TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — A 19-year-old former high school basketball player tries to walk on at the local community college when he learns his daughter will be born with spina bifida. She’ll need multiple surgeries, just for starters. He drops out of school and gets a job at Red Lobster. Then IHOP. Then he walks into a local boxing gym, a facility that is not easy to find in west-central Alabama.

He has no expectation of fame or fortune — just quick cash as an opponent. He also has a 4 a.m. route delivering kegs for a local beer distributor. Doesn’t matter. Still not enough money. It’s not working out with his daughter’s mother, either. He is heartbroken. He is ashamed of himself.

At one point, with a .40-caliber pistol on his lap, he considers suicide: “If I pick this gun up and blow my brains out, everything will be OK. All my problems would go away.”

That’s the devil talking. On his other shoulder, a profane angel: “‘Man, you gonna go out like a b—-? You can’t do that. You got a little girl that needs you more than anything.”

The angel wins.

He goes back to the gym, outside of which he often is seen in his truck, sleeping between his beer run and his workout.

The now-former basketball player and his trainer — self-taught trainer, actually, as the guy gave up a promising career as a television reporter to learn the boxing game — are habitually short on gas money. A particularly arduous sparring session in Atlanta leaves them with just enough for a post-workout meal. Cheetos and Mountain Dew for the coach. Gummy rings and lemonade for the fighter.

But along the way, the fighter finds something. It wasn’t just a right hand — more like a superpower.

Less than three years after he walked into the gym, at 22, he medals at the Beijing Olympics.

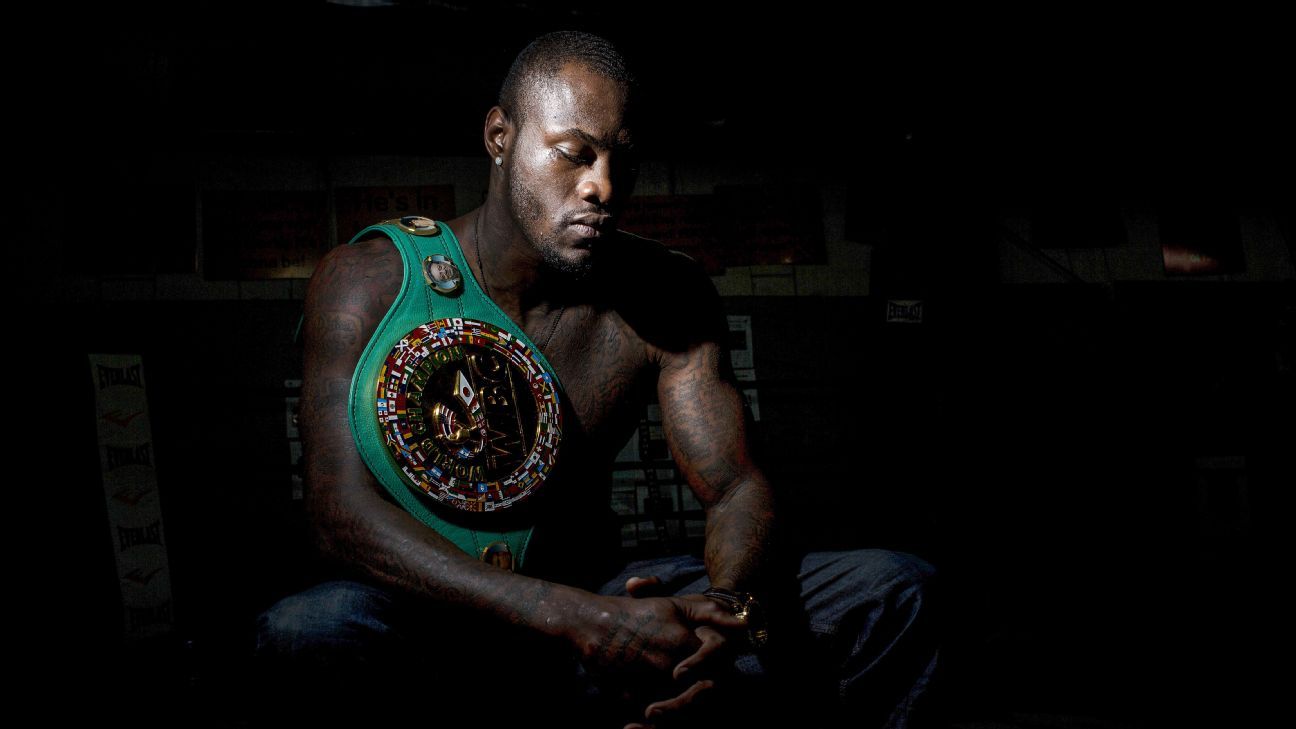

At 29, he wins the WBC heavyweight title.

Still, no one pays much attention.

If boxing people tend to diminish his skills, the general public remains steadfast in its obliviousness.

Meanwhile, he sees to it that his daughter has everything she ever needs.

Today, she is on the cheerleading squad.

He has seven other kids too.

And he keeps knocking people out — in a manner never quite seen before. His right hand is likely the single-most destructive weapon in the history of boxing.

Still, America didn’t really care about Deontay Wilder until he fought Tyson Fury.

And now that they’re about to fight again, the time has come.

Attention must be paid.

IN DECEMBER 2014, the month before Wilder won the title he still holds, I did a piece for Showtime. At the conclusion of the interview, Wilder’s daughter Naieya approached with cheerful insistence and asked, “Do you want to see me do a cartwheel?”

She was smaller than you’d expect a 9-year-old to be and walked with a pronounced hitch in her gait. We all looked at each other, the guys on the crew, pretty much thinking the same thing. But before any of us get out a “don’t hurt yourself,” she had climbed up into the ring, executed a near-perfect cartwheel and nailed the landing.

In 34 years as a newspaperman and broadcaster, it remains the most sublime victory I’ve ever witnessed — not merely a surprise, but an altogether pure one. Naieya’s father had more than a right hand; he had an even more precious commodity, a story. Deontay Wilder was worth cheering for.

In January 2016, we did another piece, walking down Times Square. Wilder had held the title for a year by then, but no one really knew who he was — although I do recall a tourist asking if he was LeBron James.

Americans said they wanted a heavyweight champ. They wanted a knockout artist. But when he finally arrived on the scene, he was barely acknowledged.

Why? I asked Wilder, when we met a few weeks ago.

“Race plays a huge part in it, you know?” he said.

Wilder wasn’t venting about racism. It’s not something he dwells on. Still, at some level, his point seems unassailable. If Wilder were white, it would be easy to imagine him as the face of IHOP or the beer he used to distribute.

That said, race didn’t keep Mike Tyson or Evander Holyfield or George Foreman from entering the American consciousness. Unlike his predecessors, though, the promotion of Wilder always seemed to lack a sense of risk or imagination. You don’t get over without a signature win. I get it: Gimmes, mandatories and stay-busy fights are part of the business. But Wilder lacked what his elite contemporaries — Fury and Anthony Joshua — received in beating Wladimir Klitschko.

The Fury fight changed all that.

It wasn’t supposed to be that much of a fight. Fury was still feeling his way back from a suicidal depression and had just lost more than 100 pounds. If the historic draw frustrated the fighters, though, it also gave them what they needed. Epic fighters need epic antagonists.

Still, what held back Wilder more than anything — more than race, lackluster promotion or the years spent waiting for a worthy opponent — was the rise of a pervasive, if unmentioned, prejudice against the American heavyweight. In the not so distant past, of course, the notion of an American heavyweight champ was a redundancy. I mean, with rare exceptions, of course he was American.

So what happened?

He’s catching passes, sacking quarterbacks or trying to break backboards. Say you’re 6-foot-5 and 240 pounds with a decent 40-yard dash time or a good vertical. Do you want to live in a cushy athletic dorm and receive treatment in state-of-the-art facilities? Or would you prefer to apprentice in a room lit by the dim flicker of fluorescent bulbs, suffused with male stank, where it is all but certain that no one ever bothers to clean the spit buckets?

The typical American heavyweight has become a guy who already has failed, for whatever reason, as a ballplayer. Boxing was not his first sport. He has been recycled, and the public has long since caught on.

It takes more athletic prowess to be a fighter. Wilt Chamberlain might’ve loved talking about Muhammad Ali, but at least he had the good sense to stick to volleyball. Not so for Ed “Too Tall” Jones, Mark Gastineau, Kendall Gill. I can only assume it will be the same for former wide receiver Brandon Marshall.

Even the best of these recycled athletes — real talents who dedicated themselves for years — couldn’t become champions. Michael Grant was a three-sport star back in Chicago, but Lennox Lewis took him out in two rounds. Dominic Breazeale, a 6-foot-7 former college quarterback, had two championship bouts. Breazeale lasted into the seventh against Joshua, but only 137 seconds against Wilder.

And that’s the point: Wilder is different.

While generations of mere ballplayers have tried, he is the only one to become a champion.

Still, the presumption against American heavyweights persisted — even in Wilder’s own hometown.

“People who used to be haters, now they’re fans. That’s cool,” said Chris Bates, Wilder’s bodyguard and camp consigliere. “But there was a high percentage of people who would [say], ‘Ah, he hasn’t fought anybody.’ … And I’m like, ‘How many people you know been to the Olympics?’… This is Tuscaloosa. All they know is Alabama football. … If he were from another country, he would be huge. But he’s from here, so they’re like, ‘He can’t be boxing.'”

For years, the conversation in boxing circles focused not on what Wilder had already done — such as winning an Olympic medal in less than three years after first walking into a gym — but on what he hadn’t yet mastered. Yes, his feet aren’t great. And yes, he gets wild. But even when flailing away, he could take you out. Recalling the Malik Scott fight in 2014, a first-round knockout from, of all things, a slapping left hook. The conversation that followed had less to do with Wilder than the baseless notion that Scott had taken a dive.

3:38

Deontay Wilder does not regret saying he wants a body on his record and adds that fans are paying to watch him knock people out.

WHILE IT TOOK years for people to comprehend his actual power, it was there from the start, hiding in plain sight.

Three weeks after Wilder walked in off the street, he caught a journeyman pro with a right hand. The guy went down, first round. Another man would’ve been ashamed. But the journeyman had been around long enough to know exactly what hit him.

From his perch on the ring apron, Jay Deas — who to this day remains Wilder’s trainer — saw the journeyman laugh as he struggled to his feet. “Whatever you do,” he told Deas, “keep this guy.”

Back in the day, Deas would spar with all the beginners himself. For Wilder, he wore headgear with a metal cage. Wilder broke the cage with a single right. Even an extra-thick body suit affords little protection, as Deas has suffered countless broken ribs and even a hernia from the body shots. After a mitt session, his elbows often swell up the size of grapefruits. Wilder’s longtime assistant trainer — Olympic gold medalist and former welterweight champion Mark Breland — considers himself lucky that the worst thing Wilder left him with was a separated shoulder. Today, Wilder uses three mitt men for every workout.

At 6-foot-7 and maybe 220 pounds, Wilder, 34, is longer and lighter than most heavyweights. What’s more, his right defies one of boxing’s most ancient conventions. From Jack Dempsey’s “shovel hook” to Tyson’s right uppercut, from Rocky Marciano’s “Susie Q” to the clubbing right with which Foreman knocked out Michael Moorer, the most devastating blows were always thought to be the shortest, the most compact, the most brutally efficient. But Wilder’s right hand unfurls like a whip, often camouflaged by a blinding jab.

While the power is natural, what’s left in its wake is profoundly disturbing. Survey the images on YouTube, if you must: Breazeale; Luis Ortiz; Bermane Stiverne; Siarhei Liakhovich, a former heavyweight champ, his legs flailing about on the canvas like a fish on a dock; or the motionless body of Artur Szpilka.

“I thought I killed him,” Wilder said, recalling Szpilka — motionless, waiting for his chest to heave, to draw breath again.

It isn’t an uncomfortable memory for Wilder, at least it doesn’t seem that way. Truth is, even after all these years, the champion remains in awe of his own power. But like most unexplainable phenomena, the gift comes with a corresponding curse, not merely hubris, but a majesty corrupted with a whiff of something ugly.

“I want a body on my record,” Wilder has said. He has said it a few times, actually.

Every knockout is a metaphor for death, but he wasn’t speaking metaphorically. And it’s a shame to think what began as a life-affirming quest — to pay Naieya’s medical bills — ever came to this.

I ask if he has any regrets.

“I don’t regret nothing I say,” he says. “I mean what I say.”

Last July, after a fighter named Maxim Dadashev died from wounds suffered in the ring, Wilder tweeted his authentically heartfelt condolences. He proclaimed Dadashev a champion, even though he hadn’t won a belt. But how did Wilder reconcile his compassionate self, the guy who bestowed such honor on the fallen, with the guy who wanted a body?

Was this gamesmanship gone too far? Vanity or fear? And where was the profane angel now?

For the record, Wilder makes the distinction between his personas. There’s Deontay from Tuscaloosa, and there’s the bloodthirsty alter ego with which he steps into the ring. The guy who wants a body, he says, “That’s the Bronze Bomber.”

“Anybody can take it how they want,” Wilder says. “Because at the end of the day, you’re going to pay your money and you’re going to come to try to see someone get knocked out. That’s the whole anticipation of coming to a heavyweight fight.”

“Especially this one,” I concede.

He snorts a laugh. His own form of concession: “We risk our lives for others’ entertainment. Because at the end of the day, somebody want to see somebody’s brains get knocked out of their head. And how nasty that may seem or how cruel … you’re getting up to see it. So you’re just as guilty as the ones saying it.

“For 12 years, I’ve been mesmerizing people off the knockout. If I go out there and just tap, tap, tap, I’d get booed out of the arena.”

The people know.

“They know the guy who knocks people out, the one-hit man, the guy with devastating power, that God-given power. The suspense: What’s gonna happen when the Bronze Bomber hits him?

“That’s what everybody is waiting for.”

And now more than ever.

It’s worth mentioning that Fury, 31, has gone dark too.

“Cut the ears off and the nose,” Fury said, “it wouldn’t stop me from fighting. Take an eye out, I still fight on. I’m a fight-to-the-death man.

“I’d have been well-suited for gladiator days.”

Wilder can identify with that.

“I like Tyson Fury, as a person,” Wilder said. “So many guys, they’re scared to talk.”

I’m glad they have each other. Even if one of them has to go.