“I can remember going along a fast straight and overtaking a twin-engined aircraft that was flat-out at 140 mph. I was doing roughly 190 mph. That made me think, ‘Crikey, this really is a quick car.'”

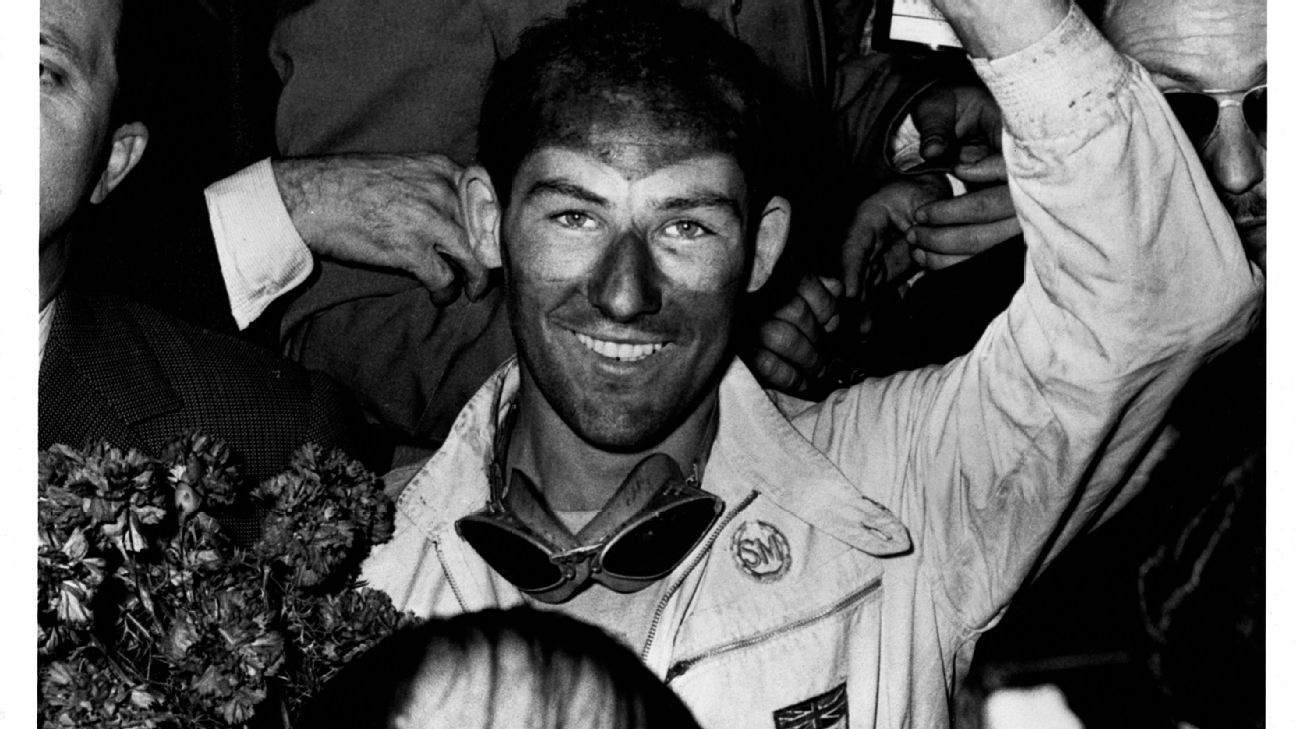

It was a moment that Sir Stirling Moss, who died at the age of 90 on Sunday, would never forget. In 2012, 57 years after his famous round trip from Brescia to Rome and back again, Moss still got excited about the 1955 Mille Miglia as we sat down for an interview in his office on the ground floor of his Mayfair home. Surrounded by memorabilia from his remarkable career, he regarded that race as the finest of his 197 professional victories. And just looking at the bare statistics, it’s easy to understand why.

Driving a 310bhp Mercedes 300SLR — essentially an F1 car with headlights — he averaged 97.96 mph over 992 miles of closed public roads, setting a record time of 10 hours, 7 minutes, 48 seconds. He only escaped the tight confines of the cockpit once, to relieve himself in Rome, and spent the rest of the trip mounted over the Mercedes’ propshaft, which passed between the driver’s legs and separated the 300SLR’s clutch and brake pedals by the best part of 24 inches.

Amid coughs of dust from the in-board brakes, waves of sickening heat from the transmission and spits of petrol from the fuel filler cap behind his head, Moss reached speeds that would have registered a new land-speed record 30 years earlier.

But while Moss’ performance was sublime, it was only possible with the help of his co-driver, and Motor Sport magazine journalist Denis Jenkinson. Jenkinson rode in the passenger seat throughout, giving Moss vital information on the road ahead with a series of hand signals while making mental notes for his must-read write-up in the next issue of Motor Sport.

His “secret weapon” was an 18-foot-long roll of pace notes — “the toilet roll” — that was coiled within a specially designed alloy box with a Perspex viewing window. At the time, such a system was quite ingenious and it was the only way the pair could hope to compete with the local knowledge of the Italian drivers, who had won the event every year since the war.

In the months leading up to the race, Moss and Jenkinson compiled their pace notes with a series of practice runs in various Mercedes machinery. On these reconnaissance laps the pair would fastidiously analyse each corner, grading them as “saucy ones, dodgy ones and very dangerous ones” depending on road surface and severity. But as Moss got as close to racing speeds as possible while avoiding the local traffic, the practice laps were not without danger and, rather inevitably, two cars were written off.

One, a development 300SLR, met its end after coming across a loose sheep at 70 mph. Another, a 300SL “Gullwing,” collided with an Italian military truck at one of the route’s many junctions. But for Mercedes it was merely collateral damage in the pursuit of victory, and team boss Alfred Neubauer’s main concern was for Moss and Jenkinson.

After each practice run in the 300SLR, Mercedes mechanics assessed its wear and tear in an effort to minimise the chances of a problem on race day. One of the test cars completed the equivalent of six Mille Miglias, with all four of the Mercedes team drivers — Moss, Juan-Manuel Fangio, Karl Kling and Hans Herrmann — pushing it to its limits over the pot-holed mountain roads. Moss never drove another car quite like it

“The greatest car built, in my mind, was the 300SLR Mercedes,” he told ESPN in 2012. “There’s a car that was unbreakable, really. I did the Mille Miglia with it and the last 340km — that’s having driven for 800 miles or so — I managed to average 165.1 mph, which just shows you that that car was just the same at the end as it was at the beginning.

“It was just fantastic, I never ever got into a Mercedes thinking, ‘I hope the wheel doesn’t come off’ or ‘I hope this or that doesn’t happen.’ All the other cars — mostly Lotuses — it was a concern, particularly if you are going between trees and things.”

Such confidence in the machinery meant the Moss/Jenkinson 300SLR (race No. 722, chassis No. 0004) took a bit of a battering over its 1,000 miles. Ahead of the race, Mercedes ordered Moss to set the early pace in order to push the reliability of its Italian rivals to the limit. One of the cars the team was hoping to stretch to the breaking point was the 4.4-litre Ferrari of Eugenio Castellotti, which started a minute behind Moss but was right on his tail as they arrived in Padova 100 miles later. Heading onto the town’s main street, Moss locked a brake and ran wide, collecting a straw bale in the process and presenting an opportunity for Castellotti to get past. Once ahead, the Italian used his Ferrari’s extra 20bhp to pull away, but as Jenkinson noted in his report, it was at the cost of his tyres.

“Through Padova we followed the 4.4-litre Ferrari and on acceleration we could not hold it, but the Italian was driving like a maniac, sliding all the corners, using the pavements and the loose edges of the road. Round a particularly dodgy left-hand bend on the outskirts of the town, I warned Moss and then watched Castellotti sorting out his Ferrari, the front wheels on full understeer, with the inside one off the ground, and rubber pouring off the rear tyres, leaving great wide marks on the road.”

The Ferrari reached the Ravenna check-point two minutes ahead of Moss and Jenkinson, but its tyres desperately needed changing and the Mercedes retook the position. On the following stretch the Ferrari’s six-cylinder engine couldn’t match Castellotti’s enthusiasm and the Italian was forced to retire. Job done for Moss and Mercedes.

The 300SLR continued at full pace until the next checkpoint, literally flying over bumps on the straights (Jenkinson estimated one jump to be 200 feet in length) and sliding sideways through tighter sections. When they reached the Pescara checkpoint they were 15 seconds off another one of Moss’ earmarked rivals, Piero Taruffi’s 3.7-litre Ferrari. On learning the news, Moss pushed even harder and on one corner ran straight through a bunch of straw bales lining the exit. Fortunately for him, there was nothing more solid in the run-off area and the car emerged safely on the following straight with another sizable dent in the Mercedes’ now characterful front end.

Despite the battering, the only serious problem Jenkinson noted with the 300SLR was a grabbing brake, which nearly spelt disaster on the Radicofani Pass. Jenkinson’s Motor Sport column takes up the story: “Without any warning the car spun and there was just time to think what a desolated part of Italy in which to crash, when I realised that we had almost stopped in our own length and were sliding gently into the ditch to land with a crunch that dented the tail. ‘This is all right,’ I thought, ‘we can probably push it out of this one,’ and I was just about to start getting out when Moss selected bottom gear and we drove out — lucky indeed!”

Other than that one “moment,” Moss remembers the car as a dream to drive: “Coming to things like the Futa [Pass], the balance of the car, the way one could break away the rear end and put the power down, it was just a very rewarding car. The thrill of going 1,000 miles like that is very difficult to describe.”

Fortunately, Jenkinson was on hand to observe Moss and give an account of his driving.

“We certainly were not wasting any seconds anywhere and Moss was driving absolutely magnificently, right on the limit of adhesion all the time, and more often than not over the limit, driving in that awe-inspiring narrow margin that you enter just before you have a crash if you have not the Moss skill, or those few yards of momentary terror you have on ice just before you go in the ditch,” he wrote. “This masterly handling was no fluke, he was doing it deliberately, his extra special senses and reflexes allowing him to go that much closer to the absolute limit than the average racing driver and way beyond the possibilities of normal mortals like you or me.”

Moss’ blistering pace, combined with the blisteringly hot weather, meant the Mercedes was storming through the checkpoints at record pace. By the halfway point at Rome, he was two minutes clear of Taruffi, and by the time they reached Florence, the Ferrari had dropped out with an oil pump failure. By that time, Mercedes dominated the top three, with Herrmann in second and Fangio, suffering from a fuel injection problem, in third. A punctured fuel tank accounted for Herrmann’s Mercedes as he traversed the Futa Pass, and that left Moss with a 30-minute advantage over Fangio.

By the time he returned to Brescia and crossed the finish line, he was 32 minutes clear of Fangio, with Umberto Maglioli’s Ferrari a further three minutes off the pace in third. Not only had Moss dominated the opposition, he had shattered all of the event’s previous records. The combination of his driving talent, Jenkinson’s hand signals and the unrelenting speed and reliability of the Mercedes 300SLR was simply unbeatable.

“We’ve rather made a mess of the record, haven’t we — sort of spoiled it for anyone else,” Moss said to Jenkinson after the race. “For there probably won’t be another completely dry Mille Miglia for 20 years.”

In fact, there were just another two Mille Miglias before the Italian authorities banned the race in 1957 following two fatal crashes, one of which killed nine spectators. Moss’ record was never matched or bettered and became all the more celebrated because of it. It is now the stuff of motoring legend, but fortunately it can be relived again and again through Jenkinson’s Motor Sport account. It’s an absolute must-read for any motorsport fan.