HE’S A HERO back home. Regardless of how the basketball world might view him these days — as a man disbelieving of his own basketball mortality, as the undersized malcontent who fractured the locker room in Cleveland, as a backup with a questionable future — Isaiah Thomas is adored in Tacoma, Washington. His fandom is spread equally among the people in his city, across races and socioeconomic classes, from the blue-collar neighborhoods downtown to the bucolic boroughs along Puget Sound.

“Isaiah puts us on the map,” said the city’s mayor, Victoria Woodards, from her high-rise office overlooking the downtown docks. “Tacoma represents the good parts of his life, the people and the places who made him who he is.”

He identifies mostly with his old Hilltop neighborhood downtown, where his roots remain deep, and that relationship not only informs the way he sees himself but how he aims to impact the community that shaped him. Three years ago, he gave $80,000 to the local Boys and Girls Club to help build a basketball court that now bears his name. He gave away backpacks to children. He hosted his annual summer basketball tournament and brought in pro players and regional hoops legends, though he physically could not play. The city’s 253 area code is tattooed on his back, above the words “Born & Raised.” His right forearm bears the name of the Fish House Café, on Martin Luther King Jr. Way, where a magazine from his days as a star at the University of Washington is framed and displayed on a wall. His private email address has a reference to his hometown.

With Sacramento, Phoenix, Boston, Cleveland, the Lakers and now Denver, he has carried the soul of Tacoma, a city that, as long as anyone can remember, has been a regional punchline, the “dirty little backyard” to Seattle, 40 miles to the north. Emerald City versus Grit City. Seattle is more cosmopolitan and polished, with its iconic skyline, world-class university and hillsides bursting with million-dollar homes. Seattle has Microsoft and Starbucks and Boeing. Tacoma has Goodwill.

On the northern edge of the Hilltop neighborhood sits a splash of land called Wright Park, where Little Isaiah once played on the blacktop court. Under gray, Pacific Northwest skies, Thomas would hoist shots, his crowd the enormous coliseum maples and giant sequoias rising around him.

Michael Bradley was the supervisor at the People’s Center, on MLK Way, five blocks from the Wright Park court. Thomas often practiced at the center with his father, Keith Thomas, the two staying for hours there, Keith pulling his son to a hoop in the back where they could shoot free throws alone. He taught his son to win battles on the ground, to dictate the game’s speed, to push inside to show he wasn’t afraid. Keith and Isaiah would join pickup games, though the opponents were often three times Isaiah’s age and more than twice his size.

Even then, Thomas’ attitude reflected the swagger that became his calling card in the NBA. “He would go right at you, and he’d let you know about it,” Bradley says. “He always played like he had something to prove.” There’s a story from those days that’s told around the center. Isaiah was without his father one night, a boy hooping with a group of men, destroying defenders, woofing and taunting with each make. After the game, Isaiah called his father and begged for a ride home. Why? Keith asked his boy. The men he’d just beaten were waiting in the parking lot, Isaiah explained. They wanted to whip his ass.

Bradley laughs at the memory. He moves through the old center’s long hallway to the basketball courts, where Bradley coached Thomas as a sixth-grader. There’s video on YouTube from that time, Thomas driving inside and disappearing into a gaggle of defenders. “He’d wiggle his way in,” Bradley remembers. “He was so short, you couldn’t see him.” A moment later, the ball would materialize from the crowd and drop into the hoop.

Isaiah was always his team’s leading scorer, but his coach says there was never an epiphany — no moment when the kid’s basketball future seemed preordained. “There’s no way anyone would have seen him and thought he was going to make it,” Bradley says. Visit enough gyms in this city and meet the people who saw him and coached him back then, and you’ll hear the same thing. Isaiah Thomas was really good, but he didn’t seem special.

Looking back, maybe it should have been clearer. Within the prism of his NBA career, for all the work he has done in his hometown, for all his tattoos commemorating this place, it’s easy to forget: Even his beloved city once doubted him.

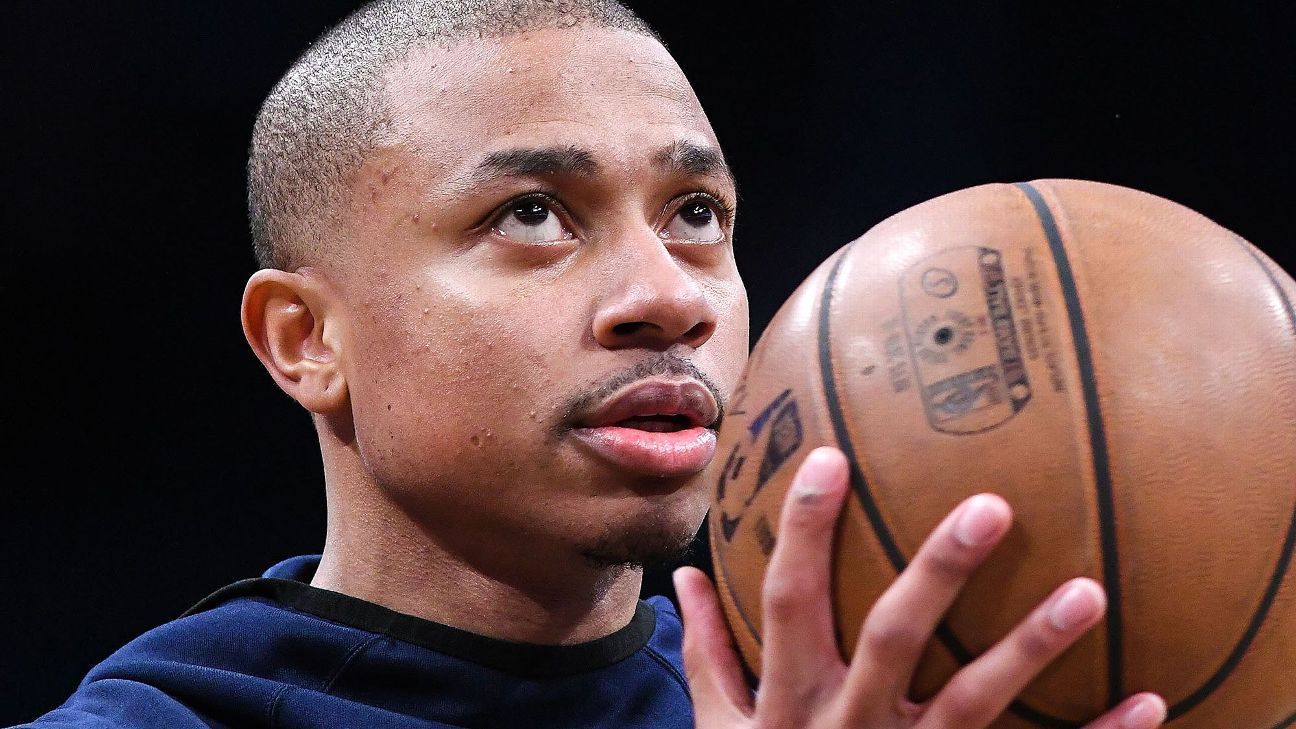

HE LAST PLAYED in an NBA game 11 months ago.

He has watched his Denver teammates from the end of the bench. During timeouts — dressed in a sports coat and tattered designer jeans — he has stood on the periphery of his team’s huddle, a man apart.

The Nuggets are near the top of the Western Conference standings, a surprising run made on the backs of young stars Nikola Jokic and Jamal Murray. IT, meanwhile, has been reduced to a witness, the offensive spark plug that has been sitting on a shelf. Following arthroscopic surgery on his right hip, Thomas has been relegated to the sidelines as he rehabbed the repaired joint, building strength and stability to try to improve his lateral movement and regain his ability to make cuts and drives to the basket. While excitement about his team has grown, the most crucial season of Thomas’ professional career has been moving on without him.

After his injury-riddled 2017-18 season with Cleveland and the Lakers, it has been impossible for Thomas not to sense the weight of this year, to feel the desperate pull of a game that has built him and torn him down too many times to count. This season, on a veterans minimum salary, Thomas was given an opportunity to rebuild his career as the wizened backup point guard in Denver, with an exciting team and a coach he trusts. With the Nuggets, Thomas had imagined proving his legion of doubters wrong, making the league’s 29 other teams regret passing on him in the offseason. If only by sheer will, Thomas would show everyone this season that his 2017 lightning-in-a-bottle ascent had not flickered out.

On Tuesday night, Thomas was upgraded to “questionable” after practicing 5-on-5 earlier in the day. Prior to that, his comeback had been shrouded in silence. Though early speculation had IT playing before Christmas, the holiday had come and gone. Before games, Thomas would wander in and out of the locker room, just one among the herd of suits trailing the team out of the tunnel before tipoff, among the first off the court after the final horn. From his spot on the bench, he had watched Jokic transform into a legitimate MVP candidate. He had seen Murray’s confidence soar. Second-year point guard Monte Morris had solidified his place — once Thomas’ place — as perhaps the team’s most capable reserve. With this surging club rendering his services almost an afterthought, it had been impossible not to wonder whether Thomas’ opportunity disappeared before it began.

“All he’s been through, sometimes you wonder how one person can take so much.”

Suns guard and longtime friend Jamal Crawford

He hinted at the extended layoff before the season’s beginning, lamenting his failed hip rehab the prior season when he declined surgery and instead pushed his battered body onto the court. “I’m taking my sweet time” returning, Thomas said before training camp this past fall. “I want to get as close to 100 percent as possible. We’re not worried about right now. We’re worried about April. We’re worried about the playoffs. However long it takes, I’m only going to go on the court when I can produce at a high level.”

In late March of last year, when Thomas finally underwent arthroscopic surgery on the torn labrum in his right hip, the news was startling but hardly surprising. Bypassing surgery in favor of a rigorous offseason rehabilitation program during the summer of 2017 had shown everyone his desire to play and earn a big-money contract, but it hadn’t repaired his hip. He’d only made it into 32 games with the Cavs and Lakers — posting a career-worst minus-7.3 plus-minus per 100 possessions and shooting just 37.3 percent from the floor. In Thomas’ 14 games with the Cavaliers, the former Eastern Conference champs had been 6-8, surrendering nearly 121 points per game. After a January 2018 trade to the Lakers, opposing coaches saw a limited player, an undersized guard no longer able to break down a defense or slash unencumbered to the basket, the lynchpin to his NBA existence.

Now, on the bench in Denver for the past 56 games, there are no quick answers, only more questions. The Nuggets and the rest of the league now must ask themselves: Who is Isaiah Thomas today? And what remains of the man once considered an MVP candidate as recently as 2017?

The answer lies not just in the past two years, but all the way back to his beginnings.

THOMAS’ LEGEND LIVES quietly in a cul-de-sac in west Tacoma, in a midcentury modern bungalow on Geiger Street, a street with SUVs parked in front of tidy ranches and trees shaped like perfect parabolas.

Ask folks on the street about the junior high school kid who moved here with his father, his stepmother and his sister, and they’ll tell you about the friendly teenager mowing the enormous backyard lawn, or staining the fence, or dribbling a basketball on the driveway, or just sitting out front with his 7-year-old sister, Chyna, a constant presence.

“It looked like a great childhood,” said Curt Curtis, who still lives next door. “You’d see Isaiah out there with his sister tagging along, like he was her protector. You could see in her eyes how much she looked up to her brother.” When Arianna Benitez, her husband Michael, and their young son moved into the Thomases’ house two years ago, a neighbor dropped by with an autographed Isaiah Thomas poster from his University of Washington days. Benitez pinned it to a wall in her son’s bedroom, which she figures is the same room in which Thomas once dreamed of making it to the NBA. “You can feel the pride around the neighborhood,” she says. “People talk about Isaiah all the time.”

Benitez met him once, a year or so ago, when Thomas was working out at the University of Puget Sound, where Benitez’s husband works. Arianna, Michael and Thomas took photos together and chatted about the old neighborhood. As she says this, she points behind her to the wall-to-wall windows off the large dining room, a sweeping view of the Sound and tree-covered hills rising in the distance. “He said he wants to come back here and see this again,” Benitez says. “I told him he’s welcome any time.”

Chyna was killed in a one-car crash north of Tacoma in April 2017. Benitez says she has seen LaNita Thomas, Isaiah’s stepmother, once — when she came over after Chyna’s death to see if anyone might have mailed a condolence card to her family’s old address. Curtis still stays in touch with Isaiah’s dad Keith, who drops by every once in awhile. In February 2018, Keith called Curt. It had been nearly a year since Chyna’s death.

“He was having a bad day, and all I could do was offer some comfort,” Curtis says, his voice lowering. “He was still having difficulty accepting what happened. It’s hard on them, losing her. She was so lovely. I told him I missed her every day, too.”

Last summer, Thomas purchased a gold chain for his father, with a diamond-encircled photograph of Chyna. Thomas got one for himself, too. After games, the medallion often hangs from his neck, just above his heart. Look closely and you’ll see the glass over the photo is smudged with his fingerprints.

CHYNA HAD DIED the day before Boston’s first playoff game in 2017. In the weeks following the tragedy, Thomas performed at an almost unfathomable level, cementing a legacy with a legendary team. He scored 33 points mere hours after her death, leading the Celtics to a come-from-behind, six-game series win over the Bulls. Two weeks later, he scored 53 points in an Eastern Conference semifinals Game 2 victory over the Wizards, a series the Celtics ultimately won in seven games. Seventeen days after that, after tallying just two points in the first half of Game 2 of the Eastern Conference finals against the Cavaliers, Thomas failed to return for the second. His body — more specifically his right hip — had finally broken down.

Sixteen months later, if you had searched for Thomas before the Nuggets’ training camp, you would have found him sitting alone on the trainer’s table, a man lost in the thoughts of his own lost year.

Decked out in his new, blue Denver Nuggets jersey, he pressed his right knee toward the number 0 on his chest, stretching his surgically repaired hip. Across the practice court, beyond a wall of black fabric, his teammates sat at a line of tables, talking to reporters about the upcoming season. There were high hopes for this young team, which had missed the playoffs by a lone game last spring. Leadership and experience, they all agreed, were needed for Denver to make a deep playoff run. Amid the drone of chatter in the distance, Thomas laid his body across the table and blinked into the court’s lights. For the Nuggets, it was a time for renewal and hope. Thomas, though, was haunted by his past.

At 29, he was on a veterans minimum contract he had hoped would deliver more years in the NBA. But if the former All-Star and MVP candidate had been moving anywhere, it was backward: from two contenders in Boston and Cleveland, to a backup with a bum hip with the Lakers, to another backup role on one of the league’s most inexperienced teams — assuming that he was healthy enough to stay on the court.

He’d once been the cornerstone of a surging Celtics franchise, the underdog story made good, the 5-foot-9 guard whose sheer will had transformed him from the very last pick in the 2011 draft into an alpha in a league of alphas. Back then, he had imagined the payday awaiting him in free agency, famously saying the Celtics needed to “bring the Brinks truck out” if they wanted him beyond 2018. After years fighting for respect, Thomas’ place among the pantheon of current NBA stars had finally seemed secure.

Since then, everything in Thomas’ world had been upended — and what wasn’t upended had been destroyed. The death of his sister. The hip injury. The damaging rush back to the court. Nearing his 30th birthday, Thomas was on his seventh team in eight seasons, a man desperately wanting to rebuild himself, a player searching for his place.

“All he’s been through,” says longtime friend and Suns guard Jamal Crawford, “sometimes you wonder how one person can take so much.”

Still, on that day in Denver, after Thomas had stretched out, he stopped to talk. The past is the past, he said. “There’s nothing I can do about that now. I’m focused on what I can do here. I can help this team. I can lead. I will do whatever they need from me. When I’m right, look out.”

When asked about his No. 0, its meaning with his new team, he shrugged. “I’m starting fresh,” he said. “This place, right here, is my new beginning.”

AS THOMAS AND his friends had batted away questions about his injury, those who had studied him noted the subtle changes in his game last season with the Lakers. He was never the quickest player — even when healthy — or a particularly explosive leaper. But Thomas always had the ability to get off his shot, to separate just enough off the bounce, to finish below the rim. Last season, though, Thomas shot only 50.6 percent within three feet of the hoop, the worst rate of his career. For a 5-foot-9 player, the small movements before his cut-and-drive had allowed him to survive in a league with men more than a foot taller. Instead, last season, his physical limitations had only grown more pronounced as he had moved toward the hoop.

Thomas badly wanted to show the Celtics — especially general manager Danny Ainge — they had made a grave mistake when they dumped him for Kyrie Irving late last summer. But in Cleveland and Los Angeles, every day that passed without Thomas’ name on the stat sheet had seemed confirmation that Boston, in fact, had made the right decision.

“He was dealing with a lot on his plate, with the injury and his sister’s death and the trade, and then you throw in the fact he was missing time,” said former Cavs teammate Jeff Green, one of Thomas’ friends. “It has not been a good time for him.”

Tim Manson, Thomas’ former trainer in Washington, stayed in contact with his friend through last year’s confounding season, offering advice on dealing with adversity, making sure Thomas remained “mindful,” assuring him the old 28-points-per-game Isaiah was still in there.

“This has been an extremely humbling experience for him,” Manson said. “He has that Navy SEAL mentality, where he’ll keep going to the point where his life is on the line. There’s no stop in him, which has made all of this harder.”

Eleven days into the start of 2018 free agency — with the LeBron-to-Los-Angeles domino having fallen, everyone from Lance Stephenson to Zach LaVine having signed contracts — the Nuggets signed Thomas to a one-year, $2 million deal. In barely 15 months, Thomas, on his fourth team within that time, went from thinking about a maximum, multiyear contract to a veterans minimum deal.

“You don’t have a right to the cards you believe you should have been dealt,” Thomas posted in an Instagram story the night in September when his contract with the Nuggets was made official. “You have an obligation to play the hell out of the ones you’re holding.”

Five months after signing him, the Nuggets are still hopeful Thomas can be an offensive catalyst off the bench, a sixth man who can play meaningful minutes, an on-court and locker room leader, a veteran presence on a roster with an average age of 24 years old. If anything, it was understood, the opportunity in Denver could give Thomas the bridge he needed to prove his worth to the rest of the league — the chance to price himself out of Denver.

“Isaiah has always been the guy you have to drag off the floor, and everyone yearns for a player like that,” said one Eastern Conference scout. “But teams want to know if he’s going to be 100 percent, or if he’s more like 80 percent. Will he be mobile? Can you rely on him?”

“I don’t know what he wants from this, but we’re all certain he’s motivated,” Nuggets general manager Arturas Karnisovas says. “We want part of the IT that he was two years ago, and I hope we can see snippets of what he once was. We asked ourselves before we signed him: If we have a healthy IT on our hands, what do we get? I think that’s pretty obvious. We just need him healthy.”

Nuggets coach Michael Malone was Thomas’ greatest supporter in Sacramento, where he coached IT from 2011 to 2013.

“Isaiah knows I’m going to look after him,” Malone says now. “I want a guy who can change the game, and he wants to be that player.

“Isaiah has had a tough couple years. A lot of things have been said about him. It’s important for him to play for someone he trusts, who will allow him to be the person and the player he is and not give him any bulls—. I hope he sees there can be a positive ending. If there’s one thing I’ve learned about him, it’s that you never bet against Isaiah.”

DURING THE HARDEST time of his life, when he most needed support, Thomas was reluctant to seek it. He has felt his sister’s loss intensely. He carried his grief privately.

The basketball world got a glimpse of what he was feeling in the days after her death, in April 2017, when teammates and fans reached out in ways that both comforted him and made him uneasy. And while Thomas has been vocal about his return, that he’ll regain his All-Star status, he remains reluctant to talk about the ways Chyna’s death has impacted him.

“I was going through something way bigger than basketball, so basketball was the only thing that can really numb that at that point in time,” he said shortly after undergoing his surgery. “That was the only thing. Basketball was the only thing to keep my mind off something so big.”

Tacoma, too, has felt Thomas’ pain. Any discussion about sports in the city has to include Thomas — his greatest performances, the will to always improve, the injury, the surgery, how the Celtics did him wrong, how LeBron didn’t give him a chance to succeed in Cleveland, how a young star like Denver’s Jokic might benefit from IT’s prodding.

“No matter where he is, or what he’s doing, there will always be a place in Tacoma for Isaiah,” Mayor Woodards says. “We will be there for him, because we need him. Maybe more than ever, he needs us, too.”

Last year, the day before the anniversary of Chyna’s death, Thomas was 1,100 miles away, at Disneyland, with his wife and sons. He could have been forgiven for not wanting to be home, for wanting to be far from prying eyes. When he relives his sister’s death, he says, he rubs that photo above his heart, feels the wave of hurt and longing over and over. Being home just magnifies the agony.

The next day, April 15, Thomas went to the Lakers’ facility in El Segundo. His sons, James and Jaden, ran across the practice court as their father took some shots. He posted photos of his sister on Instagram. “Damn!!!!” he wrote, “1 yr ago today I got the worse news I could ever imagine. I love and miss you so much Chyna!”

That same morning, north of Tacoma — where Thomas once clawed his way to become the star he always knew he was — rain fell as vehicles zipped past a makeshift memorial in the middle of Interstate 5. Behind the concrete barrier, next to the scuffed HOV-lane pole where Chyna died, a red cross was stuck into the ground. On that patch of rain-soaked interstate, everything else receded: the hip, the contract, the game itself, the bitter irony of Isaiah Thomas’ rise and fall in the NBA — from last pick to MVP candidate, the star player who was, but never really was.

A pinwheel spun near a bouquet of pink flowers set in a small white vase. Purple and pink balloons the shapes of stars and a heart lolled in the breeze. Southbound cars approached the memorial, hurtling past, the bobbing balloons getting smaller in the rearview mirrors.

Blink, and they were gone.