BOSTON — These Eastern Conference semifinals between the Boston Celtics and Milwaukee Bucks would be the first test of whether the Bucks were real. Skeptics wondered whether a regular-season juggernaut that had never won a playoff series could rise to the occasion against a Boston team that came within a game of the Finals last year — and reintegrated a superstar point guard who hit one of the greatest clutch shots in NBA history to cinch the 2016 Finals.

Boston’s blowout win in Game 1, 112-90, was catnip for Milwaukee skeptics. The Bucks heard it.

“People say a lot of things,” Bucks guard Eric Bledsoe told ESPN.com between Games 3 and 4 in Boston. “We take it personally. We want to prove them wrong.”

While observers wondered if they might teeter after Game 1, the Bucks kept an even keel. “No one was hanging their heads or mad at each other,” Brook Lopez told ESPN.com.

They watched film together, and realized they had not played with their usual pace and fury. Instead of sprinting to the corners and taking up position behind the wall Boston’s transition defense was building at the foul line, Milwaukee’s shooters had jogged up the floor and fanned lazily out to the wing.

They did not help-and-recover on defense with the usual vigor or timing. Perhaps their first-round sweep of the Detroit Pistons had been too easy, the five-day layoff between series too long.

“I don’t think we were prepared for how fast and intense Game 1 would be,” Bledsoe said. “We were fatigued from the layoff, at least I was.”

They watched the video, owned the failure, and steeled themselves for a borderline must-win. “It was a bad feeling,” Giannis Antetokounmpo told ESPN.com in Boston. “You just got your ass whooped at home by 25. If they got up 2-0, it’s trouble. We just told ourselves, ‘No matter what, no matter how you feel or how you played in Game 1, we have to leave Game 2 with a win.’

“Everybody brought it that night, and ever since.”

Somehow, the Bucks have brewed the right mix of humility and confidence. They are aware they have achieved nothing, but sure they can achieve everything. They have, almost by accident, constructed a team with a perfect pecking order. Everything flows from Antetokounmpo. Middleton supplies wing scoring, Bledsoe elite defense and some off-the-bounce oomph. Lopez is the largest long-range shooting specialist ever.

Aside from some early speed bumps adapting to Mike Budenholzer‘s system, Milwaukee’s locker room has been a placid place. No one complains about touches. They do their work, and go out for big team dinners on the road. It has made for a marked contrast with the on-again, off-again melodrama across the hallway in Boston.

As they surged to the league’s best record, Milwaukee’s players and coaches began to whisper that they felt something special coalescing — something most of them had never felt before in the NBA. They acknowledged that feeling, but also understood how fragile it was.

When Middleton returns home to Charleston, S.C., in the summers to host a camp for kids, the young campers often ask him about his goals — if he wants to win a title, or make All-Star teams. His go-to answer has likely disappointed them: “I just want to win a playoff series.”

They vowed they would not take Detroit for granted, and they destroyed the Pistons with almost alarming efficiency. They respect Boston, and they righted themselves with a blowout of their own in Game 2.

They arrived in Boston, a house of horrors for them last season, determined to take back home-court advantage in Game 3. Once that was done, they smelled blood. “Now,” Middleton said, “let’s get two in a row.”

Their shooters started to race behind Boston’s wall, and into the corners for open transition 3s. They found creative ways to get Antetokounmpo the ball in transition so that he wasn’t just bringing it up the middle of the floor with Al Horford, perhaps the best defender of Antetokounmpo in the whole league, laying in wait. They instructed Antetokounmpo to sometimes sprint ahead of the ball and take outlet passes, and to attack along diagonals where it would be tougher for Horford to find him.

They used more varied screening actions, on and off the ball, to present Boston with bad choices: switch someone other than Horford onto Antetokounmpo, or put yourself into rotations. When Boston switched, Antetokounmpo feasted. No one other than Horford had any chance.

Sometimes, that meant Bledsoe and George Hill screening for Antetokounmpo, or vice versa, a method of targeting Boston’s point guards — including Kyrie Irving, who struggled horribly on defense in Game 3 and then on the other end in a Game 4 brickfest. In Game 3, they got traction with an Antetokounmpo-Lopez pick-and-roll they had almost never used before in the postseason.

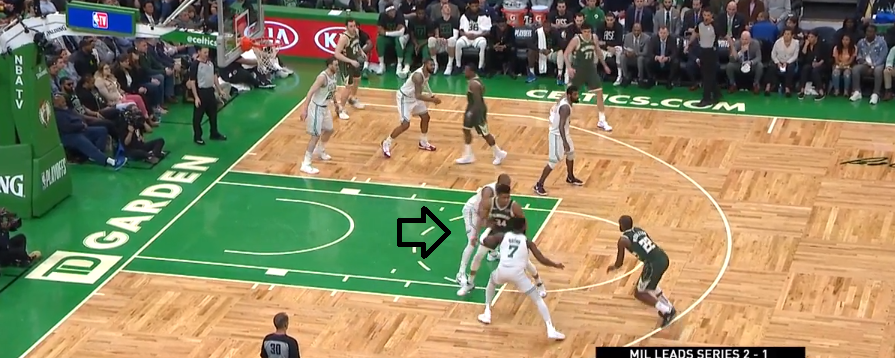

In Game 4, they cleared one side of the floor for the Middleton-Antetokounmpo two-man game:

That setup has Milwaukee’s two best players working in concert, with no defender in normal help position. “It starts with me coming off [the screen] as a threat to shoot,” Middleton said. “And if both defenders jump out at me, Giannis is such a dangerous player, he only needs half a step of space.”

Bledsoe found his attacking groove in the second half, toasting backpedaling defenders one-on-one in semi-transition, and busting into the lane for layups and kickout passes. “Khris was cussing me out after Game 3 for not attacking enough,” Bledsoe told ESPN.com. “He said I was settling. I love him for that.” He punctuated the performance with two emphatic blocks, including a patented chase-down on Irving late in the game.

The real revelation came on the other end. The Bucks since Game 1 have held Boston to just 100.9 points per 100 possessions, way below the league’s worst regular-season offense. Boston clanking open looks, especially in shooting just 9-of-41 from deep in Game 4, helped some. (Irving will rightfully take a lot of heat for his performances in Boston. He took a lot of bad shots. But he also made a lot of good passes — a lot of “make the right play” kickouts — that Boston could not pay off in Game 4.)

0:43

Kyrie Irving says his confidence in his team to win the series is “unwavering” against the Bucks.

Milwaukee began switching more in Game 2, and even dared in Game 3 to switch Lopez onto Irving. Boston wanted to leverage the Irving-Horford two-man game — and other combinations — into easy pick-and-pop looks. Milwaukee’s players thought they could vaporize those looks by switching. During a film session after Game 1, some of the players — Bledsoe was the loudest by all accounts — pushed Budenholzer to let them switch more.

Only Orlando switched less often this season than Milwaukee, per Second Spectrum data. Budenholzer does not like switching. He is a little old school that way. Switching is a form of surrender, or sloth.

But he relented, and it worked. It can be hard for teams to play one way all season, and snap into another style when it really matters. It was not hard for the Bucks because they had developed good, careful defensive habits — competitive habits — over eight months together. They merely had to translate those habits into a different scheme.

They shined in Boston. Without about 11:20 left in regulation of Game 4, Boston ran one of those dreaded Irving-Horford pick-and-rolls. Milwaukee switched, leaving Antetokounmpo on Irving (fine) and Bledsoe on Horford (not fine). Horford rumbled to the block. Bledsoe fronted him. Nikola Mirotic crept behind Horford, and away from Marcus Smart in the left corner, in case of a lob pass. When that pass arrived, Mirotic and Bledsoe swarmed Horford.

Horford kicked to Smart, but Middleton was already rotating there. No dice. Smart drove and kicked it up top to Jayson Tatum, but Middleton had peeled over to Tatum after passing Smart onto Bledsoe. Tatum had to pump fake and dribble inside the arc. The shot clock expired.

“You could tell,” Bledsoe said of that play, “that everybody [on Boston] started dropping their heads.”

After Game 3, Boston’s coaches preached the importance of driving against every Milwaukee closeout — of keeping the machine moving until a great shot appeared. (Stop me if you’ve heard that from Boston before this season.) The players largely followed that edict. They drove-and-dished and drove-and-dished with ferocity, at least until the game felt decided. That well-intentioned effort didn’t always lead anywhere productive. Another Buck would appear, requiring more.

“That’s what Bud has been preaching in film sessions,” Middleton said. “We are long and athletic. Just fly around.”

An under-noticed star of that scramble defense: George Hill, the reclamation project who scorched Boston for 36 combined points over Games 3 and 4. His defense might have been as good as his offense. Hill’s rotations came on time — with the flight of the ball — and he always went to the right place. In two games, he might not have taken one false half-step.

Hill and Pat Connaughton, Milwaukee’s other bench star in Boston, synched up for a series of gorgeous crisscrossing weak-side rotations late in the third quarter that led to one of the game’s defining highlights: Connaughton leaping to reject a Terry Rozier 3-pointer — Rozier is 3-of-18 since Game 2 — leaking out, and cramming on the other end up to put Milwaukee up by eight.

(That was a critical stretch of the game: Milwaukee opening a lead with Antetokounmpo on the bench in foul trouble. That was not a total fluke; Milwaukee had outscored Boston — barely, but still — with Antetokounmpo on the bench over the first three games.)

Milwaukee isn’t done with this series. The Bucks will not overlook Boston, or Game 5. At practice between Games 3 and 4, Antetokounmpo told ESPN the team had “done its job” in winning Game 3 and getting a split. A reporter — this one — replied that Antetokounmpo didn’t seem like the sort who would be satisfied with a split when an opportunity to push Boston to the brink was staring at him. Antetokounmpo is a killer. That’s why he is the likely MVP.

Antetokounmpo smiled. “My job is over,” he said, “when the whole thing is won.”