Vlade Divac knew he wanted De’Aaron Fox after watching him light up UCLA — and Lonzo Ball — for 39 points in the Sweet 16 in 2017.

Six weeks later, Brandon Williams, now the Sacramento Kings‘ assistant general manager, was part of a Philadelphia 76ers contingent interviewing Fox at the NBA’s draft combine. Someone asked Fox if he had taken special pleasure in outdueling Ball.

Fox gave the polite answer, they recall: Every game mattered. But he sensed the Sixers’ brass might enjoy the real response. “But yeah,” he continued. “That s— was personal.” Everyone loved it.

“It wasn’t necessarily because it was Lonzo,” Fox clarifies today. “It was that he was one of the only NBA-level point guards we played. I didn’t get to play Dennis [Smith Jr.] or Markelle [Fultz].”

Sacramento jumped from eighth to third in the lottery, then back down to fifth after Philadelphia exercised swap rights — remnants of a disastrous trade that will rob the Kings of their first-round pick this season. They invited Fox to Sacramento for a private workout. They wanted to make sure he was more than speed.

Dave Joerger, the Kings’ head coach, had staffers blindfold Fox with medical wrap. They asked Fox to dribble the length of the court at top speed and execute dribble moves when Joerger barked them out: Crossover! Between the legs! Behind the back!

“I wanted to challenge him,” Joerger says. “It was fun. He was just magnetic in his personality.”

“I think I ended up over there,” Fox says, laughing and pointing to the wall lining a practice court in New York.

The blindfold came off. The Kings had Fox run pick-and-rolls in both directions, and they outfitted volunteers in different-colored pinnies — purple, red, blue. The moment Fox turned the corner on a pick, Joerger would scream out a color. Fox had to pass there instantly.

“I did well,” Fox says.

The skills didn’t translate right away. Fox shot 41 percent as a rookie and averaged just 4.4 assists per game. Sacramento moved up in the lottery again — to No. 2 — and faced a pivotal moment: the chance to reorient their team around Luka Doncic. Rivals sensed the dilemma and made offers for Fox — including a template from the New York Knicks centered around Kristaps Porzingis that would have required Sacramento to either send something beyond Fox or take unwanted Knicks salary (or both), sources say.

The Kings might have been able to leverage Doncic fever by trading down, but they wanted a guaranteed chance at Marvin Bagley III. The pick doubled as a vote of confidence in Fox. They didn’t need another ball handler. They wanted a springy big who could run with perhaps the league’s fastest player.

“I like Luka,” Kings GM Divac says, “but we didn’t want to overload with players who — maybe they don’t have the exact same characteristics, but if you want to develop the guys you have, you have to make sure they have room to develop.”

The Kings have won the Fox side of that bet. He is a stud — driver of the league’s happiest surprise. Bagley has exploded over the past two months; he and Harry Giles III have the outlines of an ultra-modern frontline. Buddy Hield and Bogdan Bogdanovic orbit them as shooters, passers and cutters; Hield has been a borderline All-Star this season. They didn’t give up much — yet — for Harrison Barnes, the tweener forward type Sacramento coveted.

In a league that has become all off-court melodrama, the Kings are a refreshing basketball story — a team of guys who fit well, growing together. There is something vaguely Nuggets-y about their construction, their playing style, and maybe their future.

“We want to build it like Denver,” Joerger says. “We want sustained success so that when we do get in the playoffs — maybe it’s not this year, maybe it’s not next year — we have the opportunity to harvest 50-win seasons for five years.”

Divac has no regrets about calling the post-DeMarcus Cousins Kings “a superteam, just young” in June. “I believe that,” he says. “These kids work hard. They have talent. When you have those things, there’s no way you’re not gonna succeed.”

Divac knows what success would mean for Sacramento. He lived it. So did Peja Stojakovic, another of the team’s three assistant GMs; Bobby Jackson, an assistant coach; and Doug Christie, the new color commentator.

“We talk about it all the time: We have unfinished business,” Divac says. “I don’t need this job. My mission was to make the Kings a contender again.”

The path there is murky. Sacramento does not have the asset trove typical of a team that has lost so much, so long. Missed picks have roster-building ripple effects that linger longer than our memory of whom Sacramento actually drafted with them. Having no first-rounder this June is inexcusable, though the Kings have restocked with second-rounders.

There is a hole between Fox, Bagley and Giles (21, 20 and 20 years old, respectively), and the Barnes/Bogdanovic/Hield cohort — all 26. Willie Cauley-Stein fits there, but his future in Sacramento is unclear as he heads to free agency. He has been awful defensively and blocks both young bigs. If the market goes above the midlevel exception — starting about $9 million per season — the Kings should walk.

Barnes, Hield and Bogdanovic could hit free agency in July 2020; Hield is extension-eligible this summer, and Barnes could decline his $25 million option for next season if the Kings dangle a fat long-term deal. All three could be past their apex by the time the Fox/Bagley/Giles trio enter theirs. Overpaying Barnes, Hield and Bogdanovic — and any long-term deal for Barnes this summer would be an overpay by virtue of that $25 million option — could hamstring the Kings later, when they might have an urgent need for flexibility.

Divac isn’t worried about timeline incongruence.

“I would be if Foxy, Harry and Marvin weren’t better than people think,” he says. “They will be ready earlier. And if they are not, they are still the core. We will surround them with players who will help them get to the next level.”

Those words — “ready earlier” — will be catnip to skeptics banking on Divac and Vivek Ranadive, the team’s avid owner, to overspend on veterans in a fit of irrational win-now exuberance that undoes Sacramento’s future.

But to extend the comparison, several of Denver’s key players — Nikola Jokic, Jamal Murray, Gary Harris — proved ready to win big before they sniffed 25. Of course, the twist that changed Denver’s trajectory was Jokic becoming an MVP candidate. Can any current King get there?

Fox is the best bet, though Bagley — a bouncy face-up scorer who will someday be a gigantic pain as a stretch center — has more of a shot than doubters realize. Fox will make All-Star teams. But there is a big gap between All-Star-level point guard and alpha dog of a title team.

With a couple of exceptions — Stephen Curry, Isiah Thomas — point guards of normal positional size (i.e., not Magic Johnson) have rarely been the best players on championship teams. In that sense, it is fascinating to compare Fox and Jayson Tatum — draft classmates. Fox has been better than Tatum this season, but Tatum, as a big and versatile wing for the Boston Celtics, looks the part of a championship-level franchise player. (We will be revisiting the 2017 draft for a loooooong time.)

Fox made a giant leap in Year 2, but everyone around him is confident he has another coming.

“He’ll be averaging 23, 24, 25 per game soon,” says Chris Gaston, Fox’s trainer and agent.

Sacramento coaches often approach opposing coaches and point guards after games and ask about Fox. A common response, they say: He could shoot more. No one can stay in front of Fox one-on-one in the half court, let alone when he rushes at backpedaling defenders in transition.

Every game, you can spot three or four possessions when Fox forfeits a scoring opportunity:

“People have told me I’m passing up shots,” Fox says. “I can be too passive. But I’m trying to find that balance. I love getting other guys involved.”

Sometimes that mentality results in better shots:

Fox is a smart passer mastering the patterns of the NBA. He and Gaston spent the summer drilling different pick-and-roll scenarios with practice players — “human cones,” Gaston laughs. Only the cones moved on Gaston’s orders and sprung surprises on Fox. “We did crazy stuff,” Gaston says. “I’d triple-team him.”

It was clear right away in Year 2 that Fox had graduated from reacting to manipulating defenses. He understood how the second and third lines of defense would respond to every glance and fake, and he began using that against them. He could change pace and toy with help defenders.

Coaches have dialed back Fox’s film study. He doesn’t need it. He remembers how every opponent has defended him and dissects adjustments as they happen. He can recall specific plays in detail without much prompting.

“If he were a normal second-year point guard, we’d be pulling a lot more film,” says Jason March, an assistant who works closely with Fox. “He is at a different level. He sees plays before they happen. When your point guard can do that in his second year, it’s special.”

March marveled during a summer league game in July when Fox, without any suggestion, called a Kings parent club play on the fly — even though only one other player would know it by name. Fox knew it would work — and why. “I looked around and said, ‘Did he just call that?'” March remembers. “We hadn’t run it in three months. Most guys wipe the playbook slate clean over the summer.”

Fox’s unselfishness inspires teammates to run and cut. It might someday attract free agents. “Guys want to play with him,” Joerger says. If Fox doesn’t become Sacramento’s MVP-level superstar, perhaps he could convince one to join.

That is a long way off. The Kings need to figure out things as basic as their core offensive style and who plays what position. Bagley and Barnes sit at the fulcrum of both debates. Bagley’s playing time opened a well-publicized rift between Joerger and Williams that is still healing, sources say. Such divides have undone more accomplished franchises.

Joerger wants Fox in flight, with shooting around him. The Kings play at the league’s highest pace, and they rank among the three fastest teams — in time between the beginning and end of possessions — on trips that start after makes, misses and turnovers, per Inpredictable.

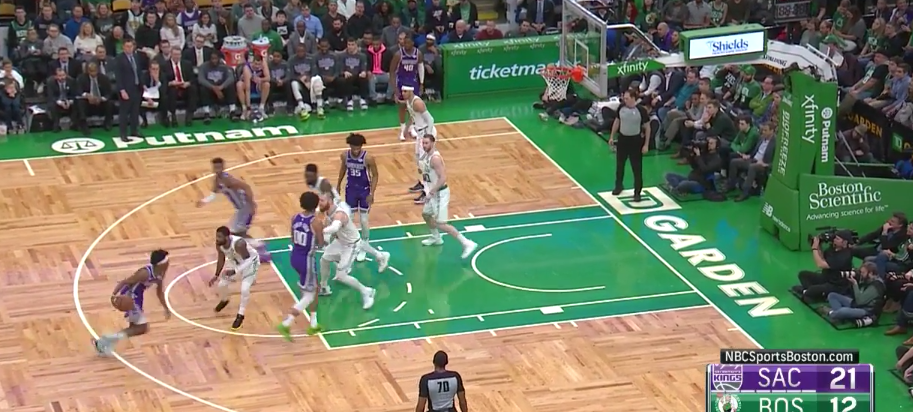

In the half-court — where “fast” isn’t enough — they are searching for an identity. They are tailor-made for a spread pick-and-roll attack when Fox plays with three shooters and only one among Cauley-Stein, Bagley and Giles as rim-runner:

The defense has no good choice. Daring Fox to shoot hasn’t worked. He has drained 37 percent from deep, up from 30 percent last season. The Kings have scored 1.1 points per possession when defenders duck picks against Fox, and Fox shoots or passes to a teammate who lets fly — one of the fattest marks in the league, per Second Spectrum. His pullup from the left elbow is becoming late-game comfort food.

But only six teams set fewer ball screens per game than Sacramento, per Second Spectrum. That is partly by choice. Joerger seems to like an egalitarian system of cuts and screens. Fox himself is a willing cutter and useful off-ball player — essential if the Kings ever land another star.

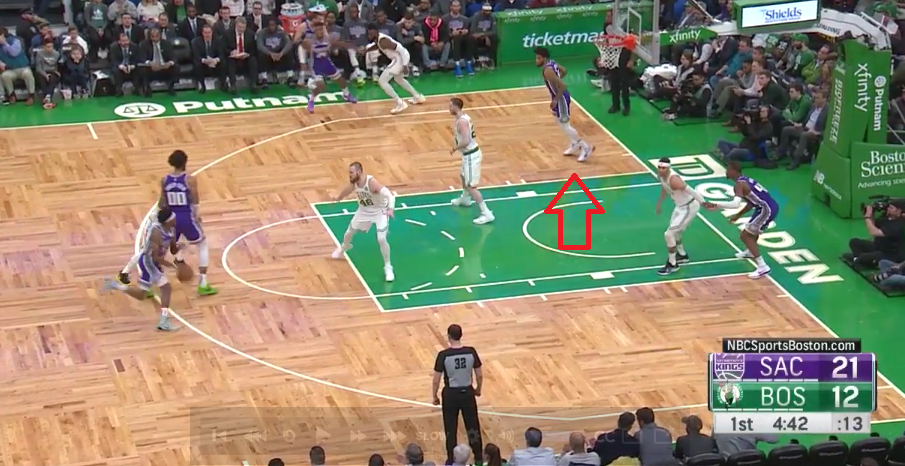

The space around Fox — his room to run a pick-and-roll — shrinks when the Kings play two traditional bigs:

“There are times where our spacing isn’t great, and he can’t go,” Joerger says. “I want as much space around De’Aaron as possible.”

Sacramento has one offense heavier on pick-and-roll for its starters — a group with only one traditional big — and another centered around the elbows for when Bagley and Giles share the floor, Joerger says.

That second system can work. Bagley and Giles are both skilled facing the basket. Giles is a canny passer, Bagley a powerful cutter:

But that setup can reduce Bagley to a floor-spacer role for which he is, for now, ill-suited; defenders ignore him when he chills beyond the arc, far from offensive-rebounding range:

Bagley can scavenge points from the dunker spot while Giles or Cauley-Stein screens up high, but that puts him, and his defender, in Fox’s way:

Nibbling around the elbows also narrows Sacramento’s shot geography. The Kings are 24th in the portion of shots that come from deep. They rank 23rd in half-court offense, per Cleaning The Glass; they are alarmingly dependent on scoring via turnovers — harder to scrounge against playoff teams. (The Kings also have the fifth-lowest turnover rate on offense, giving them the league’s best turnover differential. That could hint at some promise inherent in this team, or end up a bit of fool’s gold.)

This is the theoretical appeal of rushing Bagley into a role as screen-and-dive center and solo big man, defense be damned. Meanwhile, Divac still thinks he can play some small forward. “He can play 3, 4 or 5,” Divac says. “When he develops his shot, he will play some small forward.”

Barnes has spent most of the past two seasons playing power forward. The front office acquired him to fortify the wing. (The Kings talked with the Washington Wizards about a deal for Otto Porter Jr. before pivoting to Barnes, sources say.) Joerger has split the difference by starting Barnes and Nemanja Bjelica at the forward spots. Both can shoot and defend bigs.

Long term, juggling Barnes, Bagley, Giles and another center — Cauley-Stein or a free-agent stopgap — will be tricky. It has been a little awkward meshing Barnes’ ponderous one-on-one game with Fox’s ludicrous speed.

Posting Barnes is a handy crunch-time option, but the Kings can overdo it. The Fox-Barnes pick-and-roll works as a compromise, since both can punish switches — Fox with speed, Barnes with strength:

The Kings should be switch-proof on offense. Fox dusts big guys. Hield rains step-back fire over them. Bagley and Giles bully smaller guys:

The Kings will grow into a good offensive team, regardless of positional quandaries. Crafting a top-eight-ish defense amid those same quandaries is Joerger’s most interesting long-term challenge.

Bagley and Giles have potential as hoppy rim protectors, but it can take big men years to learn the nuances of NBA defense. Giles almost always guards centers, leaving Bagley to struggle chasing stretchy power forwards. “In college, the space you have to cover is much smaller,” Bagley says. “I’m getting the hang of it.”

Sliding Bagley to center more often might be too much, too soon, though such lineups are off to a promising start. He would have to bang with behemoths and serve as Fox’s pick-and-roll bulwark.

Fox is light and prone to mistakes at the point of attack:

Involve Fox and one of the young bigs in screening action, and you get good looks:

Hield and Bogdanovic aren’t moving the needle on defense. (The Hield-Fox backcourt will face some of the same issues Damian Lillard and CJ McCollum — and a lot of slightly undersized guard duos — have navigated before them.) The collective wingspan along the perimeter is wanting. “We’re not tall,” Joerger says. “We have to help and get out to shooters quicker. We help on things that don’t require help. It takes time.”

The result: a ton of enemy 3-pointers and shots at the rim.

Experience and roster continuity will chip away at those problems. Best-case scenario: Giles and Bagley become well-rounded enough on offense to log heavy minutes together without cluttering Fox’s driving lanes — allowing the Kings to pair two switchable shot-blockers. Small-ball skill and big-man size — the endgame of modern basketball.

You see glimpses. Bagley and Giles are nimble. Bagley is shooting 31 percent on 3s — not bad for a rookie big. The Kings have outscored opponents with Bagley and Giles on the floor since Jan. 1, and their best backup unit — Yogi Ferrell, Bogdanovic, Corey Brewer, Giles, Bagley — has been obliterating second units.

Outplaying starters is a different, faraway challenge. Both Bagley and Giles have so much to learn before they could prop up a team defense as the lone big man, or function together against the best teams. Giles can barely shoot outside 13 feet.

But for the first time in forever, the Kings have something sustainable. They are a .500-level team in the Western Conference already, with a culture-setting star in Fox.

He hungers for more, even if star free agents come West and every lottery team improves.

“Next year,” Fox says, “we should definitely make the playoffs. What happened here 10 years ago doesn’t matter. Everyone feels like we can turn this around.”