GOLDEN STATE WARRIORS president Rick Welts was in his old office up in Oakland when the call came in. Warriors general manager Bob Myers was checking in, as he often did, after the team’s shootaround in Los Angeles.

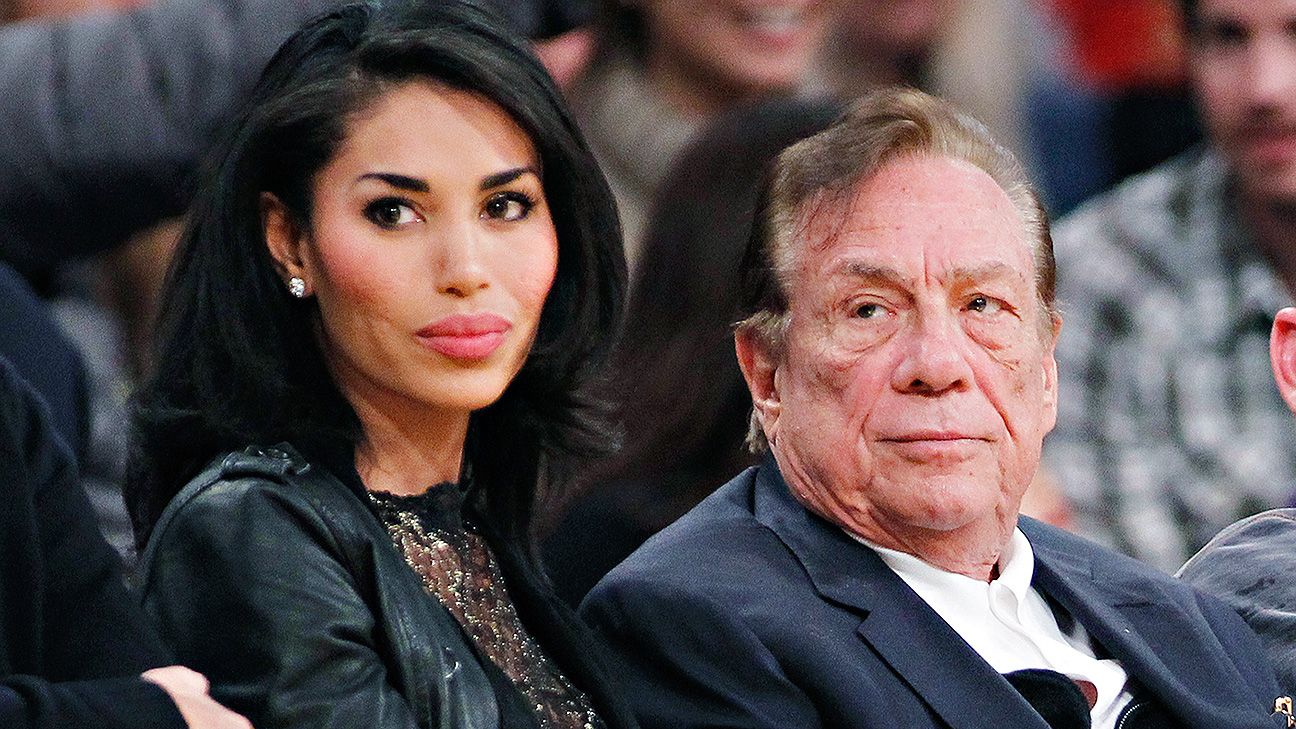

It was the morning of Game 5 of the Warriors‘ 2014 first-round playoff series against the Los Angeles Clippers. Four days earlier, TMZ had published voice recordings of then-Clippers owner Donald Sterling making racist statements to his mistress, V. Stiviano, throwing the NBA into a tailspin.

When Myers called his boss with a status report, he told him in no uncertain terms, “‘These guys are going to walk off the floor,'” Welts recalled.

“He was with the team that morning and said the vibe around the team — maybe both teams — was that if this doesn’t go the way the players want it to go that they could walk out on the floor and then walk right off and not play the game that night,” Welts said.

Donald Sterling had been a blight on the NBA for three decades. There were dozens of incidents that could have been grounds to kick him out of the league, but this tape was something else.

“In your lousy f—ing Instagram, you don’t have to have yourself walking with black people,” Sterling told Stiviano. “It bothers me a lot that you want to promote, broadcast that you’re associating with black people. Do you have to?”

At one point, Stiviano asks Sterling, “Do you know that you have a whole team that’s black, that plays for you?”

He responds: “Do I know? I support them, and give them food and clothes and cars and houses. Who gives it to them? Does someone else give it to them? Who makes the game? Do I make the game, or do they make the game?”

The NBA’s players were appalled. They threatened to boycott playoff games if new NBA commissioner Adam Silver didn’t get rid of Sterling quickly and definitively.

“There’s no room for that in our game,” LeBron James, then of the Miami Heat, said the morning after the tapes were released. “Can’t have that from a player, we can’t ever from an owner, we can’t have it from a fan, and so on and so on. It doesn’t matter if you’re black, white, Hispanic or whatever the case may be. We can’t have that as part of our game.”

Silver was less than 90 days into the job, and he had a full-fledged crisis on his hands. The players were on the verge of shutting down the league in protest. And the threat was far more credible than anyone knew at the time.

“I was all-in. Like shut down the whole season,” then-Warriors forward Andre Iguodala said. “Maybe that was too far, but as far as that game that day, you can reschedule it, you gotta sort this thing out, because there’s some deep-rooted stuff with him that had to be addressed.”

The Clippers. The Warriors. The NBA. It was uncharted territory for everyone. No team had ever refused to start a game in the NBA before, never mind the playoffs. It would have been an incredible statement.

“If we didn’t play,” then-Clippers guard Jamal Crawford said, “I think that honestly it would have outlived us. They would be talking about that while we’re not here anymore.

“It’s never happened. At that magnitude, at that level.”

And if the Clippers and Warriors boycotted one game, what would happen to the rest of the playoffs?

“If we didn’t play the first game,” Crawford said, “I don’t think we would’ve played any games, to be honest with you. I think that just would’ve been that, until something happened.”

Five years later, that what-if remains one of the great unanswered questions in league history. Because something did happen to turn that train around. And instead of shutting down the league, the moment turned the NBA into what it is today.

THERE ARE MANY REASONS why this tape caused Sterling’s downfall. The world he had once ruled, all the people he had once had power over — his players, his mistress, his wife, the NBA — finally had a way of fighting back.

Stiviano wasn’t the first woman who wanted revenge after a relationship with Sterling had gone awry. But she was the first who had the technology and platform to blackmail him.

“I think the organization knew, and I’m sure the NBA knew, like we have a bad apple,” then-Clippers forward Matt Barnes said. “And he finally f—ed up. And we have proof now. I mean we have tape now.”

The tapes were recorded on Stiviano’s cell phone. The story was broken on a celebrity website, TMZ, which hadn’t existed a decade earlier, by a reporter who had no background covering the NBA.

“The first thing I did was say, ‘Who’s Donald Sterling?'” said Mike Walters, the reporter who broke the story for TMZ and who now runs his own website, The Blast. “I had heard the name, I knew that Donald Sterling was important, but I had no idea that he owned the Clippers.”

Would a mainstream media outlet have run the story in the same way TMZ did?

“I wasn’t a sports reporter — so I think right there changes the mentality of somebody who’s going to run a story like this, period. Because there’s politics in news gathering,” Walters said. “There is a balance between privacy of people and the public’s interest. And I think everyone will agree with me when I say this — this had to be heard, period.”

Once it was heard, it couldn’t be unheard. A reckoning was coming. Within 48 hours, President Barack Obama was answering questions about Sterling.

“I suspect that the NBA is going to be deeply concerned in resolving this,” Obama said. “The United States continues to wrestle with a legacy of race and slavery and segregation that’s still there.”

Within four days, the entire course of NBA history had changed. The tapes went viral and dominated the news cycle. Everything happened at warp speed. Giant decisions, such as whether to boycott playoff games, had to be made at the same time the players were still processing what Sterling had actually said on the tapes.

“We all have family, friends, people that we hadn’t talked to in a while that were like, ‘You guys cannot play!'” Crawford said. “I remember Q-Tip from A Tribe Called Quest hit me and was like, ‘You guys cannot play. This is bigger than you. It’s so much bigger than you. You guys can really send a message.’

“I was like, ‘Man, I hear where you’re coming from.’ But at that time, I didn’t know what we were going to do.”

The Clippers players were genuinely torn. As much as they hated what Sterling had said, they hated the idea of him derailing their season even more.

“We were trying to decide what to do, and everybody was saying we should boycott, we shouldn’t play,” then-Clippers forward Blake Griffin said. “The idea was like, OK, we haven’t been playing for him in the first place. We didn’t gather up before jump ball and say, ‘Donald Sterling on three! One, two, three!'”

Instead of boycotting Game 4, the Clippers players took off their warm-up jerseys, turned them inside out to cover up the team logo and threw them down in a pile at midcourt.

If the Clippers and Warriors didn’t play as a form of protest, no one is quite sure of what would have happened next.

“You gotta do some game theory there,” Welts said. “Would other teams have decided not to play? Would our teams decide not to play the rest of that series? I don’t know.”

Welts had worked in the NBA for decades, and he had never seen anything like this.

“I flew down and couldn’t get very close to Staples Center because of the police barricades and cops in riot gear on horseback,” he said.

Myers had talked to his players and thought about their position.

“I mean, if that is the decision our players had made,” Myers said, “who am I to tell them not to do that?”

IT WASN’T IMMEDIATELY clear what Silver could do to make it right, but his instincts told him that he must work closely with the players to find the right answers.

They would be partners in this, not on opposite sides of the collective bargaining table. But to work with the players, Silver needed them to trust him. So he asked them for a bit of time — days, not weeks — for due process to take its course.

In his gut, he believed Sterling had to be expelled from the NBA forever.

“I believed that he had crossed a line that broke the essence of the contract of the moral fiber of this league,” Silver said. “And I didn’t think it could be repaired.”

But how exactly do you remove an owner — in four days? The NBA bylaws gave Silver authority to act unilaterally in the “best interests of the game.” But there’s no “banned for life” clause in the NBA constitution.

“Should we kick him out? Go outside of the constitution?” Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban said at the time. “Should we start taking steps to really condemn people for what they say in the privacy of their own home? It just happens to be recorded. That’s a slippery slope I don’t want to get on.”

Most believed Silver’s powers were limited to suspending Sterling and fining him $1 million. And even that kind of punishment was fraught with risk. As everyone expected the famously litigious Sterling to sue the league, as he had previously, when he moved the Clippers from San Diego to L.A. without authorization.

“There is a balance between privacy of people and the public’s interest. And I think everyone will agree with me when I say this — this had to be heard, period.”

Former TMZ reporter Mike Walters

No, the only people who could revoke Sterling’s ownership were the other owners, and it would take three-quarters of the NBA’s 29 other owners to vote to kick out one of their own. And some of those owners had a problem with setting a precedent of taking away people’s franchises because they were caught on tapes they never thought would become public?

Silver decided to do it anyway. He wrote his speech on a flight from Portland to New York and then later that night at his home.

“I will say that there was probably an advantage in my newness to the job in that it all happened so quickly,” Silver said. “I didn’t spend a lot of time putting my actions into a broader context of sports leagues or society because I had an immediate issue that required an immediate decision.”

ON THE MONDAY before Game 5, the city of Los Angeles was anxious. Civil rights leaders such as the Rev. Jesse Jackson had flown in. NBA players such as Steve Nash and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar were planning to march on City Hall. Extra police were dispatched downtown.

The phones at the Clippers’ offices had been ringing off the hook with calls from angry, hurt people: You’re scum for supporting a racist like Donald Sterling. You’re just as racist as he is. There were death threats. The whole situation was so traumatic that the NBA had to call in a crisis counselor.

Longtime Clippers broadcaster Ralph Lawler wishes he would’ve seen one.

“I remember my broadcast buddy Brian Sieman saying, ‘You’ve got to go sit down with that person and talk to him. You’re all messed up,'” Lawler said. “I did not do that. I perhaps should have; I might have shortened my period of shock and grief.

“It was such a terrible time for all of us. I may have handled it as poorly as anybody, because I’d been around for so long, 35 years in or something or other, and it just really rocked me.”

Clippers coach Doc Rivers heard about what the team’s employees had been experiencing and felt compelled to meet with them to try to help.

“The employees were threatening to walk out,” Rivers said. “They were getting bombarded by people calling them Uncle Tom, racists — and they didn’t do it. Donald did it.

“Adam had texted me several times, ‘Hey, you’re doing great. Just keep doing it. I don’t want to give you any guidance. Whatever you’re doing is perfect. Just keep doing it. But here’s my number.’

“I’m thinking, ‘OK, great. I’m not going to call Adam Silver.’ But when I went to that meeting and saw those employees with no one leading them — that was the day I called Adam and said, ‘Help.'”

Silver couldn’t tell Rivers exactly what he was planning to say at his news conference the following day, on that Tuesday morning of Game 5, but he tried to reassure him that justice would be served.

“He said, ‘Doc, by tomorrow, you will never have to deal with him again,'” Rivers recalled. “I need you for 24 more hours.'”

SILVER HELD A NEWS CONFERENCE in the late morning to announce that Sterling had been banned from the NBA for life. The city erupted with joy. Cars driving by the Clippers’ practice facility honked and the drivers waved flags out the window.

Instead of a shutdown, Game 5 turned into a celebration. The protests at City Hall were canceled. The stands were filled with fans wearing black. All the ads had been covered in black, as sponsors had begun to disassociate with anything connected to Sterling.

At game time, each NBA team turned its website to black, with a message: We Are One.

“I felt the energy,” Rivers said. “It was the liveliest building I had ever been in as a Clipper. It was amazing.”

It was a watershed moment in the league. The players had protested, and the league not only listened, but took their side against an owner.

“The only people that were going to really make a change were Adam Silver and the other owners,” Griffin said. “They, to their credit, they did do that.”

It validated the players’ growing power in the league and signaled that Silver’s leadership style would be far different than his predecessor, David Stern. Silver’s NBA would be a partnership, in both growing the business and corporate governance.

“It’s a fight that didn’t begin with Donald Sterling,” said Michele Roberts, who took over as director of the National Basketball Players Association later that year. “It’s been happening historically, both in our game and other sports, for many, many, many years.

“The players I work for are men, and men don’t tolerate the kind of ignorance that was Donald Sterling. You don’t tolerate that in your space.”

Five years later, during the 2019 NBA Finals, a minority investor in the Warriors was barred from the NBA for a year for putting his hands on Kyle Lowry as the Toronto Raptors player chased a loose ball into the stands.

The willingness of Lowry, Stephen Curry, Draymond Green and LeBron James to publicly condemn the minority owners’ actions shows just how much the league has changed because of the Sterling scandal. Players had never stood so strongly against those who have power over them. Now it happens all the time, across all sports.

Accusations of sexual misconduct have toppled industry titans. A racist tweet can end a career. Even the term owner has gone out of fashion. Adam Silver prefers the term “governor.” Steve Ballmer paid $2 billion to buy the Clippers from the Sterlings but calls himself their chairman, not owner.

And this summer, in a delicious irony, Kawhi Leonard and Paul George flexed their power, essentially forcing their way from the franchises to join Ballmer’s new-look Clippers.

This idea of player empowerment has received a lot of attention in the NBA over the past few years. Star players asking, sometimes demanding, to be traded with years left on their contracts can be incredibly destabilizing to a franchise. Owners do not like when players have that amount of power over their franchises. And so now they look to Silver to restore the power they once had over players.

“There’s enormous respect, I find, by players for management and owners,” Silver said. “And I think it’s an ecosystem where everyone has leverage, everyone has rights, but it doesn’t mean that it doesn’t require an ongoing calibration of those rights.”

RIVERS DOESN’T LIKE to spend much time reflecting on Donald Sterling and why it took 30 years of misbehavior to finally get him out of the league. Nobody with the Clippers likes to reflect much on their previous owner. They’ve moved on. If they could, they’d forget about him and his era forever.

But Rivers remembers exactly how it went down. They all do, even if they don’t like to relive it.

About 10 days before TMZ released the tapes, then-Clippers team president Andy Roeser had told Rivers that an unflattering tape of Sterling might come out. Initially, Rivers didn’t think it would be a big deal.

“Honestly, I thought it was a sex tape, because of Donald Sterling,” Rivers said. “But then I had forgotten about it, because nothing happened.”

The eccentric billionaire had certainly gotten himself into and out of unsavory situations in the past — federal housing discrimination lawsuits, civil cases with women that produced lewd testimony that eventually went public, even a lawsuit in which Basketball Hall of Famer Elgin Baylor accused him of having a “plantation mentality.”

“When you talk about a plantation mentality, you’re talking about someone who believes that my only value is what I can do for you,” Roberts said. “And not because I want to [do something for you], but because I have to. It obviously harkens back to slavery, which is the most painful period for an African-American in this country.

“That’s exactly what Sterling was evidencing. He was evidencing that, for him, the only value that black men had in his world was on the court where they made him money and he did not otherwise want to have them in his space unless they were doing exactly that, unless they were performing and creating value for him. Other than that, don’t bring them into my space.”

Sterling was a brilliant personal injury lawyer in his day, and he loved a good fight. He knew how to win them too. Los Angeles is filled with people who came out on the wrong side of a legal confrontation or real estate negotiation with Sterling.

Then he was a real estate shark, a wizard at assessing a property’s value just by knowing its location and specifications.

But his players were never his property. And maybe he learned that when they stood up to him and demanded he sell his team.

“It was a stand for respect,” Griffin said. “At the end of the day, that’s what this is all about. It’s respect for humankind. That was just a somewhat small incident that was able to ignite a whole bigger thing and to bring understanding about this.

“I always go back to the thought that it takes a very educated and thoughtful person to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.”

Donald Sterling was never able to entertain or accept the thought that he needed his players, more than they needed him.

He says it, over and over in the tapes with Stiviano.

“I support them, and give them food and clothes and cars and houses,” Sterling said. “Who gives it to them? Does someone else give it to them? Who makes the game?

“Do I make the game, or do they make the game?”

After Sterling’s reckoning, the answer is clear: The players make the game.

“We’re going to have another [reckoning], and another one,” Rivers said. “And we’re going to keep getting better, but this was important. This was a group of guys that stood up, a league that stood up against something, a commissioner that stood up, coach stood up, players stood up. It was sensational.

“At the end of the day, it was a beautiful moment for our league.”