THE MOVIE THEATER was empty when the Chicago Bulls walked in.

It was Nov. 23, 1995, and the Bulls, in Salt Lake City to face the Utah Jazz the following night, decided to catch the 5 p.m. showing of “Casino” after the team’s Thanksgiving feast.

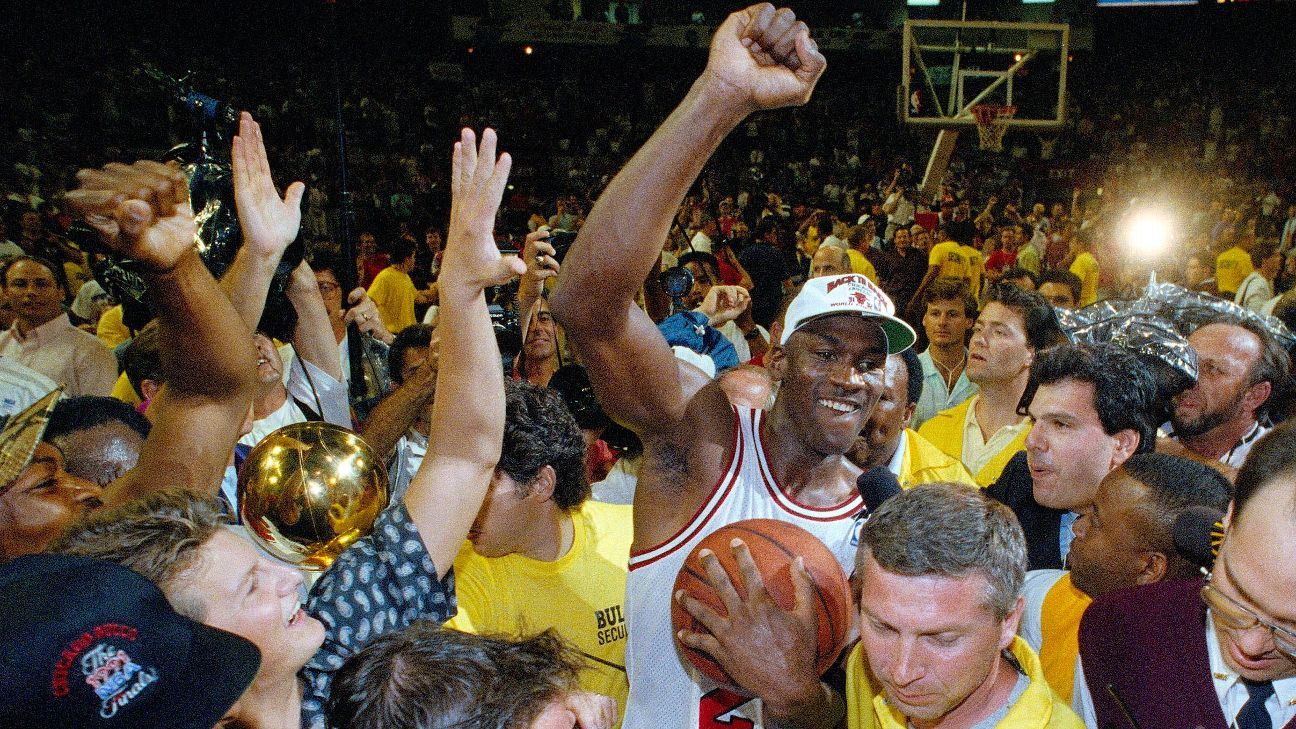

By the time they left the three-hour movie, a holiday crowd had packed the multiplex. It didn’t take long to notice the real attraction: Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen, Dennis Rodman and the other players exiting to walk back to their nearby hotel.

The Bulls quickly realized their party was growing exponentially.

“Everybody that was in the theater in line walked back to the hotel with us,” former center Bill Wennington said. “And Luc [Longley], myself and Toni [Kukoc] ended up being security to keep people away from Michael, Scottie and Dennis. It was crazy.

“Michael had his [security] guys there, but there was that many people,” he added of the need for his teammates to double as bodyguards. “We are talking a thousand people left the theater and followed us. In Utah.”

When you think of those Bulls, Jordan, Pippen and Rodman are on the marquee. But there were others — such as Wennington, Scott Burrell and Dickey Simpkins — who had front-row seats to the biggest blockbuster the NBA had ever produced.

Those former teammates have been texting and reminiscing with each other after every new episode of “The Last Dance.”

“There was almost a mythical quality to a famous team or an athlete like Michael back then,” former Bulls guard and current Golden State Warriors coach Steve Kerr told ESPN’s Scott Van Pelt on SportsCenter. “Nothing was left to the imagination.

“Nothing is left to the imagination now.”

SCOTT BURRELL ARRIVED at Chicago’s practice facility, the Berto Center, every day with fear lurking in the back of his mind.

The newest player during the 1997-98 season wasn’t scared of guarding Jordan in practice every day. That was expected. It was the unexpected that was inducing his anxiety.

“You are so afraid to hurt him,” Burrell said. “Say you bump knees [or] do something to his ankle? You’re the a–hole for the rest of your life.

“You didn’t want to be the guy to ruin three championships in a row or to end Michael’s career.”

The backup guard didn’t alter history, but as the documentary has shown, Burrell was the sacrificial lamb placed in front of an ultra-competitive Jordan every day.

“Hey, Scott Burrell!” he recalled Jordan saying as they stretched before the first practice of training camp. “You thought the best part of your trade was that you don’t have to guard me anymore.

“But now you have to guard me every day.”

With that, Jordan began a season-long onslaught of hazing, testing Burrell as if the Bulls’ championship odds depended on it.

After a practice in Denver, Burrell challenged Jordan to a one-on-one match to seven points. Burrell was leading 6-5 when he claimed he was fouled. Jordan did not acknowledge the call, Burrell said, and instead scored two straight baskets to win the game.

Feeling robbed, Burrell challenged Jordan to a rematch.

“What?” Jordan responded to Burrell. “Why would I play you? So you can tell your kids, ‘I beat Michael Jordan’?

“If I tell my kids, ‘I beat Scott Burrell,’ they’ll slap me in my face.”

Burrell never took Jordan’s belittling personally. Even now, Burrell says he cherishes every moment of what felt like a fantasy playing with Jordan and an all-time dynasty.

“It was like traveling with The Beatles, Jay-Z and Beyoncé,” said Burrell, who is now the head coach at Southern Connecticut State. “It was unbelievable. Every hotel we went to was mobbed by people. Every time you went to a game, you saw home and visiting fans line the streets trying to get a picture or glimpse of Michael.”

LATE IN HIS rookie season, Dickey Simpkins was dozing off in the practice facility lounge when he heard someone entering the Berto Center.

“What’s up, young fella?” Simpkins heard a familiar voice say. Half asleep, Simpkins rolled over to see who had greeted him.

“That wasn’t MJ,” Simpkins thought to himself. “Couldn’t have been MJ.”

When Simpkins later walked into the training room, he indeed found the Bulls legend catching up with former teammates.

Simpkins had never played with Jordan to that point — the star had retired a month before Simpkins’ NBA debut in 1994. Now, Simpkins was hoping this Jordan sighting was the first sign of a return.

Jordan didn’t practice that day, but soon after, coach Phil Jackson told the Bulls to keep the biggest secret in the NBA “hush hush”: A comeback was imminent. Jordan sent his famous “I’m back” fax on March 18.

“The greatest player to ever play the game was coming back to play,” said Simpkins, now a scout for the Washington Wizards. “And everything went from zero to 100.”

Simpkins won three titles with the Bulls, but the third seemed anything but assured. Before the start of the 1997-98 season, Simpkins was traded to the Golden State Warriors for Burrell and made his way back to Chicago in March after being waived. That odyssey gave him more of an appreciation for his close-up seat in Utah for Game 6 of the 1998 NBA Finals.

With 23 seconds left and the Jazz clinging to a one-point lead, John Stockton threw the ball inside to Karl Malone on the left block in front of Simpkins and the Bulls’ bench. As Malone posted up on Rodman, Simpkins could sense that Jordan was going to manufacture something.

Simpkins’ role in practice was to emulate Malone on the scout team, run his part of the Jazz’s famed pick-and-roll and occupy the spots on the floor the Utah power forward preferred. After a recent “The Last Dance” episode, Simpkins texted to check on Jackson, who replied by telling the forward that he was “an amazing Karl Malone.”

Simpkins’ gut was right. Jordan came over from the blind side, stripped the ball, then sank the series-winning shot.

“That is why he’s MJ!” Simpkins yelled to teammate Randy Brown as they sprang off the bench to congratulate Jordan during the ensuing timeout. “That is all I could think about when he hit that shot.

“Like, who could write that story?”