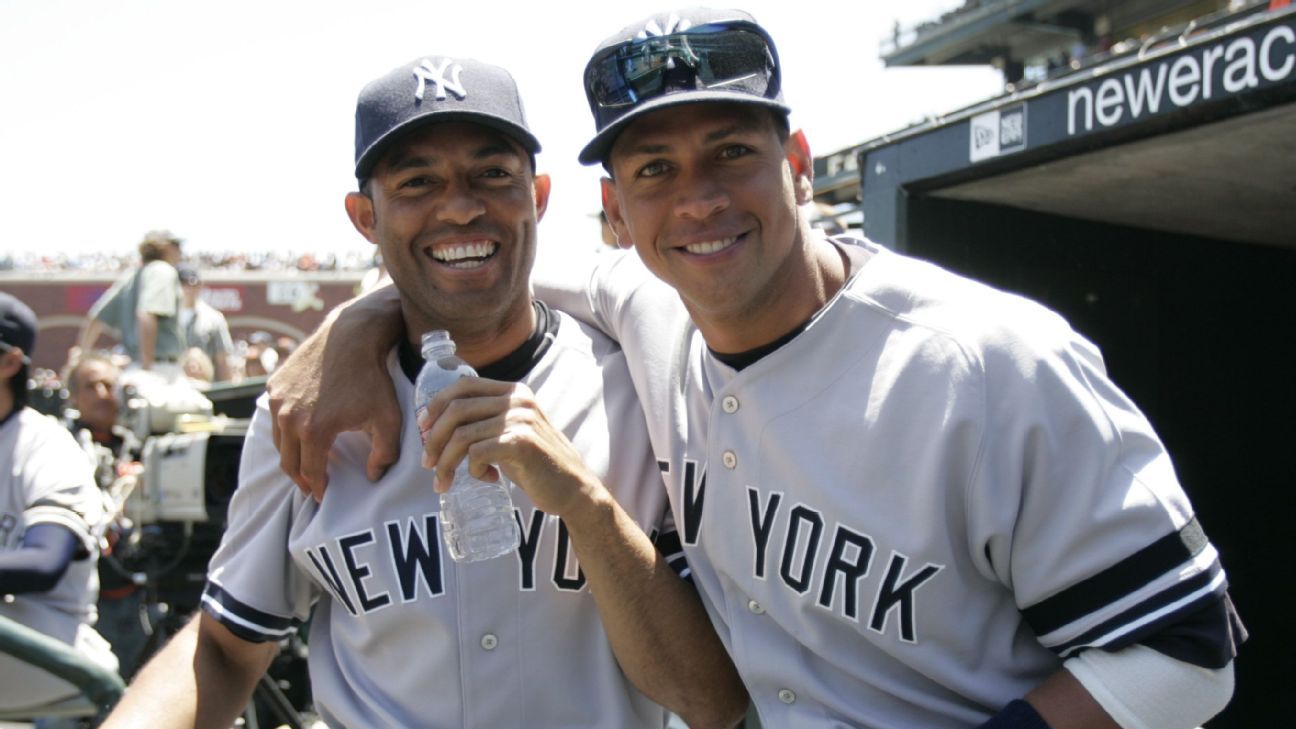

Editor’s note: Alex Rodriguez has a unique relationship with the four players voted into the 2019 Hall of Fame class. He was teammates with three of them (Mariano Rivera, Edgar Martinez and Mike Mussina) and played against Roy Halladay throughout their careers. In the days leading up to their enshrinement in Cooperstown, A-Rod shares the stories of those stars — as teammates, competitors and friends — in his own words.

Mariano Rivera will be inducted into the Hall of Fame on Sunday, the greatest relief pitcher ever, the first unanimous selection. What fans will always remember about him was how unflappable he was on the mound, how stoic, in victory or in those rare moments of defeat.

But the Mo I know is fully capable of bluntly chewing out somebody who needed it. Like me.

One of the worst places on earth to be was in the Yankees clubhouse, in innings one through five, if we happened to be losing or playing poorly, because that’s where Mariano would be, watching everything. As part of his routine, he’d remain in the clubhouse in the early part of the game, preparing to pitch in the later innings, and if we fell behind early and I would walk back to my locker during our turn at-bat, he would be all over me. “What were you thinking, swinging at that pitch over your head?” he’d demand. Or, “What kind of a play was that? Get back out there, you moron.”

He quoted George Steinbrenner a lot, and in our clubhouse, it was like he was the embodiment of what Steinbrenner demanded from the Yankees, in comportment and style. He remembered everything he learned from George and Don Mattingly, and had so much Yankee pride. He was always perfectly shaved — I can’t remember seeing a 5 o’clock shadow on him, ever — and on every road trip, his tie was knotted tightly, perfectly, like he was a drill sergeant.

When I was with the Mariners and didn’t really know him, Edgar Martinez and I viewed him with great respect for how he went about his business, how elegant and classy he was on the mound. He never tried to embarrass you as a hitter, or show you up. Watching him from across the field, there was always a sense of mystery there, and you’d almost think he was shy and timid because of how emotionless he was on the mound. That impression was reinforced by my interaction with him in the American League clubhouse in All-Star Games, because he said so little, barely making eye contact.

But what I learned after I joined the Yankees was that the reason why he kept his distance at All-Star Games was because he was so competitive — he didn’t want to get too close to players he expected to beat — and perhaps the two words in the language that least applied to him were timid and shy. He became an integral part of my baseball world, but also one of the greatest friends of my lifetime.

“One of the worst places on earth to be was in the Yankees clubhouse, in innings one through five, if we happened to be losing or playing poorly, because that’s where Mariano would be, watching everything … if we fell behind early and I would walk back to my locker during our turn at-bat, he would be all over me. ‘What were you thinking, swinging at that pitch over your head?’ he’d demand. Or, ‘What kind of a play was that? Get back out there, you moron.'”

Alex Rodriguez on Mariano Rivera

I don’t think people realize what a phenomenal athlete he was. Late in our careers, there was testing done at the Yankees’ spring training facility, and Mariano had the highest vertical leap of any player there — 35 inches. He could jump like a rabbit, with the flexibility of a gymnast. When he was in his early 40s, he could still drop down into a split. Joe Torre would always say that Mariano was the best center fielder on the team, because of how much ground he covered running balls down in batting practice, and at that time, we had a Gold Glover in Bernie Williams.

Everybody knew what he was going to throw — a cutter — and yet they couldn’t hit it because of that late movement. He has long fingers, like Pedro Martinez, and flexibility in his wrists, and I think that gave him almost like a buggy-whip action when he released the ball. But he also had incredible extension when he released the ball, striding out, and I think that contributed to the late life on this pitch that nobody could hit. I was always fascinated by how smooth his delivery was, how explosive. Science shows that a hitter can’t track a pitch all the way to home plate, and the dramatic movement on his cutter was in the last eight inches. Hitters couldn’t see it, they couldn’t hit it.

I had some problems throwing from third base after I first joined the Yankees — some yips. It wasn’t a Chuck Knoblauch situation, but it wasn’t great. So he and I started long-tossing together every day, to help me. I would stand on the right-field foul line, and he would back up, drifting back until he got to the 399-foot mark in left-center field. I’d have to run into my throws to even have a chance to get it close to him, and he would mock me by maintaining a pitcher’s delivery, like he was throwing out of the stretch — and he would launch the ball so high, like a javelin, and it would go so far up. It would never come down, it seemed. And then it would drop right into my glove.

About 80 percent of our conversations were in Spanish. When Mariano would throw his last warm-up pitch, I’d always be the infielder to flip it to him, as the third baseman, and I’d cajole him in Spanish, calling him muerto — Let’s go, scrub.

I’d say to him, “Mo, if you had my balls, you’d have 800 saves.”

And he’d retort, “If you had my balls, you’d have 1,000 home runs.” After Mariano retired and I played out the last years of my career, he’d joke that he was going to Federal Express — to mail me his testicles, so that I would have some.

He always wanted to teach, and like a pastor, he’s always got a Bible, but he never overdid it; he’s great about messaging. He wanted me to do things right, and look out for me, encouraging me to attend the Sunday morning services they have at ballparks, and on some Sundays, I’d be exhausted and beg off. He’d get annoyed, punishing me with silence for a day. I hated letting him down.

In the worst of my trouble with the commissioner’s office, Mariano called me all the time. He got on a plane, flew down to Miami to see me and was very direct: “What the hell are you doing?” He never supported the crap that I did. He is filled with conviction, and was always true north.

I made a lot of mistakes and he called me out directly, looking me in the eye and chastising me. But he never did it in a way that made me feel like he looked down on me; he made me feel that it was possible that I could find my way through, if I made better choices. Mariano never turned his back on me, and he gave me hope.

Eventually, I owned my mistakes. Mariano texted and asked, “Why weren’t you doing this your whole career?” After I returned to the Yankees in spring training of 2015, Mariano arrived as a guest instructor and picked me apart good-naturedly, as old friends will do.

Then he looked at me and said, “You’re doing really well.”

I get goosebumps thinking about those words and how much they meant in that moment, coming from somebody with as much depth and character as Mariano Rivera.

I’ve never really been into music, but it felt like I was standing in the wing of a concert stage when Mariano came into a game at Yankee Stadium, with “Enter Sandman” thumping out of the speakers and the roar of the crowd in response, and Mo jogging in for the final act, head down. I’d tell myself how lucky I was to be there to see him, the greatest pitching weapon in baseball history.