Editor’s note: The following excerpt from the new book “SprawlBall: A Visual Tour of the New Era of the NBA,” by ESPN NBA analyst Kirk Goldsberry, has been updated and edited for length and clarity.

As the second round of the NBA playoffs kicks into high gear, the most star-studded series features two unprecedented MVPs in James Harden and Stephen Curry. Both players leveraged the power of the 3-point shot more than any superstars in league history.

Consider these factoids:

-

Prior to 2015-16, no NBA player had ever made 300 3-pointers in a single season. That season, Curry sank 402.

-

At age 29, Harden is already the all-time leader in unassisted 3-point makes.

Curry and Harden are the definitive superstars of the moment, and 3-point prowess is their signature weapon. But as the NBA leans more and more into the 3-point era, it leans less and less into everything else. Not everyone is smitten. Just ask Gregg Popovich.

“There’s no basketball anymore, there’s no beauty in it,” Popovich said back in November. “Now you look at a stat sheet after a game and the first thing you look at is the 3s. If you made 3s and the other team didn’t, you win. You don’t even look at the rebounds or the turnovers or how much transition D was involved. You don’t even care.”

Pop is right. Not only has the analytics era of the NBA dramatically reshaped shot selection across the league, but shooting is by far the most important component of winning games. Teams with a higher effective field goal percentage (eFG%) than their opponents won 81 percent of their games during the regular season, and they’re winning 90 percent of them in the playoffs.

When most of us talk about how analytics has changed hoops, we hone in on the dramatic increases in 3-point scoring. But in a zero-sum game, if you’re doing a lot more of one thing, you must be doing less and less of something else. The rapid rises in perimeter shooting necessarily come at the expense of other basketball behaviors. As we continue to be increasingly seduced by the 3, what parts of basketball are we leaving behind?

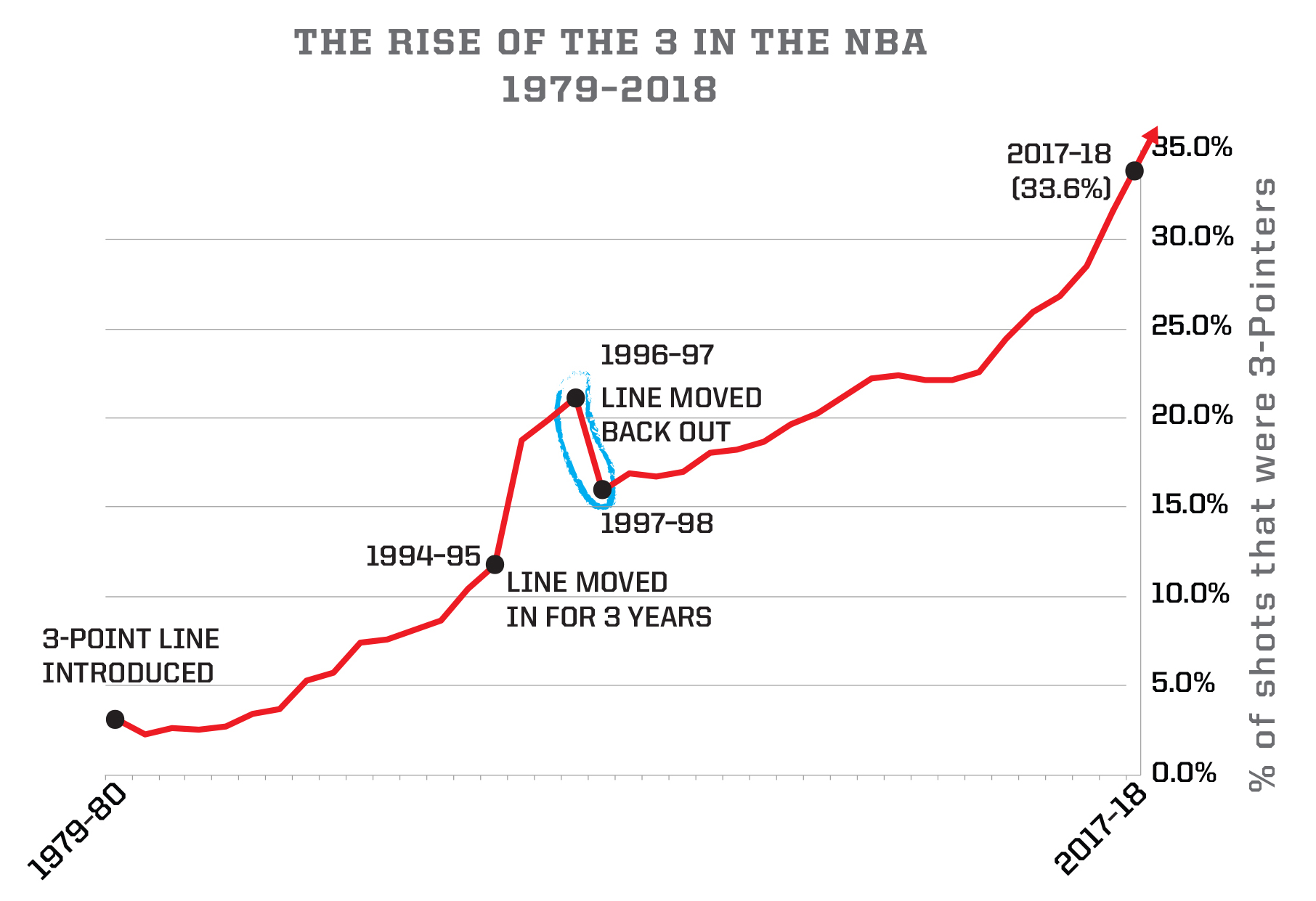

The NBA has now had the 3-point shot for a longer time than it has not. With the exception of a brief three-year window in the 1990s when the league moved it in, the line has remained in the exact same position. In fact, the current configuration of the NBA court has been in place longer than any previous configuration. For many us, 3s are losing their luster. The shooters are too good and too comfortable, and the shots are too common.

Consider this crazy stat: During the 2018- 2019 regular season, NBA shooters made 27,955 3-point shots. That’s more than they made during the entire 1980s (23,871).

Historically, the league has demonstrated an impressive willingness to change its rulebook and its playing surface to keep game play diverse and interesting. In 1947, when the league outlawed the zone defenses that were stagnating flow, one of the main defensive tactics in the sport disappeared.

In 1950, to reduce roughness and deliberate fouling, the league added jump balls after every made free throw that occurred in the last three minutes — as opposed to simply giving possession to the fouling team after the free throw.

In 1951, the so-called Mikan rule drastically changed the appearance of NBA courts by doubling the width of the lane from six feet to 12 feet, primarily to reduce the unprecedented post-up dominance of George Mikan. Thirteen years later, in 1964, the league widened the lane again, to 16 feet, this time to reduce the post-up dominance of Wilt Chamberlain.

Is it time for a Mikan Rule to reduce the dominance of the 3? Let’s explore some ways to change the thing, beyond the simplest adjustment of moving the line back — a logical idea with precedents in college basketball, the WNBA, and even in the NBA itself.

Custom lines

Warning: The following idea has often been ridiculed as the dumbest thing I ever proposed. However, a few people have told me it’s brilliant. I present it again here, and will let you decide for yourself:

What if every team in the NBA could draw the 3-point line wherever they wanted?

Ever since the inception of the sport, basketball courts have been the same shape with equal dimensions no matter what city you played in. This consistency separates the sport from baseball and soccer, which both have different dimensions in different arenas.

When you walk into Fenway Park for the first time, you are greeted by the famed Green Monster, the left-field wall that is one of the most iconic images in baseball. Now imagine the same thing in basketball. What if different NBA teams had different dimensions on their 3-point lines?

For generations, Major League Baseball teams have accounted for park factors as they assemble their rosters. The Red Sox love right-handed power hitters who can take advantage of the Green Monster, and the Yankees love left-handed power hitters who can exploit the short porch in right field at Yankee Stadium. What if basketball teams could do the reverse? What if every season each NBA team delineated its own 3-point line based on the strengths and weaknesses of its roster?

Where would Golden State put its line? What about Houston? You might think that Golden State would put their line closer in to get more 3s; however, their shooters all thrive from deep. Curry, Kevin Durant and Klay Thompson all hit from 25-plus feet with relative ease. By drawing their line at, say, 26 feet, they would emphasize their skills while challenging their opponents to swim in the deep end.

Other teams might choose to move the line closer or to feature asymmetries that keep opponents off-balance.

What if a team didn’t want a 3-point line at all on its home court? This might be the choice of a team with a dominant shot blocker, like Rudy Gobert of the Utah Jazz. Having no 3-point line would force opponents to beat them near the basket rather than from beyond the arc.

That would be the most drastic option. But if dispensing with the 3-point line altogether is too extreme, the league could easily institute some geometric constraints on the delineation of these lines. For example, the line would have to be no closer than 22 feet and no farther away than 30 feet at all locations, or the lines would have to be symmetrical and identical on both ends of the court.

The data-driven line

Here’s an interesting fact: An average NBA field goal attempt is worth almost exactly one point. What a magical analytical convenience! This one-point average is very helpful as we compare and contrast efficiency across teams and players, not to mention shot types.

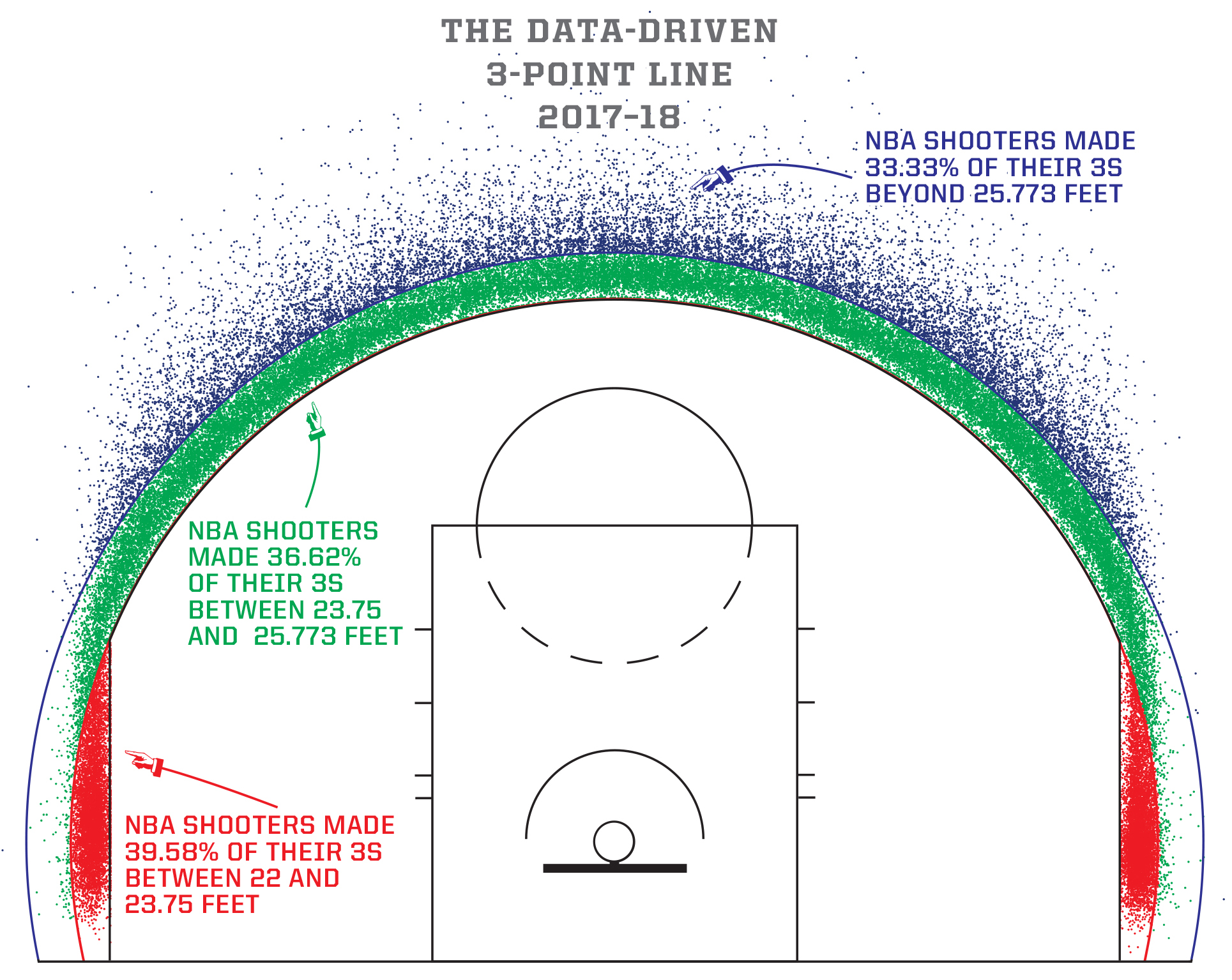

But what if we used that baseline to optimize the placement of the 3-point line? What if the actual shooting and scoring abilities of NBA players informed the layout of the league’s playing surface? For generations, the league has adjusted its playing surface as a way to make sure the game remains as entertaining and competitive as possible. In the so-called Moneyball era, when every team in the league has begun to leverage data to strategize, the league itself has opportunities to do the same thing.

The invention of the 3-point line made 33.33 percent a sort of magical number in NBA analyses. Anyone who can make a third of their 3s can turn 3-point shots into one point on average. It’s the same as making half of your 2s. But as a generation of shooters has warmed up to long-range shooting, NBA shooters are making 36 percent of their triples, and specialists regularly convert over 40 percent of them. That’s the same as making 60 percent of your 2s.

That slight increase in efficiency and the major increase in the population of players who can achieve that efficiency at high-volume levels are two defining drivers of the SprawlBall era.

For individual players, these efficiency upticks may seem small, but at the league level they’re massive. When a whole population of shooters are sinking 36 percent of their 3s, the economic behaviors of shot selection at the population level completely change. There was a time when 3-point shots weren’t the smartest jump shots on the floor for most shooters in the league. That time is gone now. Also, we now have data and analyses capable of mapping out with great precision where NBA shooters make and miss. These maps should inform how and where the league places its 3-point line.

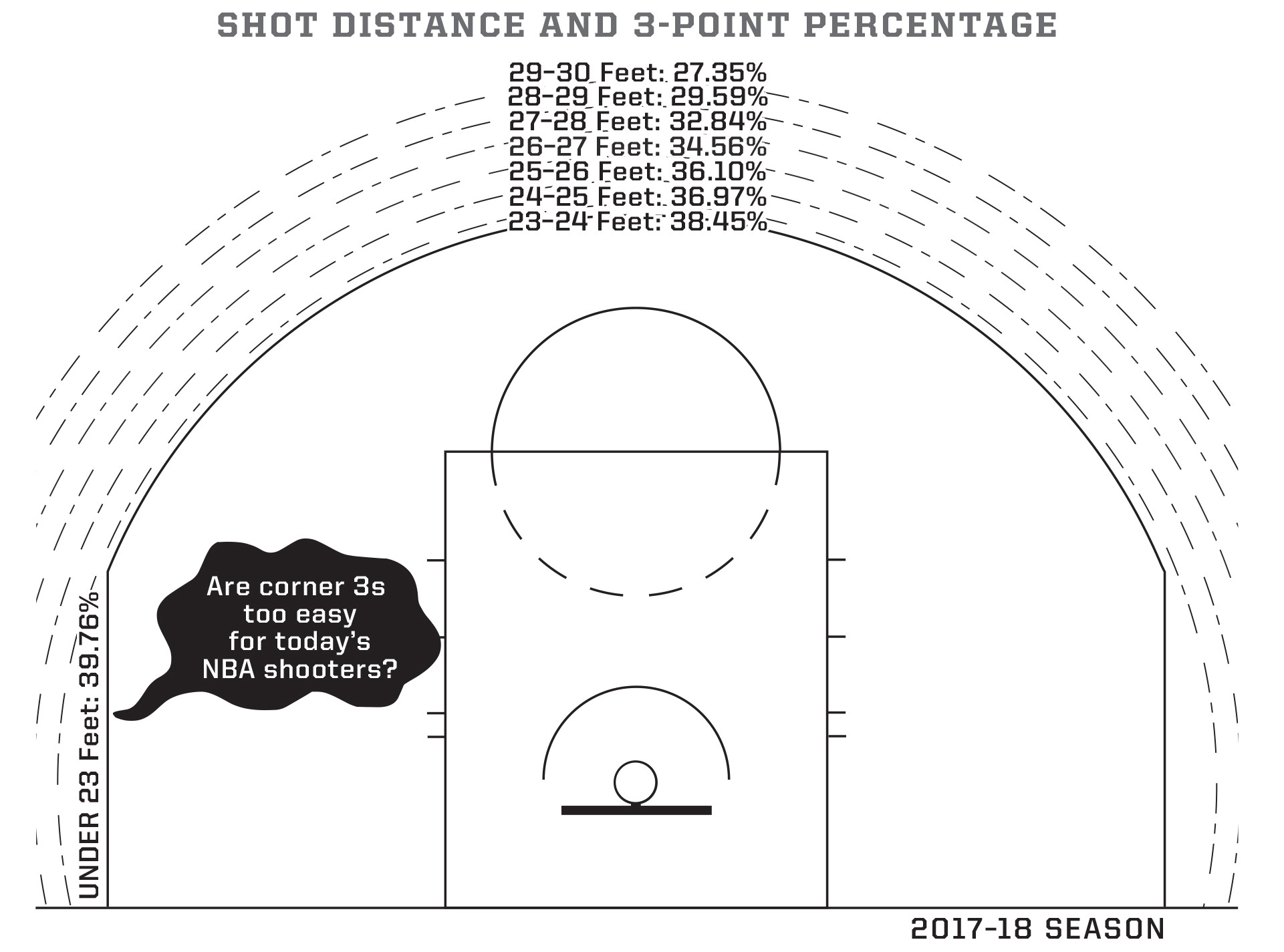

It’s a logical approach based on the guiding principle that shots get harder with distance (duh!) and field goal percentage decreases. Using contemporary shooting data, we can estimate where the line would have to be for the league to convert exactly one third of its 3-point attempts.

Consider the 2017-18 season. By studying league averages at different shot distances, we can hone in on where the league as a whole made about one-third of its 3s. As you can see here, the shortest 3s — those short ones in the corners — went in over 39 percent of the time:

But the graphic doesn’t answer this key question: Where would the line have to be so that the cumulative set of NBA 3-point tries would go in 33.33 percent of the time? That’s a hard question to answer, but by studying the nearly 70,000 non-heave 3-point tries from 2017-18, we can make an estimate. During the 2017-18 season, excluding heaves, NBA shooters made exactly 33.33 percent of their 3s from beyond 25.773 feet, a distance almost exactly two feet beyond the current line.

So why not place the line there?

One cool thing about this approach is that we could refresh it annually. As shooters change, so could the line. Why not conduct this survey and delineation process after every season? Every summer we could look at the previous season’s data and redraw the line based on empirical data. We could forever make 3s worth about one point around the league. Everybody’s 3-point percentage would suffer, but the league’s best shooters would still be valuable. In fact, they might be way more valuable.

As the shot got farther out, players who could hit it 37 percent of the time would remain among the most prized commodities in the league. And make no mistake, Curry would still be among the most valuable players in the NBA. In 2017-18, 36 shooters tried at least 100 3s from beyond 25.773 feet, but only one converted more than 40 percent of them. Curry made a ridiculous 43.6 percent of 172 3s from beyond that hypothetical data-driven line. His ability to be that good from that far out would make him stand out even more than he currently does in the sea of basic bros hitting 40 percent or better from the conventional distance.

As it currently stands, many of the league’s most active spot-up guys are only marginally efficient, and moving the line back two feet would make them even less so. Suddenly the population capable of making 3s efficiently would decline, and the league would have to restore attention to the 2-point areas and the players who could succeed there. Nikola Jokic may have to give up his stretchy ways and bang around the blocks more often. Some 3-point specialists would lose playing time, fadeaways would rise again, and the diversity of shot selection would surge. Some midrangers would be cool again — at least for some players. Many 3-point shots would be dumb shots. And it would all be due to analytics.

Man, Daryl Morey bitten by his own snake.

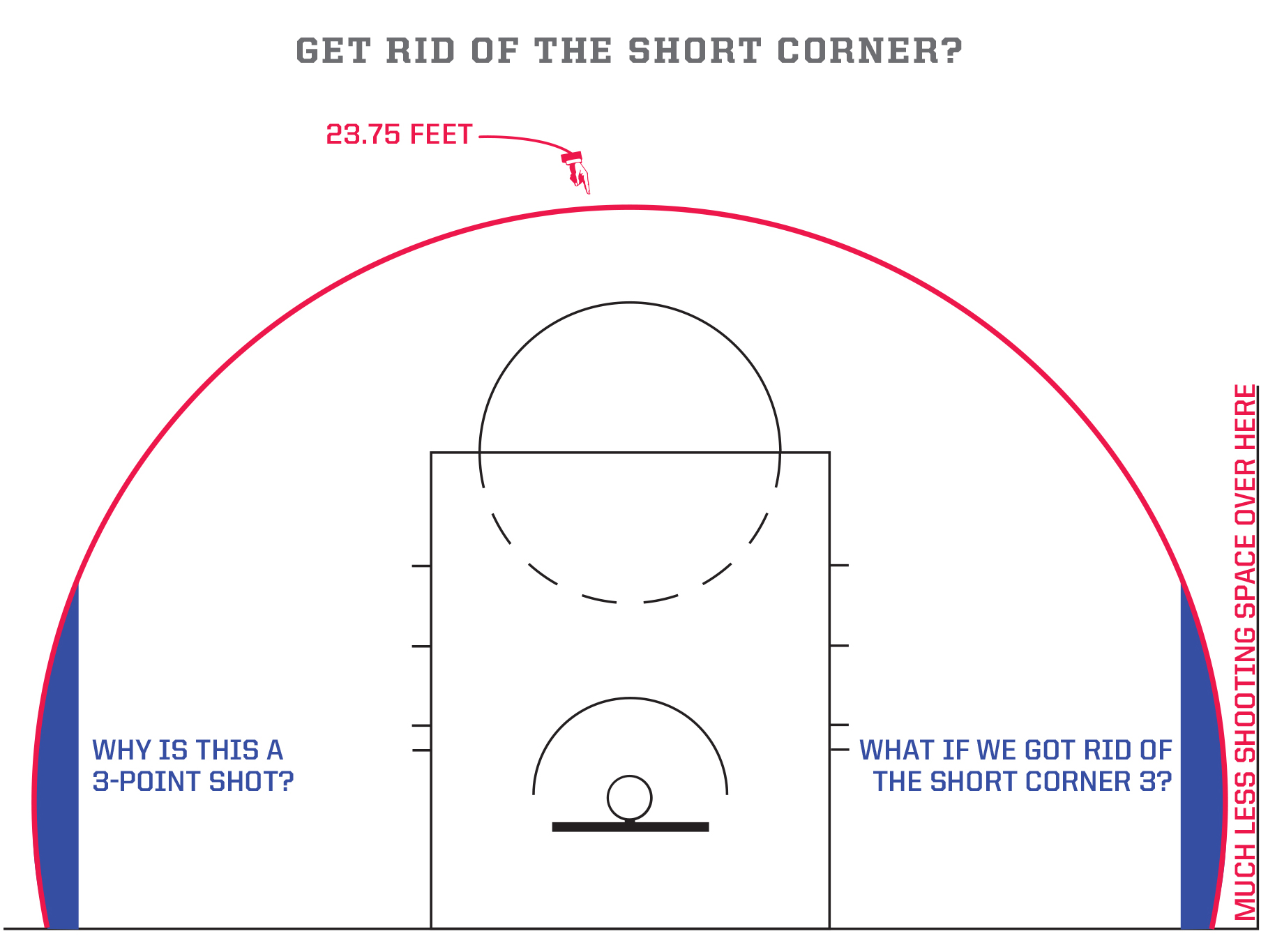

The corner 3

Ray Allen’s incredible 3-point shot in Game 6 of the 2013 NBA Finals was arguably one of the great shots in league history. But here’s the thing: That place where Ray took the shot from — that little spot along the baseline where the 3-point line is straight — is generally regarded as the “smartest jump shot on the floor.”

In fact, that place might actually be the silliest shot on the floor. The corner 3 is based on an analytical loophole, a seemingly minor decision in 1961 that now influences almost every half-court possession in the NBA.

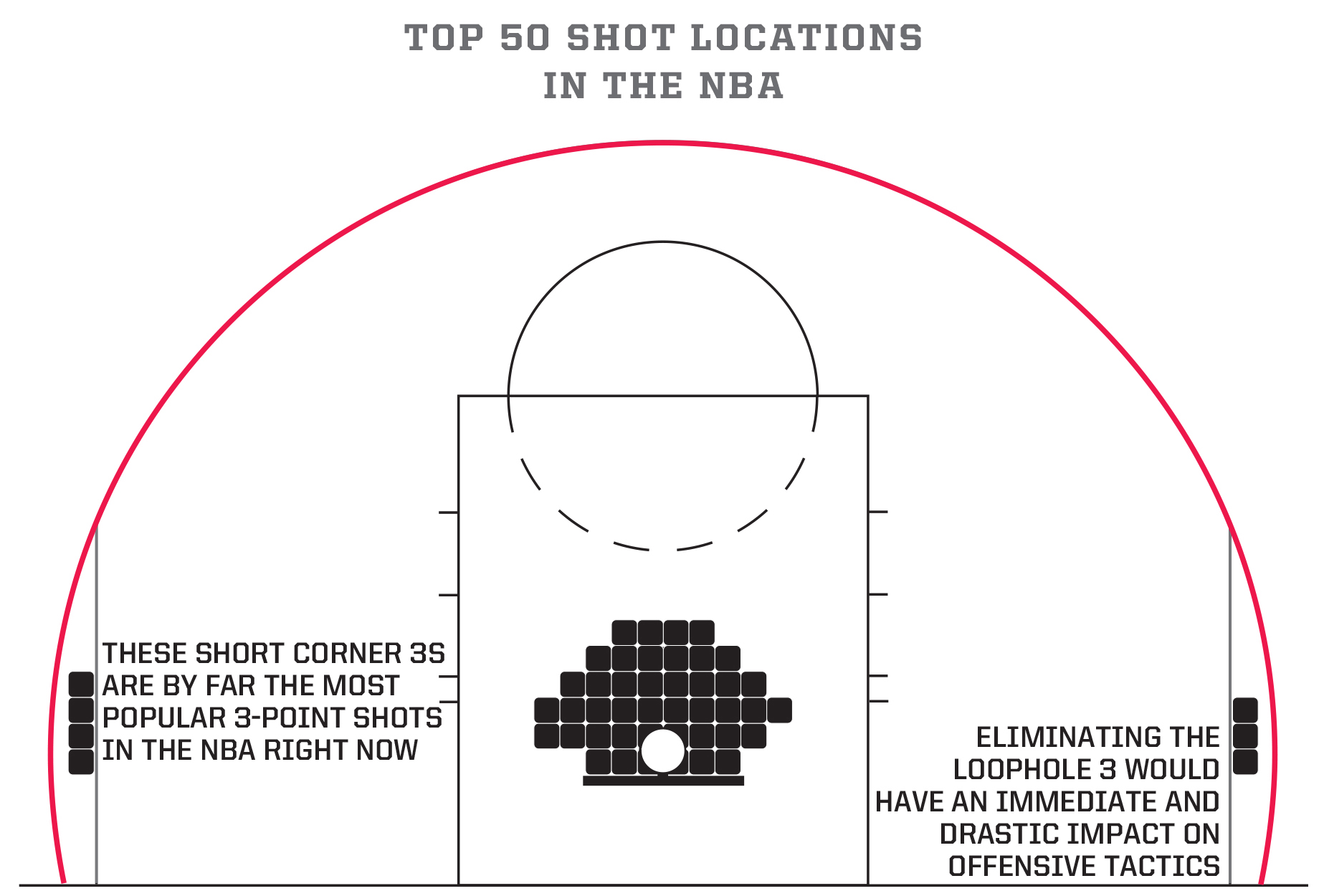

If you watch the game these days, you’ll see almost every team station at least one, often two, players in the remote corners of the offensive chessboard. The rooks in the corners are a signature part of the SprawlBall era. All they do is stand around waiting for shot opportunities that usually don’t come. So most of the time 20 to 40 percent of offensive players in the NBA are just standing around picking dandelions like little league right fielders. But unlike 10-year-old outfielders, who rarely affect the game, even when these rooks don’t get a look, they influence most possessions by stretching out defenses and preventing help defenders from helping. They keep defenses honest, and they accomplish all of this by standing still.

The stationary rooks in the corners effectively turn many NBA possessions into three-on-three. The cornermen and their defenders are reduced to bit players — unless of course one of the rook’s defenders dares to play help defense on a driving player after a ball screen. In that case, a future corner 3 happens via the drive-and-kick.

But is this interesting? Is it good for the league to place such a high value on two stationary shooting specialists camping out in the corners? Maybe, who knows. But one thing is for sure: Outside of dunks and layups, rooks in the corners are yielding the cheapest points on the chessboard, and the numbers leave little doubt that the league is now chock-full of guys who can drain these shots at such high rates that teams would be crazy not to station them every time down the floor. Moreover, the ability to make that shot is now a prerequisite for almost every off-ball player in the NBA. But does anyone go to NBA arenas to watch these guys stand still in the corners?

One simple way to bring more movement back into the game and breathe more life into the 2-point area is to make it a little harder on these loitering bros along the baseline. Drawing a consistent 23.75-foot 3-point boundary wouldn’t completely eliminate baseline triples, but it would get rid of the loophole 3 — the corner triple with a shot distance of between 22 and 23.75 feet.

Loophole 3s not only account for a vast majority of all corner tries, but they’re also the league’s favorite 3-point shooting location by a landslide:

So what would happen if we eliminated the loophole 3?

1. By shrinking the spot-up habitat for corner-3 shooters, we’d make their lives harder and their shots longer. Womp, womp. In turn, that would disincentivize loitering. A consistent 23.75-foot arc would easily fit within the current court. However, it wouldn’t leave much room for spotting up. These tall fellas with big feet would have to slide up or down along the arc before they could find enough space to comfortably spot up, and even then they’d need more balance, more skill, and better offensive timing to generate corner 3s. This simple change could make the game more exciting and the NBA’s shot economy more fair.

2. The most annoying side effect might be a lot more foot-on-the-line moments. This would mean more tedious reviews, which nobody would like. Incidentally, we could also widen the court from 50 to, say, 54 feet, but that would cause major nightmares for every arena manager in the league and force them to reconfigure their entire seating plan.

3. We would see a slight reduction in shooting efficiency from the corner.

4. We would incentivize other kinds of behavior on the offensive end. Fewer rooks, more bishops, knights, etc. How do we create the perfect blend of perimeter action, slashing drives, post-up actions, and fast breaks? That’s a hard question, but one way to reduce loitering on the perimeter is to enact the same rules the league has applied to interior players. For instance, what if we simply added the three-second rule to the corner-3 zone? We could encourage movement on the perimeter and discourage all that standing around.

Allow goaltending on 3s

Many of the NBA’s first major rule changes were aimed directly at Mikan. Defensive goaltending was added in the 1950s to prevent Mikan from blocking shots right before they went into the hoop. Prior to Mikan, goaltending wasn’t an issue, in part because no players could do it. But Mikan could do it, he did do it, and he quickly became the most ferocious defender the NBA had ever seen because of that ability. So the NBA outlawed it, and perhaps no rule change in the history of the game has done more to devalue big men.

What if we revisited that rule change and let defenders block 3-point shots on their way down?

This may sound crazy — and it might be — but goaltending was legal before it wasn’t. And speaking of crazy, so was adding a freaking 3-point shot, which was yet another way the league intentionally devalued big men. By allowing goaltending on 3s but not on 2s, we would breathe some life back into the center position and into the 2-point area.

It would be just like Kevin Garnett swatting those after-the-whistle jumpers, but in regulation. Every time a shooter got ready to release a 3, there would be a flurry of activity near the basket as offensive guys and defenders toiled not just for rebounding position but also for shot-blocking position. Suddenly open 3s would be much harder to come by.

Offensive bigs would have to position themselves to box out potential shot blockers. Catch-and-shoot specialists would have one more thing to worry about before they fired off a jumper. It would be exciting, and it would make catch-and-shoot specialists a lot less dominant than they are now.

Just as Tom Brady has to worry about a lineman deflecting passes at the line of scrimmage and free safeties intercepting them downfield, 3-point goaltending would place a similar onus on Eric Gordon and immediately bring back the relevance of height and athleticism in the NBA.

But would those 3-point blocks be too easy? Some rules would have to apply, such as not being able to simply put your arm through the rim and block every shot that comes near it. Still, if the league found a decent way to sanction goaltending, how many 3s would get swatted? Ten percent? Thirty-three percent? Seventy-five percent? It’s hard to say. Maybe we could pilot the idea in the G League to get the bugs out, but it’s clear that such a change would add a lot of risk to every potential 3-point attempt.

In today’s NBA, catch-and-shoot guys are among the most potent offensive threats on the floor, despite the fact that their signature play is arguably the least risky way to score. As revolutionary as 3-point shooting may seem, from a basic economics perspective, it’s actually very conservative. But if goaltending were allowed, these guys would feel real pressure and have tougher decisions to make. Suddenly they’d have to gauge whether the downward arc of their ball could beat the bigs in a race to the rim.

You could imagine an incredulous Jeff Van Gundy: “What was Gordon thinking? He shot that ball even though Gobert was clearly in the basket area!”

Not only would shooters have tougher decisions on their hands, but the value of athletic centers like Clint Capela and Gobert would return. Smallball wouldn’t make as much sense, and jump shooters wouldn’t be so potent. The game could float back above the rim.

Illustrations by Aaron Dana. Excerpted from SPRAWLBALL: A Visual Tour of the New Era of the NBA by Kirk Goldsberry. Copyright © 2019 by Kirk Goldsberry. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.