’s no doubt they want to beat him, too. But the absence from the rivalry may have even shined up Brown’s glowing words even more. Good luck getting him to say anything else.

“Texas A&M is one of the best programs in the country, and I always love going to play them at College Station,” he said. “Those fans are unbelievable. The place is as loud as anyplace I’ve ever been to coach against. The loyalty of those fans is just amazing to me.”