With “The Last Dance” debuting in 48 hours (!!!), let’s lead off this edition of 5 Things with some Chicago Bulls talk.

1. The Bulls’ biggest issue

Chicago’s decision to move on from Jimmy Butler when he was not even 28 stands as one of the bolder, maybe even dangerous, franchise pivots of the last decade-plus. The Bulls could have continued with Butler — then and perhaps still a borderline top-10 player — Nikola Mirotic, cap room in one or both of 2017 and 2018, and all their own draft picks. (Superior roster management before then would have made that path not taken even more attractive.)

Instead, they bailed out, fearing a supermax for Butler and wagering a teardown would give them better championship odds in the early/mid-2020s. In return, they received Zach LaVine, Kris Dunn, and the right to move up nine picks for Lauri Markkanen. The trade also set them up to be bad in 2017-18, and nab another high pick: Wendell Carter Jr.

With Arturas Karnisovas displacing #GarPax, most of the focus will be on the futures of LaVine and Jim Boylen — Chicago’s embattled head coach. But the most important question facing Chicago in the near term is something else: Can the Markkanen-Carter front line become what the bullish (sorry) among us thought it could be two seasons ago? If the answer is no, the Bulls are doing nothing interesting over the next few seasons.

The development of Markkanen and Carter is of course linked to LaVine and Boylen. With a few exceptions, every player’s performance is at least somewhat dependent on the broader team ecosystem. Both Chicago bigs need a creative ballhandling partner to loosen the defense — to get them the ball with some small territorial advantage they can build upon.

Chicago’s point guards are not capable of that. LaVine can break down any defense, but he’s a score-first sort with so-so vision and timing as a passer. If Chicago finds better playmakers — through internal development or roster moves — Markkanen and Carter will look better. Same goes if the coaching staff can coax this roster toward a more coherent, flowing offense. Perhaps starting Coby White as de facto point guard — with LaVine, Otto Porter Jr., Markkanen, and Carter — might juice playmaking.

Even setting aside context, both Markkanen and Carter have stagnated over the last year. Markkanen was better as rookie than he has been this season. That’s not great, considering he will already be eligible for an extension this summer. Injuries have played a role. Markkanen looked tentative early this season while dealing with an oblique injury, and then surged in December — before a stress reaction in his right pelvis (ouch!) vaporized another month.

He hasn’t quite found himself on offense. He should thrive as a screen-setter, picking and popping for 3s. If defenses switch to snuff that, Markkanen has flashed the ability to abuse smaller guys in the post. If defenders try to rotate and scramble back to him behind the arc, Markkanen can meander by them with a workmanlike — but effective — pump-and-go game. Trap Chicago’s ball handlers, and Markkanen slips into open space for midrange jumpers — or 4-on-3 attacks.

We haven’t seen enough of that guy. Markkanen looks like a lethal shooter, and projected as one, but he has only hit 35.6% — league average — from deep for his career. Can we really blame it all on Chicago’s lack of ace ball handlers?

And what should Carter be doing while Markkanen performs all that screening goodness? Is he lurking in the dunker spot to catch lobs? Is he spacing the floor? Remember: The Bulls envisioned Carter as an Al Horford-ish hub — a guy who could orchestrate with handoffs and canny passes. Markkanen and Carter actually ran some effective pick-and-rolls together during Carter’s rookie season.

They showed huge potential as an interchangeable screening combination: They toggled between diving to the hoop and spotting up, often as part of staggered screening actions.

Where did that go? The Bulls this season have turned Carter into a bystander. Markkanen’s one-on-one numbers — in both post-ups and isolations — have been bad since he entered the league. The Bulls are averaging 0.84 points per possession whenever Markkanen shoots out of a post-up, or passes to a teammate who launches right away — 74th among 84 guys who have recorded at least 50 post touches, per Second Spectrum.

He has fared much better posting up guards — often the happy result of a switch — but he has done that only 17 times, per Second Spectrum. Dirk Nowitzki, the unfair goalpost for Markkanen, used to do that five or 10 times in a single game.

That number — 17 paltry post touches against smaller guys — is a blaring indicator of minus playmaking and a wheezing offensive system.

I’m still high relative to consensus on both Markkanen and Carter — and on what they can be together. They should complement each other on both ends. They will improve as the team around them improves. Even if Markkanen can’t be The Guy on a top-shelf NBA offense — and he almost certainly can’t — he might still grow into a solid No. 2 as the fulcrum of a pick-and-roll attack.

But the Bulls need to see progress whenever basketball returns. The organization is responsible for helping engineer it. LaVine and White are, too. So are Markkanen and Carter. It’s time.

2. Kyle Lowry‘s iron shoulder

The Heat bestowed the “iron shoulder” moniker on Goran Dragic years ago for this running-back-style move, but Kyle Lowry has also mastered it:

That is for sure a foul, even if Donovan Mitchell exaggerates the impact — and it’s unclear if he does. Lowry is usually cagier concealing his forearm. If you’re 5-foot-11 with limited hops, you need to resort to some chicanery. It’s not really a foul if you get away with it.

It’s an interesting debate: Is the MVP of Toronto’s spirited title defense Lowry or Pascal Siakam? They have played about the same number of games and minutes. Raw numbers favor Siakam. Advanced stats have Lowry by a hair. The on-off numbers point to Siakam; the Raptors blitzed opponents when he was on the floor without Lowry, but barely won the opposite subset of minutes.

But the eye test says it’s still Lowry. You can tell when one player sets the identity for a team, and the Raptors take after Lowry. They play with a certain verve when he is on the floor. They run more. The ball whips around the horn.

They vibrate with energy on defense: on their toes, on a string, rotating and switching and swiping and throwing their bodies into driving lanes. (Lowry is tied for the league lead in charges drawn with Montrezl Harrell.) It looks frenzied, but there is a calm intelligence underlying all that buzzing motion — a deep, almost subconscious confidence that you and your teammates can outthink the opposing offense.

It has been a good year for Lowry believers. He was steady in Toronto’s championship run — pass-first and deferential to Kawhi Leonard when the situation called for it, and capable of bending the game to his will if need be. His closeout performance in Game 6 of the Finals — scoring Toronto’s first 11 points, staking the Raptors to an 11-2 lead — rewrote his legacy forever. Few players have changed the perception of themselves more in one game. It was a We are not losing stand from a player who has rarely shifted into that kind of scoring gear — a player who is not really built (physically) to even have it.

Lowry truthers lived through dark times. He belly-flopped in the 2015 playoffs, though he was battling a back injury and other maladies. Washington humiliated the Raptors in a four-game sweep.

He started slowly the next postseason, shooting horribly against a long-armed Indiana defense designed to torment him. The Raptors survived in seven games, but Lowry opened the next round — an unwatchable seven-game slog over Miami — bricking away again. He finished it with 96 points combined in Games 5-7, including a 35-point masterpiece to ice the series. It was then that Lowry’s postseason story began to change.

He was solid in the next round against Cleveland, though the Raptors could never really trouble LeBron James. Facing the Cavaliers a year later, Lowry was poised and productive — one of the only Raptors who appeared up to the challenge until he turned an ankle in Game 2, ending his season early.

He battled until the end against Cleveland in 2018.

Lowry was never going to be a regular 25- or 30-point scorer in the playoffs. Most guys his size just can’t shoulder that load against elite defenses. Part of being a Lowry truther was believing that even in those single-digit scoring games, he was doing all the little things to help Toronto win. That was often true. But sometimes, you need your best players to do big things, too. You need buckets. You need them to force it when no one else is ready or willing.

Lowry grew to understand that. He has been in full command of the game this season. These Raptors fear no opponent. They wouldn’t be the favorites in the Eastern Conference playoffs, but they can match up with anyone and play any style. No one would be excited about facing them. I hope we get to see an honest championship defense.

3. Devin Booker as Chris Paul

Does this look familiar?

Everything about that — Booker’s patience navigating Deandre Ayton‘s screen, the snaking path to his sweet spot, the smooth leaning release — screams Chris Paul. Paul has suffered a few high-profile postseason meltdowns, but he has also canned a lot of massive shots. He has been the best clutch player in the league this season. He usually ranks toward the top of such leaderboards. His teams almost always outperform expectations in crunch time.

Paul’s right elbow jumper might be the single most effective unassisted, repeatable clutch shot in the league’s post-Jordan history. Dirk Nowitzki’s fading jumper from the post — one leg or two — is right there. Kobe Bryant would certainly like a word. Paul Pierce would interject with his step-back. Kawhi Leonard’s Jordan-esque midrange game is fearsome. LeBron’s robust crunch-time résumé features more stylistic variety. Ditto for Kevin Durant, who is dangerous (ask LeBron’s Cavaliers) once he crosses half court. Golden State fans would nominate Stephen Curry‘s shake-and-bake 3s.

We tend to think of Booker as a long-range marksman, but he is a prolific and quite accurate midrange shooter who can get to this shot whenever he wants. A full 45% of his attempts this season have come from the midrange — a share that ranks in the 97th percentile for his position, per Cleaning The Glass. Only three players — Paul, Leonard, and Russell Westbrook — have attempted more shots from the right elbow, per Second Spectrum.

Booker senses when someone is on his tail, and uses pump-fakes and stop-and-go moves to ditch pursuers:

Booker has shot about 47% on all midrangers over the last two seasons combined — a very strong number, though short of peak Paul and Nowitzki.

Booker takes too many long 2s. There is no way he should average the same number of pull-up 3s as Giannis Antetokounmpo and Jrue Holiday — as is the case this season. But that particular long 2 is a handy crunch-time weapon, and Booker’s proficiency with it opens other parts of his game — including his underrated pick-and-roll passing.

Booker took a leap this season. He was a deserving All-Star. He and the Suns have a lot to sort out, especially on defense, but Booker is really good and should grow into the sort of scorer-distributor who can play a big role on a winning team.

4. No more Bobby Portis post-ups

If you watch the right 15 games every season, you come away thinking Portis is a superstar. He can shoot, and score, and there are nights when it seems like he never misses.

There are many, many other nights when Portis tries to be something more than a spot-up shooter and ends up taking lots of shots like this:

Portis is not posting up to pass or draw fouls; he doesn’t do much of either from the block, per Second Spectrum. He’s not quite physical enough to bulldoze power forwards. When he tries, he often settles for awkward hooks and floaters:

New York has scored only 0.868 points per possession when Portis shoots out of a post-up, or dishes to a teammate who fires right away — 70th among 84 guys who have recorded at least 50 post touches, per Second Spectrum. That is in line with prior seasons.

Portis has played mostly power forward on New York’s gigantic, misshapen roster. His speed and shooting advantages erode there. Portis is dangerous as a fast, stretchy center picking and popping for 3s (which he is always eager to jack). He probably has to play that role as a reserve to mitigate the damage he inflicts on defense, but he’s good enough to be one of those reserves who finishes games when he’s hot.

Just scrap the post-ups.

5. A shooter’s-only cut

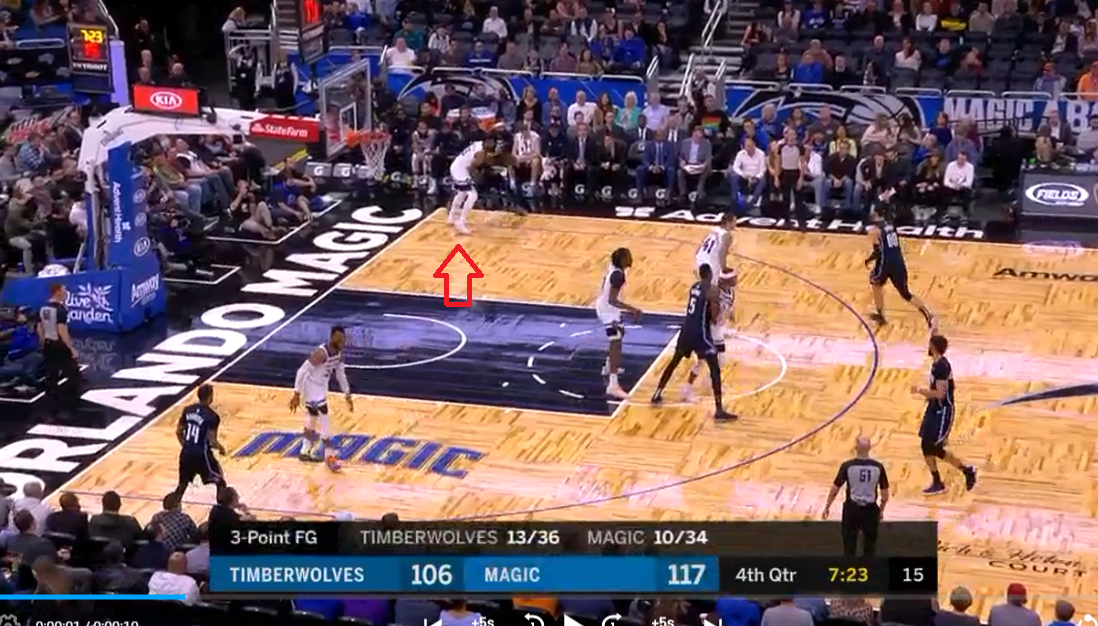

Being a great shooter — or carrying the reputation of one — brings so many downstream benefits. When catch-and-shoot gunners rev up for cuts from the corners, their defenders sometimes play on their backs — almost climbing atop them, as Malik Beasley does here against Terrence Ross:

Aaron Gordon has the ball up top; Ross is primed to sprint to Gordon for a handoff. Beasley knows he has to stay attached to Ross at the hip. Losing ground or cheating under Gordon’s pick risks an open Ross triple.

Every exaggerated tactic designed to take away one thing exposes another:

If the defender is on your back, conceding a head start, why not abort the handoff and slice to the rim?

The only plausible help defender here is Naz Reid, guarding Mo Bamba at the left elbow — on the weak side. Gordon’s man can’t crash down on Ross because Gordon has the ball. No one else is really in help position.

Reid is too slow reading the play, even though there is nothing going on in his area to distract him.

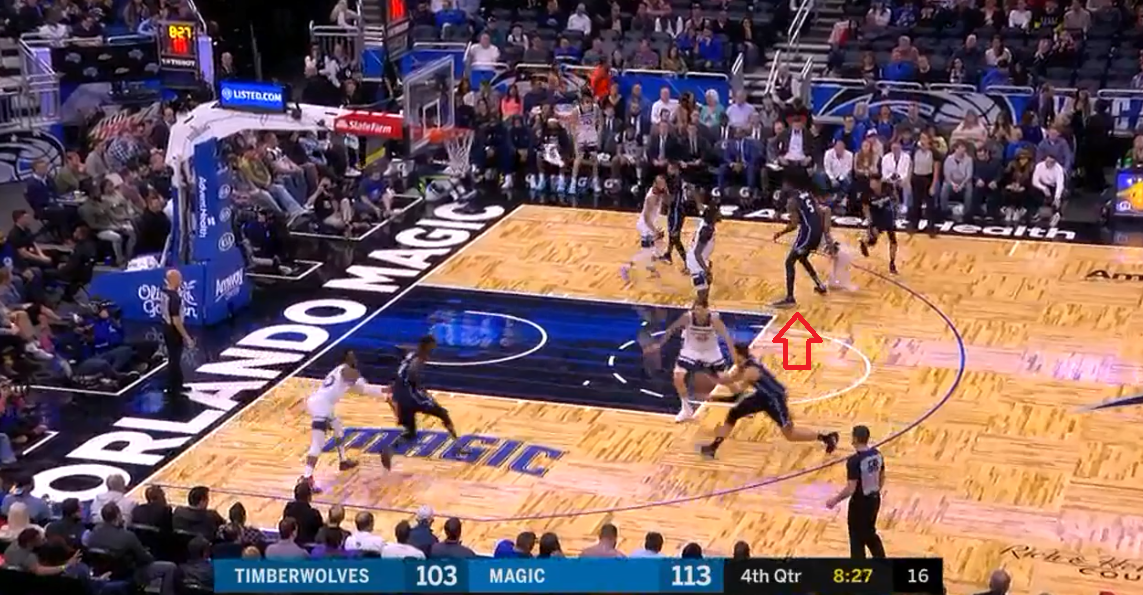

The Magic plant a token distraction on this one:

Josh Okogie starts the play in that chase-from-behind stance, and Ross again goes off-script for a rim-run. Reid doesn’t register any of this; he’s fixated on Bamba setting soft off-ball picks — dummy action:

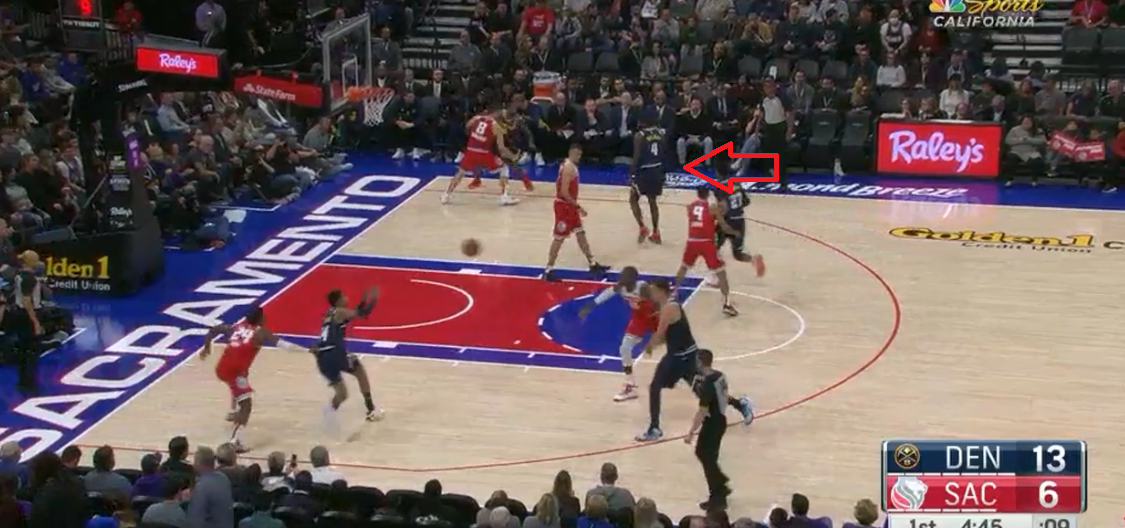

Gary Harris might be the current master of this specific cut. It helps playing with Nikola Jokic, a passing wizard who signals cutters with winks and head nods:

Nemanja Bjelica is the designated helper there, and he’s late — in part because Denver has his man, Paul Millsap, set diversion screens:

The inverse of the climb-on-back ploy is to play between the corner shooter and his screener — to try to pin the shooter along the baseline and prevent him from using the pick at all. (This is called “top-locking.”) The obvious antidote is a backdoor cut.

Basketball is cool. I miss basketball.